The cover headline on the March issue of The Atlantic asks, “Can America Put Itself Back Together?”

Piloting his own single-engine propeller airplane, James Fallows and his wife Deborah spent three years flying around the United States, finding “reinvention and renewal’’ in a diverse array of towns and cities from coast to coast. As they traveled, they posted on-the-scene reports and photographs, which you can find at www.theatlantic.com/americanfutures. And Fallows, who ranks at the top of American long-form magazine writers, produced a summary essay for the magazine, which you can read here: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/03/how-america-is-putting-itself-back-together/426882/

One section, in particular, caught my attention as relevant to North Carolina and especially EdNC’s community of readers. With immigration and ethnic diversity at issue in the contentious presidential campaign, Fallows reports that “people generally saw things as manageable or improving locally, but believed they were falling apart everyplace else.” Then Fallows offers this story of a community and its schools adapting:

“We saw this shift all around the country: older people whiter, younger people darker. One version of what happens next is familiar to anyone who’s ever read a newspaper. Richer, whiter people think that public schools, public places, center cities are no longer for “people like us” and withdraw themselves, their children, and their tax support to the suburbs or private schools. We did see cases of that. But we also saw the opposite.

One example: The little town of Holland, Michigan, got its name because so many Dutch people congregated there. A generation ago, its population was overwhelmingly white, mainly Dutch, and generally affiliated with sects of the conservative Dutch Reformed Church. In high-school graduation photos from the 1970s, nearly all the faces are of blue-eyed blondes.

Since then, Michigan’s surprisingly important agricultural industry, including a large Heinz pickle factory right in downtown Holland, has drawn a substantial Latin American population, and strong Holland-area manufacturing and design companies have drawn immigrants from around the world. By 2005 the public-school population in this famously white town was mainly nonwhite.

In 2010 the superintendent of Holland’s public schools, Brian Davis, who grew up in a white farming family in Michigan, began a campaign to get major new bond funding for the schools. This was in the depth of the financial collapse, in a hard-hit state, in the same election cycle in which the Tea Party made its debut—and Davis was asking a mainly white electorate, most of whom did not have children in the public schools, to refinance the schools. And they did. The new programs and facilities paid for by the bond, according to Davis, helped reverse a decline in public confidence in the schools. “We have children who come from homes with $1 million–plus annual income, and ones who come from homes with incomes under $20,000,” Davis told me in 2013. “Just under 10 percent of them are considered homeless.” He reeled off some of the 20 native languages of his students. “Of course Spanish, but then Japanese, Russian, Tagalog, Korean. We’ve got more Garcias than Vans”—Van being the shorthand for standard Dutch names. “We’re what the future of public education looks like.” This is the reality as we heard it in many other cities.

North Carolina, of course, has its own stories to tell, as well as communities that could emulate Holland. My mind turns to several examples:

Under the leadership of Guilford Schools Superintendent Mo Green, the county has become a “Say Yes to Education’’ community. More than $32 million has been raised from within the community for an endowment fund to provide college financial assistance to graduates of the county’s schools. Green is on the EdNC board of directors, and he has been named the new executive director of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation.

In Forsyth County, the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust plans to invest between $30 million and $40 million over the next decade in an early childhood initiative known as Great Expectations. My colleagues at MDC, the Durham-based nonprofit, are working with the KBR Trust on the activation plan for the initiative, which has the goal of assuring that young children, especially from financially disadvantaged families, are ready to learn upon entering kindergarten.

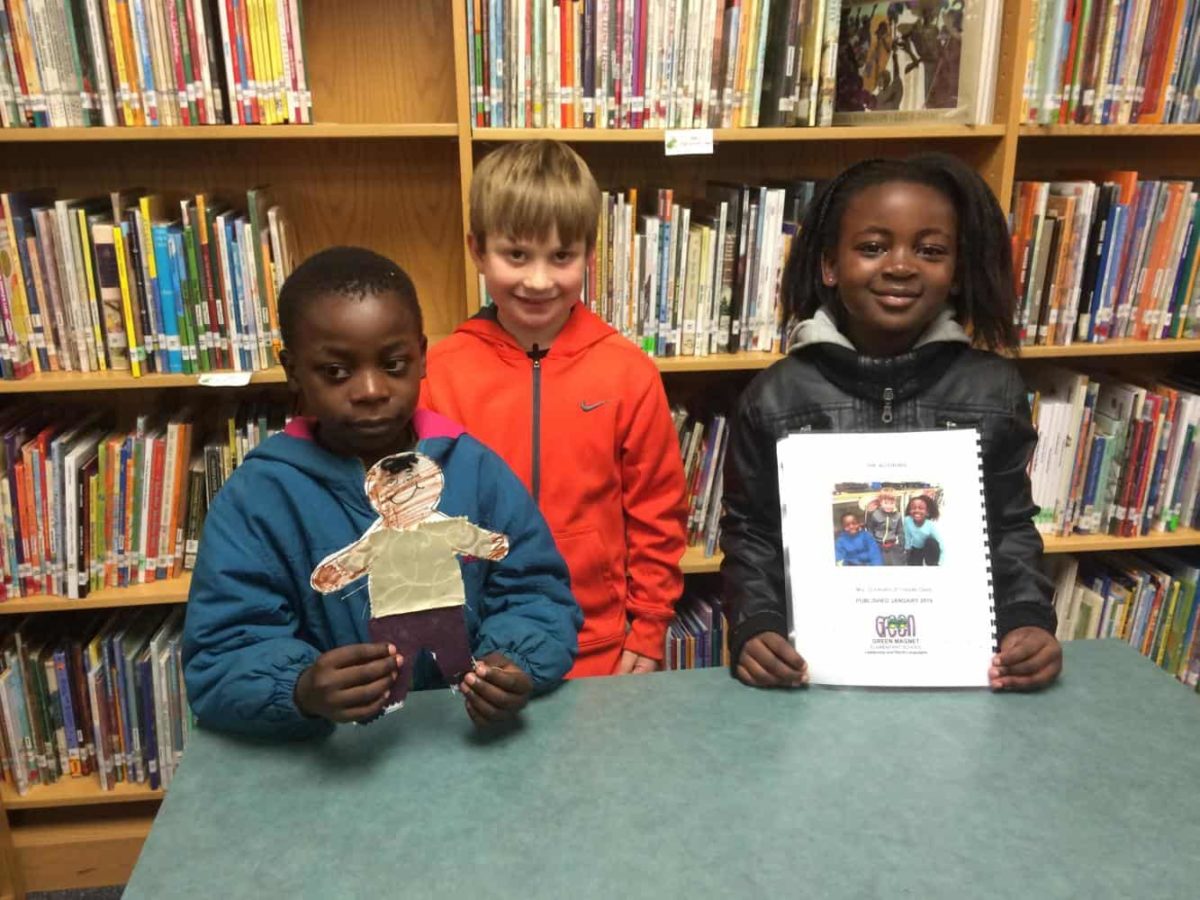

My grandson Jonathan is a 2nd grade student at Green Leadership and World Languages Magnet Elementary in the Wake County Public School System. On its website, Green reports that its “students represent 6 continents, 44 countries, 30 cultures and 15 home languages.” Jonathan has a friend, who recently arrived at the school from Burundi, a land-locked nation in East Africa.

As my daughter Kristen has told me, the student showed up at Green speaking Swahili but no English. By playing soccer and otherwise collaborating with him in the classroom, Jonathan is in effect helping teach the student to speak English. The Wake school system reports that it processed in 2014 more than 2,000 rising kindergarteners who spoke a language other than English.

When school resumes after the summer break, the 500-plus students at Green will return to a brand-new facility on its Six Forks Road campus. Jonathan is among its students taking daily Mandarin classes, while also absorbing the quiet lessons of going to school with students of another race, another culture, another language. Under the state’s A-through-F system, Green got a grade of C – another example of how the grading system doesn’t fully capture what students learn in public education and how public schools can help pull a changing America together.