This week is National School Choice Week, and you’re going to hear a lot of charter school proponents talking about what a great thing choice is for families when it comes to education. Folks who are opposed to unchecked charter expansion will be derisively labeled ‘anti-choice,’ as if their views run counter to American democratic values. But the charter movement in our state is deeply problematic, and it’s important that we have a fact-based conversation about it.

On its face, choice sounds good. We expect it when we go to the store for salad dressing, when we’re looking at books at the library, or when we’re holding the TV remote. What kind of person could possibly be against others having the freedom to make choices when it comes to their children’s education? But what happens when the choices I’m making have a negative impact on those around me? What happens when those choices don’t occur in a vacuum?

Charter schools were originally intended as places of innovation, where educators could develop new approaches in a less regulated setting and collaborate with traditional public schools to improve outcomes for all. In some states, charter schools have been able to stay relatively true to that mission. Not so in North Carolina.

On a systems level, the good that charter schools are able to do is determined 100 percent by the policies that govern them. In North Carolina, charter school policy is a mess, and that mess is leading to some really bad outcomes for our children.

Since the cap on charter schools was lifted by North Carolina’s state legislature in 2012, the number of charter schools in the state has nearly doubled. This year we have 185 charter schools in operation, serving more than 100,000 students across the state (overseen by a staff of eight people). Next year we’ll have 200.

The rapidly expanding charter schools siphon money away from traditional public schools and reduce what services those public schools can offer to students who remain, according to a recent Duke University study. As students leave for charters, they take their share of funding with them — but the school district they leave is still responsible for the fixed costs of services such as transportation, building maintenance, and administration that those funds had supported. Districts are then forced to cut spending in other areas in order to make up the difference. In Durham, where 18 percent of K-12 students attend charter schools, the fiscal burden on traditional public schools is estimated at $500-700 per student. As the number of charters increases, so will that price tag.

While charter schools in some states have been used successfully to improve academic performance for low-income students, in North Carolina they’ve been used predominantly as a vehicle for affluent white folks to opt out of traditional public schools. Trends of racial and economic segregation that were already worrisome in public schools before the cap was lifted have deepened in our charter schools. Now more than two thirds of our charter schools are either +80 percent white or +80 percent students of color. Charter schools are not required to provide transportation or free/reduced-price meals, effectively preventing families that require those services from having access to the best schools.

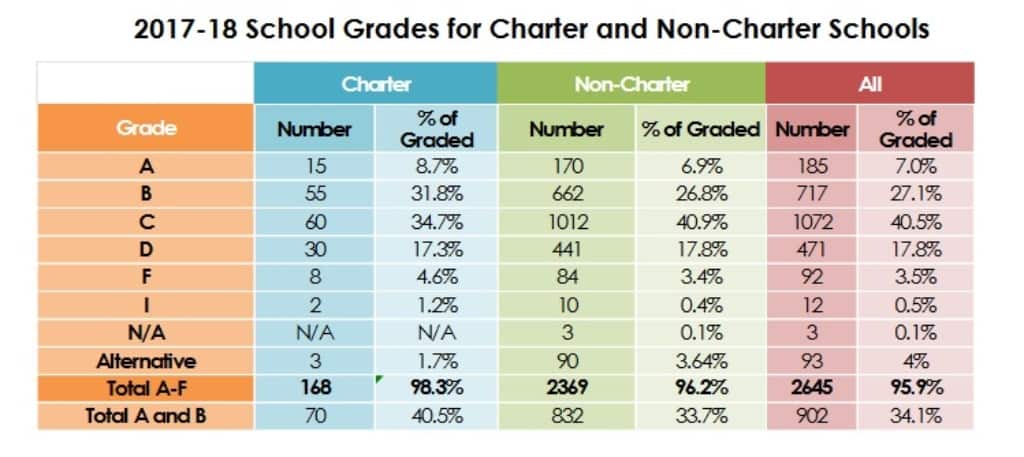

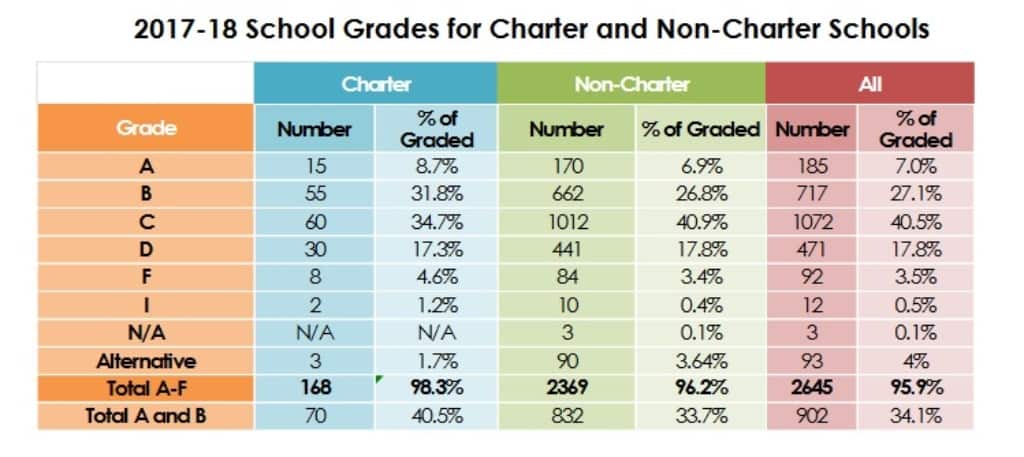

Academic achievement in our hyper-segregated charter schools has played out along socioeconomic lines, just as it often does in traditional public schools. Charter schools that serve primarily low-income North Carolina families have struggled, with percentages of charter schools rating an F according to our school report card system exceeding those of their traditional public school counterparts. On the other end of the spectrum, charter schools earn more As than do traditional public schools. They’re also populated mostly by wealthy white students.

A 2014 study by researchers at UNC-Chapel Hill found that students of color in segregated schools made smaller gains in reading than students of color in more integrated schools. Research also shows that white students don’t experience a decline in those integrated settings. Segregated schools are more likely to have inexperienced teachers, higher teacher turnover and student mobility, and lower quality facilities, while students at more integrated schools see improved academic outcomes, increased educational attainment, and increased likelihood of living and working in diverse settings.

Despite the clear benefits, it’s very rare in North Carolina for charter schools to be intentional about seeking out an integrated population of students. In fact, until 2015, state law didn’t allow charters to use socioeconomic status in their admission lotteries. Even now that they have permission to do so, only three charter schools in the state actively use SES in their admissions process: Charlotte Lab School, Community School of Davidson, and Central Park School in Durham.

I don’t believe that charter schools are inherently bad, and I recognize that there are charter schools doing good work in North Carolina — even a handful that serve low-income students and do so well. However, if our state legislators are really serious about providing families with good choices, they must enact policies that move us in the direction of racial and economic integration and don’t damage traditional public schools. Until that happens, let’s stop pretending that school choice is good for everyone.