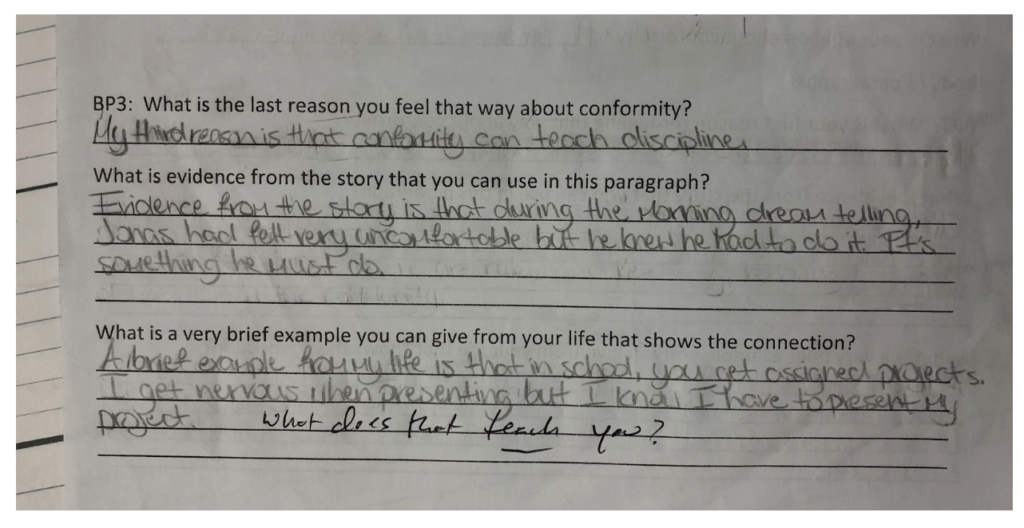

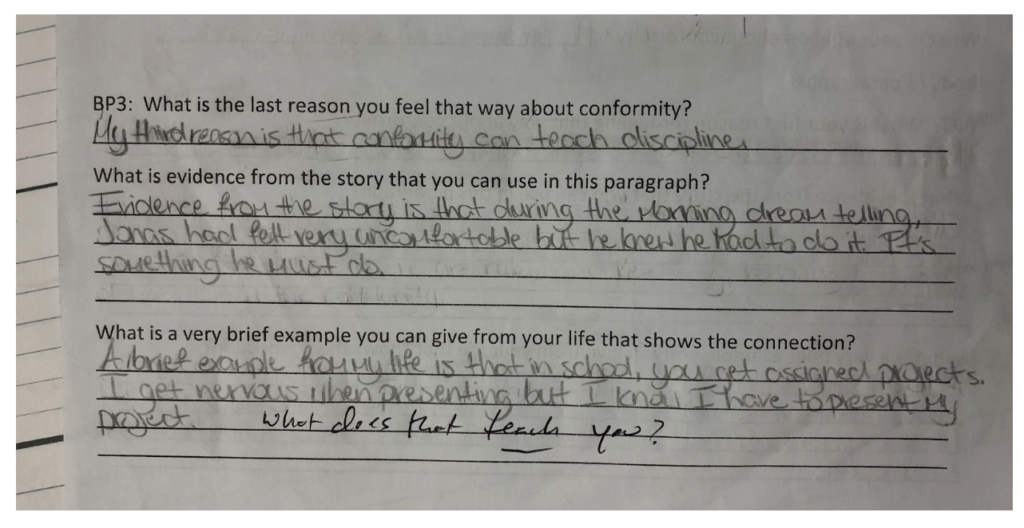

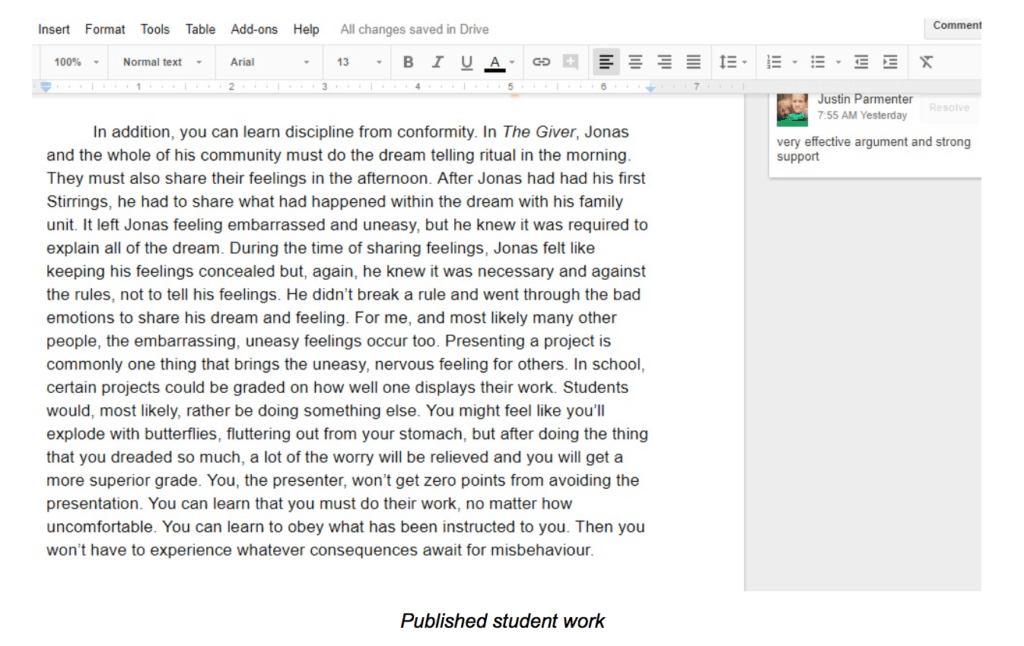

Recently, my 7th grade Language Arts classes spent three weeks working on writing projects. We began with group brainstorming before moving on to individual topic selection, spent a class on outlining, then worked on paragraph writing and supporting claims with effective evidence both from text and from the real world. Finally, we wrapped up the drafting phase with peer editing and careful revision before students ‘published’ their completed essays.

In addition to meeting the goals laid out in our state writing standards, I wanted my students to learn the processes and strategies that lead to effective writing so that they can apply them to writing that they do in any context. Although I firmly believe those are valuable and practical goals, I have to admit that by about the end of week two I was starting to worry whether I was devoting too much time to the project. After all, statewide reading assessments are always around the next corner.

To a degree, worries about pacing have always been part of teaching. English teachers are constantly trying to find the balance between reading, writing, listening and speaking while slogging through an enormous amount of curriculum in a limited amount of time. But the level of fear that teachers experience around balancing curriculum escalated sharply with the boom in standardized testing brought on by No Child Left Behind. The resulting teach-to-the-test culture has led to a marked decline in the quality of our students’ writing.

When the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act was signed into law by President George W Bush in 2002, it optimistically branded itself “An act to close the achievement gap with accountability, flexibility, and choice, so that no child is left behind.” The bill aimed to raise reading and math achievement levels which had been languishing for years.

The speech President Bush gave the day he signed the education reform bill painted a dark, cynical view of an education world in which students are “shuffled through the system” because educators don’t take the time to figure out how to solve their problems. President Bush made it clear that access to billions of federal education dollars would depend on state-level compliance with a testing regimen designed to root out poor teacher performance.

After setting goals that were all but impossible to meet–100 percent of students at grade level proficiency in math and reading by 2014–the act laid out severe penalties for schools that failed to make Adequate Yearly Progress toward those goals. Such schools could be forced to replace low-performing teachers or completely overhaul curricula. In extreme cases they were faced with firing entire staffs or turning over school operations to the state or private companies.

Once NCLB became law, the implications for classroom teachers across the country were clear: The primary focus for each child became their scores on standardized tests in reading and math. At the same time this change in instructional priorities was occurring, there was a shift toward broadcasting the successes and failures of teachers more widely by making their test results publicly available and assigning schools performance scores–both of which stood to impact public perception of educators in a big way.

As the realities of NCLB trickled down to the classroom level, the overwhelming pressure on English teachers to get results on reading tests led to many teachers reducing the amount of instructional time devoted to writing. With money spent on standardized testing ballooning to $1.7 billion a year, states that had been assessing writing on a wide scale in some cases discontinued that practice (in North Carolina, writing assessments were phased out in 2011 because of the expenses associated with scoring them). Writing standards still appeared in each state’s curriculum, but NCLB only mandated that math and reading be tested. And in the education world, unfortunately, what gets tested is often what gets taught.

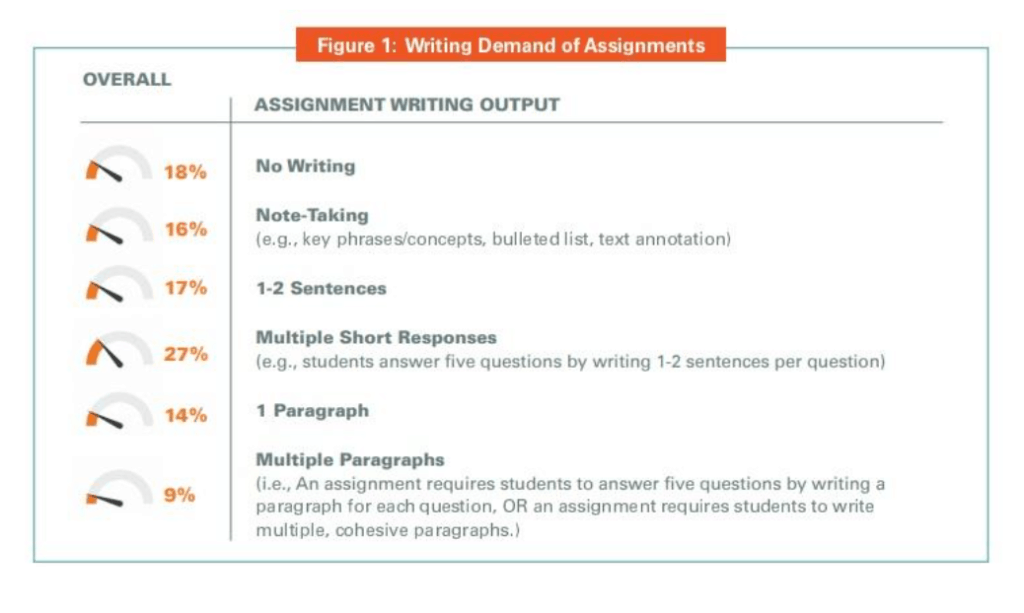

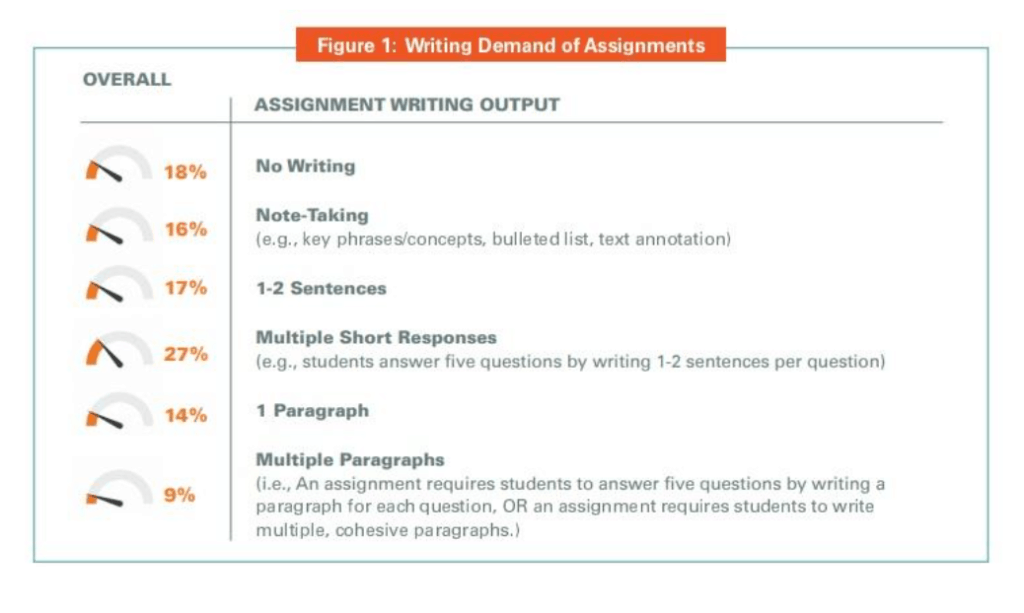

Studies show the trend away from quality writing instruction which picked up steam following NCLB still continues today. A 2015 study of U.S. middle schools by the Education Trust found that less than ten percent of assignments required writing longer than a single paragraph, and nearly twenty percent of assignments required no writing at all. In fact, only one percent of assignments required students to think for extended periods of time–the kind of thinking required to plan, draft, revise and publish meaningful writing.

I reached out to postsecondary writing instructors across North Carolina to investigate trends in their students’ writing. The common refrain in their responses was that student writing skills had diminished over the past 15 years and that it appeared that writing had not been a priority in their students’ previous classes. Many of these instructors spoke of their students’ inability to write in complete sentences with proper grammar and punctuation, to structure their writing effectively, and to provide support for their views. They told me students often didn’t know how to research or how to paraphrase the words of others in their writing. Unable to make up the necessary ground in four years, these students are then entering the job market with subpar writing skills.

The overall decline in student writing ability cannot be attributed to one cause. Recent studies have shown that many teachers are ill prepared to teach writing when they enter the classroom. Others are great at teaching it but lack time to give their overflowing classes the meaningful feedback so critical to improving writing. Technology continues to impact our patterns of communication as well, in some cases eroding forms necessary to academic discourse and replacing it with emojis and text-speak. While all of those elements play a role in determining student writing quality, instructional approaches and amount of time devoted to in-class writing are likely the easiest to change.

A 2010 study by the Carnegie Corporation called Writing to Read found ample evidence that writing can dramatically improve reading ability. The authors discovered that combining reading and writing instruction by having students write about what they read, explicitly teaching them the skills and processes that go into creating text, and increasing the amount of writing they do results in increased reading comprehension as well as improved writing skill.

In order for that kind of writing instruction to occur, what is needed is a culture shift toward an environment where all teachers–not just English teachers–believe they have permission to devote meaningful amounts of class time to writing instruction. Reducing the amount of standardized testing will help to free up time teachers sorely need to adequately address weaknesses in student writing. Finally, moving toward a system where writing assessments are designed and implemented at the local level will lead to more authentic and appropriate learning experiences for our students. By refocusing our efforts on student writing, we can begin to equip our students with the ability to effectively organize information into knowledge and be successful writers at the college level and beyond.

Editor’s Note: This post appeared in The Washington Post.