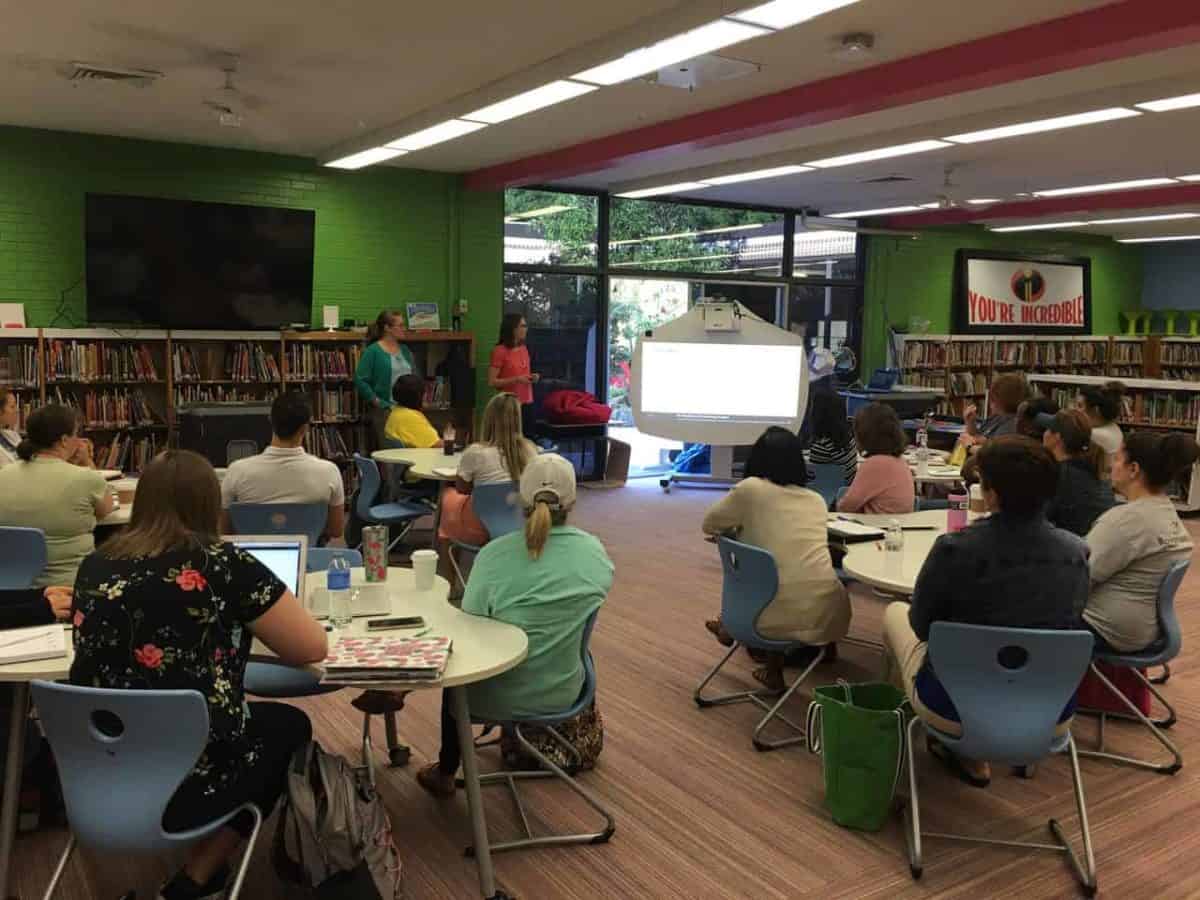

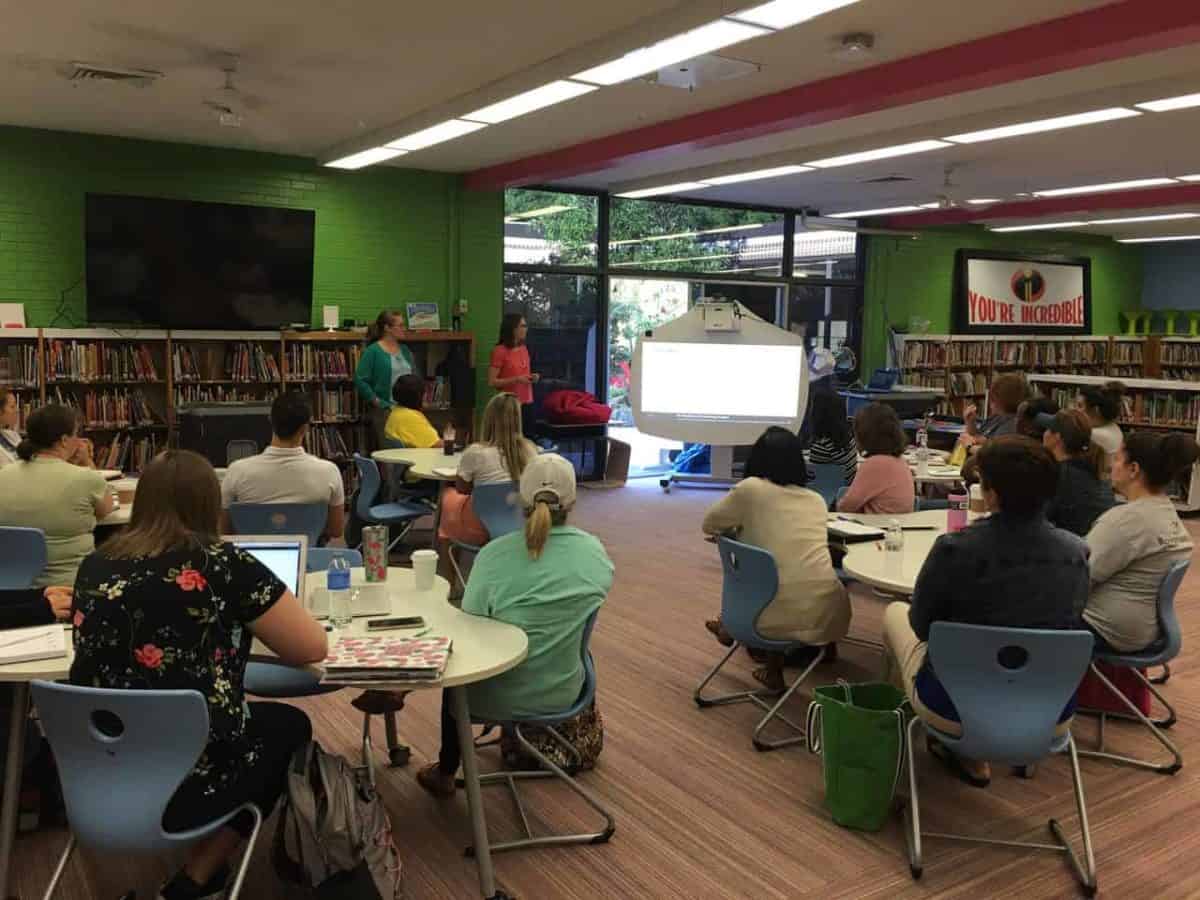

It has been nearly a year since I first met the staff of the three schools that would participate in our NC Resilience and Learning Project pilot year. One of the most memorable days of this past year was the very first training we did with the core teams we were working with at Stocks Elementary and Pattillo Middle, both in Edgecombe County Public Schools.

As we began the training by discussing what trauma is, giving an overview of the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and talking about the impact trauma has on children’s ability to learn, you could sense the shift in the room as more and more staff started having their own personal “a-ha” moments. Throughout the day, staff were talking to each other about the trauma they knew their students were experiencing. We heard stories of physical and sexual abuse, kids coming to school hungry and sleep-deprived and not able to stay awake in class, and students they knew living in homes with domestic violence and substance abuse.

These staff knew so much about their students’ lives outside of the classroom. They knew that they were coming to school with more than just the books in their backpacks. They knew they were coming to school with fear and pain and anxiety and stress and horrific memories, all as a result of what many of them were experiencing at home. And they knew that these traumatic experiences were directly impacting their students’ ability to learn, their behavior, and their relationships with peers and adults.

What these staff didn’t know was how to help these students, yet they were desperate to learn. We talked about the body’s fight, flight, and freeze response and how this is our body’s way of helping to protect us from danger and threat, but how for students who have experienced trauma, they are constantly in survival mode responding in one of these three ways, even at school.

We asked staff to share how they see the fight, flight, and freeze response show up in their students and they immediately began shouting out example after example of how they see it every single day. They see kids yelling and using verbal aggression toward staff and their peers (fight), they see younger kids sprint out of the classroom trying to run away or kids who have horrible attendance and just don’t come to school (flight), and they see the kids in the back of the room who refuse to speak to anyone and prefer to sit alone (freeze). As they made this connection, they became eager to learn what it was they could do to better support these students and create a more positive learning environment.

The last part of our training with them included a time of sharing resources and specific strategy ideas to think about using that to create a safer and more supportive learning environment. There was a buzz in the room as staff started sharing ideas with each other and taking notes on things they wanted to do going into the new school year. The day ended with high energy and with one of the principals coming up to me with her calendar and pen in hand ready to ask us how soon we could come and give the training to the rest of her staff because she did not want to wait another day to get them this information. As the day ended with this level of excitement, I became more eager and excited to get started, and more confident about the value and necessity of the work we were about to embark on.

How it looks inside the school

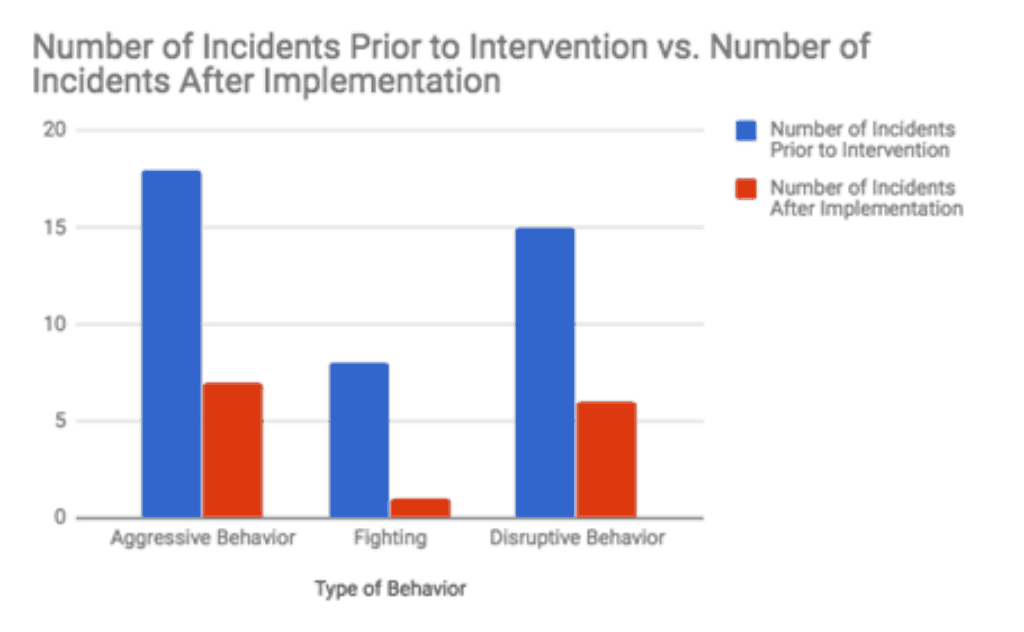

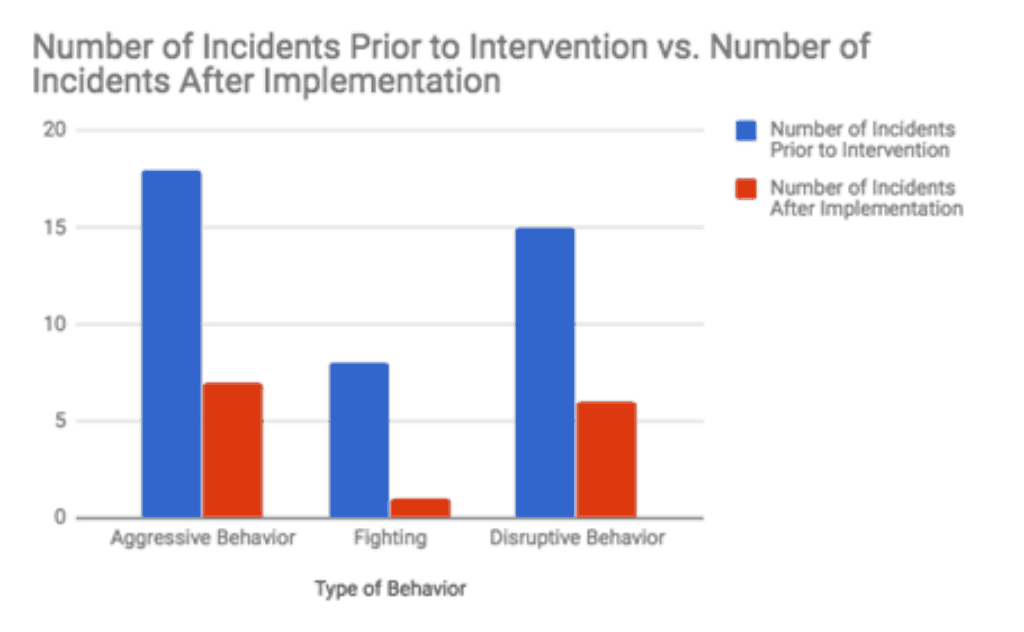

Our model is a whole school, whole child framework to create trauma-sensitive schools that will improve academic, behavioral, and social-emotional outcomes for students. We created our project after pulling together a group of educators and researchers for our 2015-2016 Study Group XVI: Expanding Educational Opportunity in North Carolina that included a focus on trauma’s impact on learning. We modeled our project after other highly regarded initiatives across the nation, which have shown very positive outcomes including: decreases in suspension rates by 30-90 percent; decreases in office referral rates by 20-44 percent; increases in student attendance rates by as much as 34 percent; and increases in student test scores (Dorado et. al, 2016 and Stevens, 2012).

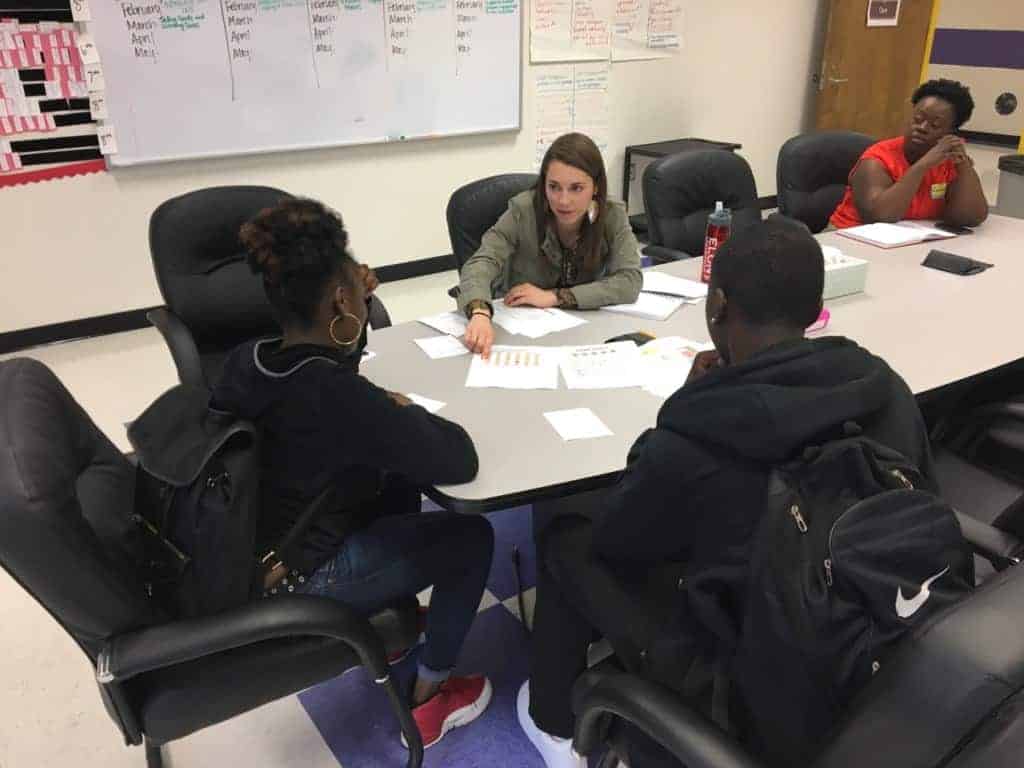

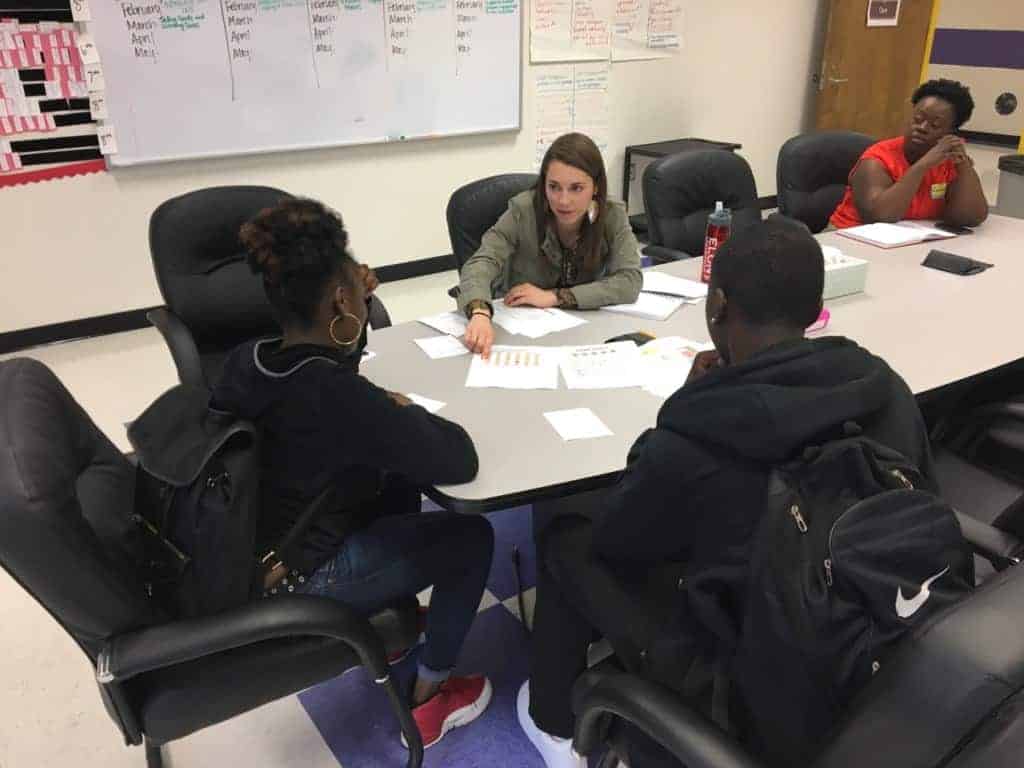

We begin with training and professional development with all school staff and create Resilience teams made up of teachers and administrators to meet regularly throughout the school year with our staff coach.

We saw early on the importance of making this work an ongoing process. The energy after the initial trainings was important but where we began to see a real shift in understanding and creating change was through the work with each Resilience Team that spread across the whole school year. By mid-fall, all three pilot schools were gaining momentum around this work.

All of the schools were beginning to realize that the students with the highest numbers of discipline referrals and who spent the most time in their in-school suspension (ISS) were also the students who likely had experienced a lot of trauma at home. These were the students who were easily triggered by something that reminded them of their trauma, who were constantly scanning the environment around them for potential threat or danger, who could not focus on learning because of what they had experienced at home just hours before coming to school, and who did not have the self-regulation or coping skills needed to calm down when they began to feel that level of toxic stress.

As the schools began having more of these realizations, a real culture shift began. More staff were seeing that reactive punishment and constantly sending kids to the office or to sit at home through suspensions was not working because all it did was isolate them. They were seeing that so many of their kids didn’t even have the understanding, skills, or supportive relationships in place to know how to behave when under stress or how to use positive coping skills and so isolation through office referrals and suspensions was not the answer to teaching them those skills.

They began shifting their discipline polices to an approach that was more restorative, engaging students in the process and using consequences as a way to teach kids skills versus punishment that removed them from the classroom or the school all together. They also began focusing more on building strong relationships with their students so that kids felt safer at school and like they had adults they could trust. Toward the end of the year, a couple of the schools were looking into new ways to better teach kids self-regulation skills because they were learning that just like we have to teach kids literacy, we have to teach them how to express their feelings and skills they can use to calm down.

The culture shift and change process was reflected in anonymous feedback shared with Public School Forum staff through a qualitative evaluation effort that took place throughout the pilot year.

“When you see teachers chatting in the break room, it used to be just a venting session. Now they are problem-solving and brainstorming ideas,” shared one staff member. “Instead of having a chaotic environment that feeds INTO the school, we are building an organized caring effort that extends OUT of the school.”

Staff also began to change the way they interacted with students.

“I try to first start with, ‘Tell me what’s going on.’ ‘Tell me what’s wrong’ so we can get to the root of the problem, instead of ‘Why did you do what you did?’” shared one staff member.

“We have had a lot more restorative conversations with students. We use this cool down area, it has been utilized a lot his year. Teachers have been a lot more attentive to the needs of students,” another team member shared. “I feel like the teachers are calmer when we’re talking to the kids now, and so it makes the whole atmosphere calmer.”

In addition to staff noticing changes in their own mindsets and interactions, they were able to notice changes in their students.

“Instead of acting out, now they’re ready to express, ‘This is how I’m feeling. This is why I’m feeling this way’,” a staff member shared. “I think that our students are more open to verbalizing that they need a minute. Knowing that there is a place for them to go to get that minute, and they don’t necessarily have to tell anybody what’s going on, just to know that they need to cool down.”

The Resilience Team meetings were held twice a month throughout the school year in addition to the initial trainings at the beginning of the year. Through what staff shared as the year went on, it was evident that the trainings were valuable, but in order for real change to take place and new ideas to be implemented, it took a focused team meeting regularly and receiving ongoing coaching. Staff on the Resilience Teams said that, “facilitated resilience team meetings are critical to keep the work moving forward and on the front burner,” and “…we could do small things that would make a big impact. They were our decisions, not somebody else telling us what to do. I think that’s been a big part of what has made this work.”

Moving forward

We started out small in our pilot year with just three schools because we didn’t know what to expect or what barriers we would face.

As we reflect back on the year, we’ve come away with an understanding that school staff are eager to learn about ACEs, staff want to know what they can do to better support students who have experienced trauma, district and school leadership is critical for this kind of project to be successful, and the culture change process is one that takes time and commitment.

As we move into year two with new funding, we are expanding into eight districts and 17 new schools while still providing support to our pilot year schools. We are in a unique position to do this work as a result of the expertise on our team at the Public School Forum, as well our collaboration with incredible partners like the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University with Dr. Katie Rosanbalm as our lead evaluator and researcher and with thought partners like the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, a national pioneer and leader in the movement to help schools create trauma-sensitive environments. We have hired two new regional program coordinators serving different parts of the state and we are entering the new school year feeling eager and excited just as we were at this time last year.

We are continuously learning, and are ready to delve deeper into this work with more schools, to energize school staff, and to assist with the creation of safer and more supportive learning environments for students across the state of North Carolina so that one day soon there will come a time when every student who is asked about how they feel at school will respond with:

“I feel safe, I feel accepted, I feel supported, I feel excited to learn, and I feel like someone believes in me.”