As the nation grapples with the lingering academic fallout from COVID-19, recent results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) paint a sobering picture: Student achievement remains stagnant, and those who were already struggling have fallen further behind.

Yet these national trends mask considerable variation in the progress states and districts have made in ameliorating damage from the pandemic. Several large districts have made significant gains in recovering fourth grade math achievement to pre-pandemic levels. While reading recovery has been more challenging, some districts and states have made notable progress.

Likewise, a quiet success story is unfolding in North Carolina — one that offers hope and a roadmap for recovery.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

A research-practice partnership between North Carolina State University, Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA), and a large district in North Carolina has uncovered promising results from a targeted school improvement initiative. The district’s focus on its lowest-performing schools — designated as Comprehensive Support and Improvement (CSI) schools — has led to measurable gains in student achievement, particularly in reading.

What is a CSI school?

CSI schools are identified by the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) as those in the bottom 5% of Title I schools statewide or high schools with graduation rates below 66.7%. In this perspective, we focus on CSI schools identified in the 2018-19 (Cohort 1) and 2022-23 (Cohort 2) school years.

These schools faced compounded challenges during the pandemic, but many have since exited CSI status after showing significant improvement at the end of the 2021-22 (Cohort 1) and 2024-25 (Cohort 2) school years.

The results: Real gains in reading

Using administrative data from 2012-13 through 2023-24, we compare student outcomes in CSI schools with non-CSI schools that had similarly low performance scores.

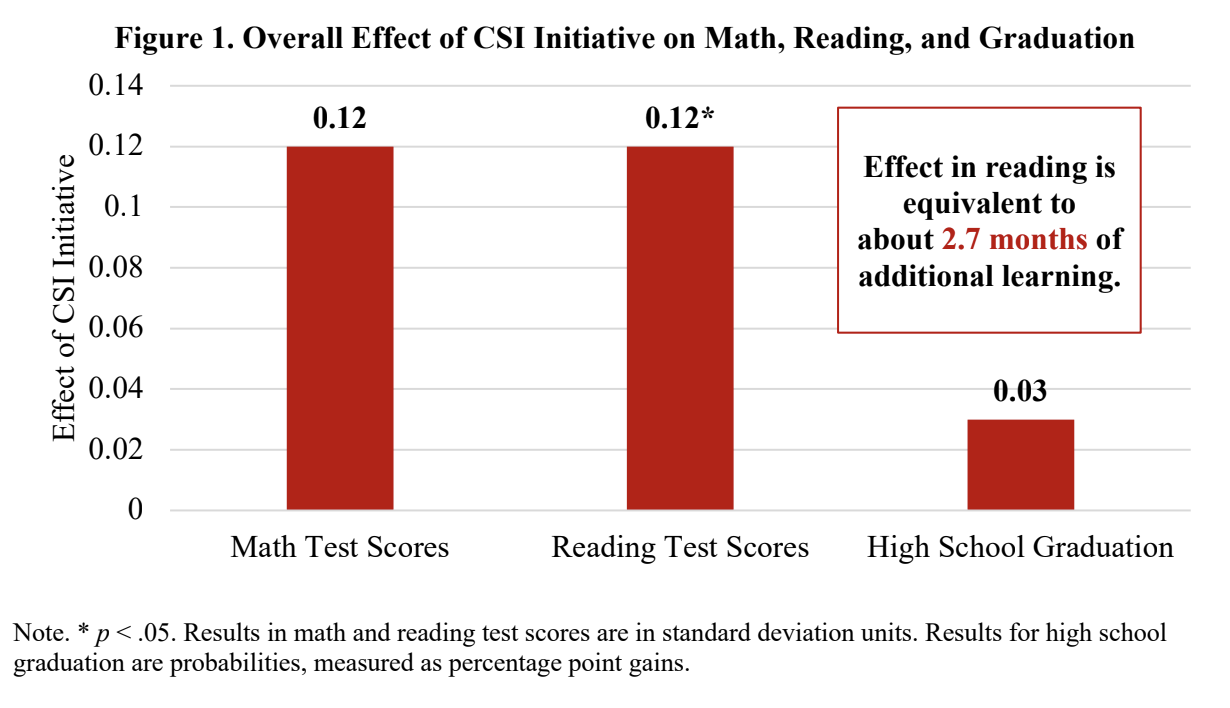

The difference we observed was unmistakable. Reading scores in CSI schools jumped by 0.12 standard deviations — roughly equivalent to 2.7 months of additional learning between fourth and fifth grade. In a post-pandemic landscape where reading recovery has been elusive, this kind of progress is rare and remarkable.

Math and science scores also showed improvement, though the gains weren’t statistically significant. Graduation rates also nudged upward among high schools, suggesting promise, even if the data didn’t reach the threshold for certainty.

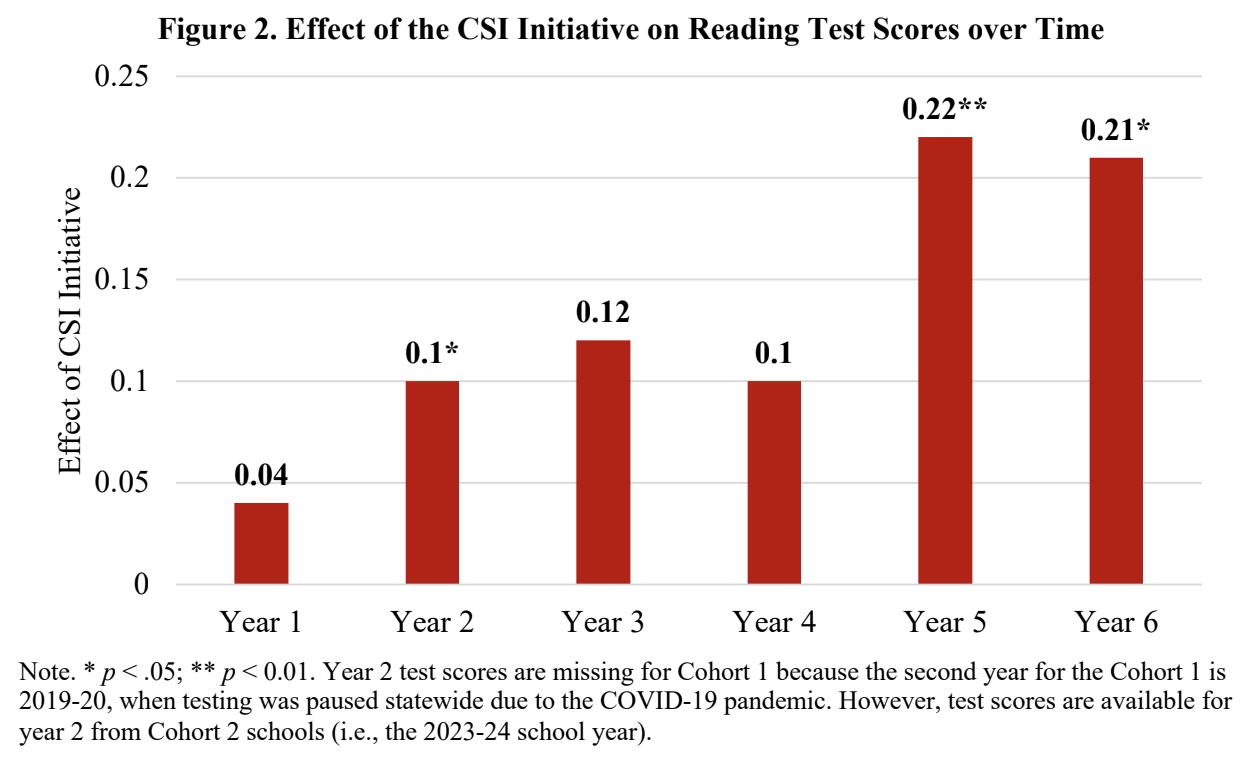

But the most powerful insight came from watching these gains unfold over time. Reading improvements were strongest by years five and six of the CSI initiative. That timing isn’t coincidental. As we elaborate below, this timing aligned with the moment when new principals had fully staffed their schools, built strong instructional teams, and embedded a culture of high expectations.

What worked: The mechanisms of school improvement

To understand how North Carolina’s CSI initiative sparked real academic gains, we spent three years listening to the people on the ground. From 2022 to 2025, we interviewed district leaders, principals, and teachers across CSI schools. We found that CSI schools implemented key school improvement mechanisms that are well supported in prior research and in the district’s own previous accountability reforms. These key mechanisms include:

- Ensuring strong school-level leadership to drive improvement efforts.

- Providing district hiring support and recruitment incentives to fill teacher vacancies and improve staff retention.

- Setting ambitious goals for accountability with a focus on data-driven decision-making and implementation fidelity of district-adopted curricula.

- Building instructional leadership capacity in schools and providing instructional coaching to accelerate growth in teacher practice and classroom instruction.

The vast majority of Cohort 1 and 2 schools experienced changes in school leadership right before or after being designated a CSI school. In the case of Cohort 1 schools, district leaders leveraged recruitment bonuses and networks within and outside of the school district to draw in principal talent.

New school principals brought vision, dedication, and systems-building capacity, often motivated by personal commitment to their school communities. Staff widely recognized the transformative impact of these leaders, describing them as visionary and essential to school success. Leadership stability and quality became the bedrock of school progress.

CSI school principals also raised expectations beyond exiting CSI status, aiming for higher accountability grades and subgroup performance improvements with each year of progress.

Data became central to instructional planning, guiding real-time adjustments and collaborative problem-solving. Curriculum alignment ensured rigorous, grade-level instruction, supported by professional development and structured lesson planning routines. These efforts created a culture of urgency and intentionality around student growth.

Reading gains were especially strong in elementary and middle schools, where improvement plans and strategies zeroed in on literacy.

Related reads

But leadership alone wasn’t enough. The district backed CSI schools with dedicated support to recruit teachers and fill vacancies. CSI principals hired on an earlier timeline, had access to tailored HR support, and received additional state funding to use for teacher recruitment and retention bonuses. CSI schools could also recruit highly effective teachers through a teacher-leader program. Recently, for Cohort 2 schools, the district started coaching principals on building school culture to retain staff — leading to lower rates of turnover and fewer vacancies to fill in following years.

Still, many teachers at CSI schools are new or emergency-credentialed, and school principals knew they needed more than bodies in classrooms — they needed growth. So, they invested in instructional coaching. In most CSI schools, every teacher participated in weekly observations and received one-on-one feedback. Teacher-leaders helped build instructional leadership from within, creating a culture of continuous coaching and improvement.

Challenges ahead: Sustaining momentum

Despite these successes, sustaining improvement remains a challenge. CSI schools receive additional funding and support — but only while they hold CSI status. Once they exit CSI status, resources dwindle, even though the need for continued investment remains. Moreover, meaningful school improvement takes time. In this district, it took five years of consistent effort — from 2018 to 2023 — before results became visible. Policymakers need to recognize that short-term interventions are unlikely to yield lasting change.

While the urgency to improve student achievement in the aftermath of the pandemic remains, targeted efforts to improve low-performing CSI schools can produce impressive results. Our findings show that with robust school-level and instructional leadership, strategic staffing, data-driven accountability and instruction, curriculum fidelity, and intensive instructional coaching, even the most challenged schools can make real progress.

As districts across the country search for solutions, they should look closely at what’s working in North Carolina. The path forward is not easy — but it is possible.

Recommended reading