|

|

Black students in North Carolina are more likely to face disorderly conduct charges and referrals to law enforcement than their white peers, a report released by the ACLU of North Carolina revealed.

Michele Delgado, a staff attorney for the ACLU of North Carolina and the editor of the report, said mental health remains a huge problem for children. She also said the reliance on police officers in schools isn’t serving or meeting the needs of students, especially Black students and Black students with disabilities.

“It’s really not beneficial to students in learning settings, and it just stigmatizes Black students and students with disabilities,” Delgado said. “It doesn’t really support what they have going on or just their needs.”

To cut down on over-policing and mitigate the school-to-prison pipeline, Delgado said the state needs to focus on a real problem affecting students: mental health.

The state needs to invest in more school personnel, like counselors and mental health professionals, Delgado said, rather than investing money in policing in schools.

“It’s clear that policing of students is not working and that our state should look into doing some other things and trying something new, something that really supports students versus criminalizing them,” Delgado said.

‘The numbers in black and white‘

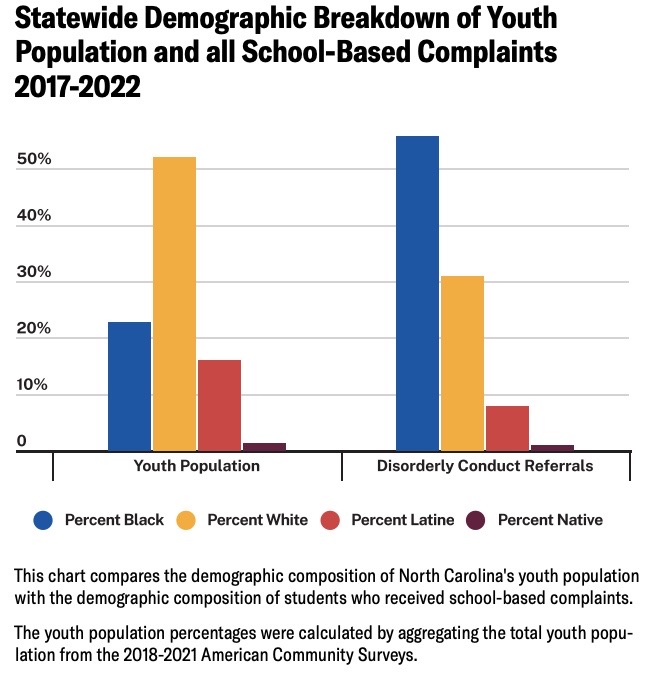

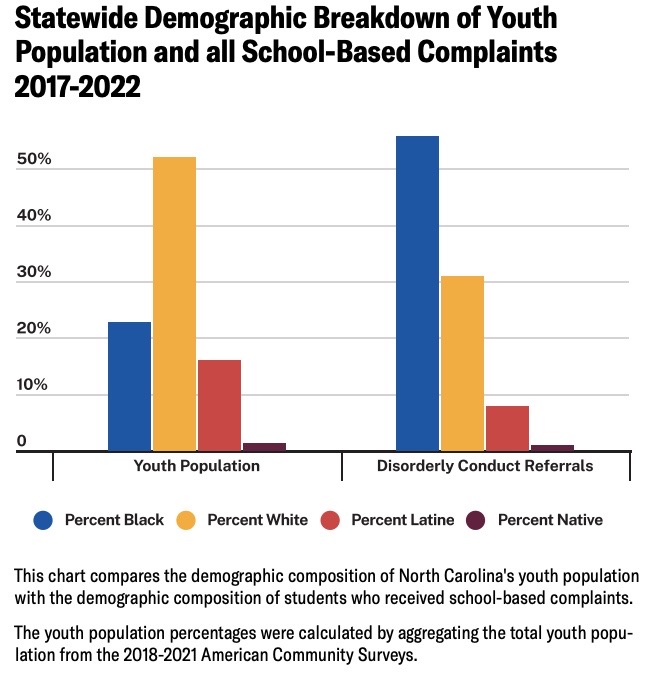

The ACLU found that though white youth make up a majority of the population, Black youth make up a majority of law enforcement referrals in schools.

The report also found:

- Black students get referred to law enforcement at 2.44 times the rate which white students do.

- Students within the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) face referrals to law enforcement 2.45 times the rate which non-disabled students do.

- In schools in 25 counties, only Black students were referred for disorderly conduct from 2017 to 2023.

- In five counties — Gaston, Forsyth, Moore, Wake, and Pitt — Black students are referred at a rate 23 to 42 times higher than their white classmates.

Delgado said she wasn’t necessarily surprised by the findings of the report, but did feel shocked by the enormity of the disparity in some cases.

“Seeing the numbers in black and white just more so disappointed me,” Delgado said.

Police in schools

Police in schools, also known as school resource officers (SROs), serve as either law enforcement officers, law-related counselors, or law-related education teachers, according to the the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI).

The National Association of School Resource Officers recommends SROs receive 40 hours of training before beginning to serve in schools, DPI reports.

Flint, Michigan had the first program inserting law enforcement officers in schools in 1958, according to the National Policing Institute (NPI). Adding police to schools was originally done to bolster officer-student relationships.

Other schools began implementing their own programs, NPI reports, and since then, lots of school programs like Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) have relied on police to instruct students.

Despite the addition of SROs to schools, incidents of student crime and violence in North Carolina continue to occur. The annual school discipline report for the 2021-22 school year, released in March, showed a total of 11,170 acts of crime and violence in North Carolina schools. This was higher than the 1,535 acts the previous year during the peak of the pandemic, and higher than the 7,158 acts in the 2019-20 school year.

DPI’s website says SROs do not contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline but rather help youth stay away from the juvenile justice system.

Delgado said the disproportionate law enforcement referrals for Black students do play a role in the school-to-prison pipeline, and create a lack of trust toward police among students.

“This over-policing of students is really making them feel less safe, not more, and has created an environment of distrust and fear,” Delgado said.

Decriminalizing ‘childish behavior‘

Schools relying on law enforcement referrals often criminalize what Delgado called “childish behavior.” Delgado said she wants schools to focus on meeting and treating the real needs of students instead.

“Students are children and their actions and outwardly behavior issues, sometimes they’re stemming from something, right? And so let’s decriminalize their behaviors and really look into investing in resolving what issues are going on,” Delgado said.

Delgado said schools also need to stop the use of the disorderly conduct statute, which criminalizes behaviors in schools including disturbing or interfering with teaching, disturbing the peace on a school bus, blocking or interfering with the operation of a school facility, and more, which could mean a misdemeanor for a first offense or a felony for a second offense. The statute is too vague and leaves room for implicit bias, she said.

She said she hopes parents can get more involved and advocate for expanding mental health providers and workers in schools. She also said she wants equity assessments of the police’s impact in schools.