There I was, armed with dry erase markers and clutching a whiteboard like a shield. With my son by my side, I was ready to be a remote learning hero.

I planned and researched, made schedules and lists. Meal prep, check. Clutter-free workspaces, check. I imagined every conceivable obstacle, and charted a course for balancing my work with supporting my son’s remote learning.

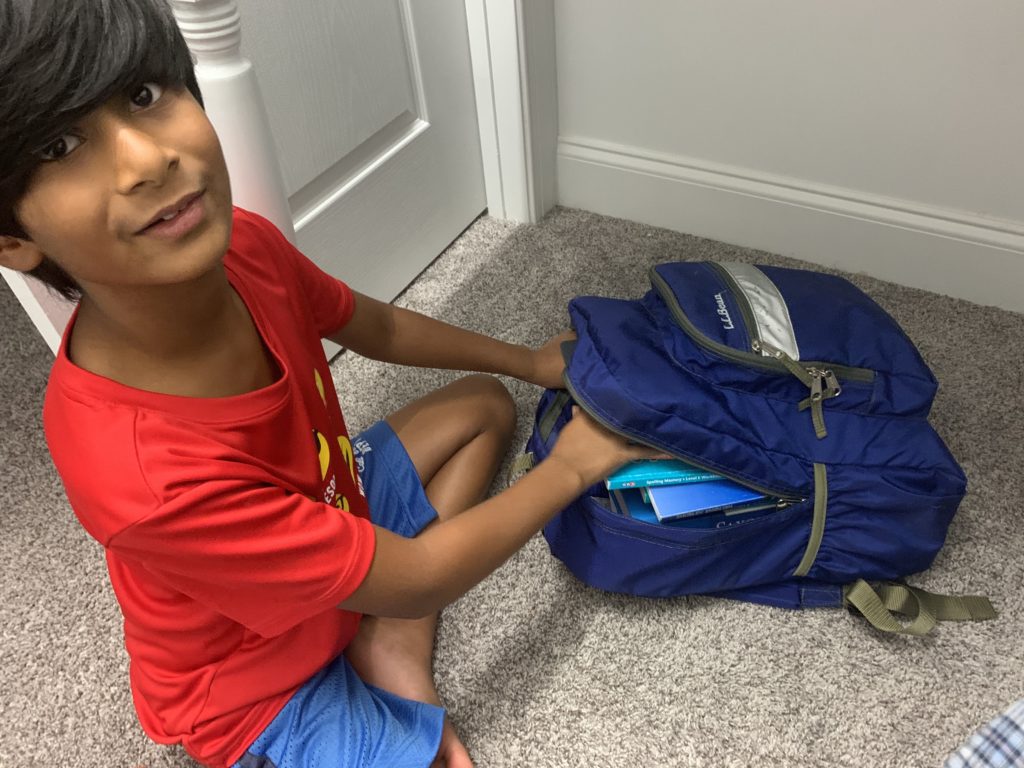

Then I fell flat on my face. Right beside my 9-year-old, who lay on the ground crying because he felt overwhelmed. Already. On Day 1. At 8:30 in the morning.

That’s when I decided to call Hill Learning Center for help with remote learning. I thought of Hill because of something executive director Beth Anderson told me in the spring.

“What you’re talking about is ‘executive functioning,’” she had said after I described my son’s fourth-quarter struggles after the pandemic hit. “It’s so important for every student, any time — but now, especially, developing those skills is going to be vital.”

Executive function skills allow my son to organize his day, start on a task, and transition between assignments. All while avoiding the many distractions around the house.

A school’s curricula, no matter how strong, are wasted if a student can’t find an entry point. Executive function skills are the key.

“Hugely important,” says Kathy Sullivan, director of professional development at Hill. “It’s that ability to set goals and to get started on something even when you don’t want to.”

So what can you do to develop those skills during this remote-learning year? Here are five tips for students and parents, and five more for educators.

5 things parents and students can do to navigate the remote school year

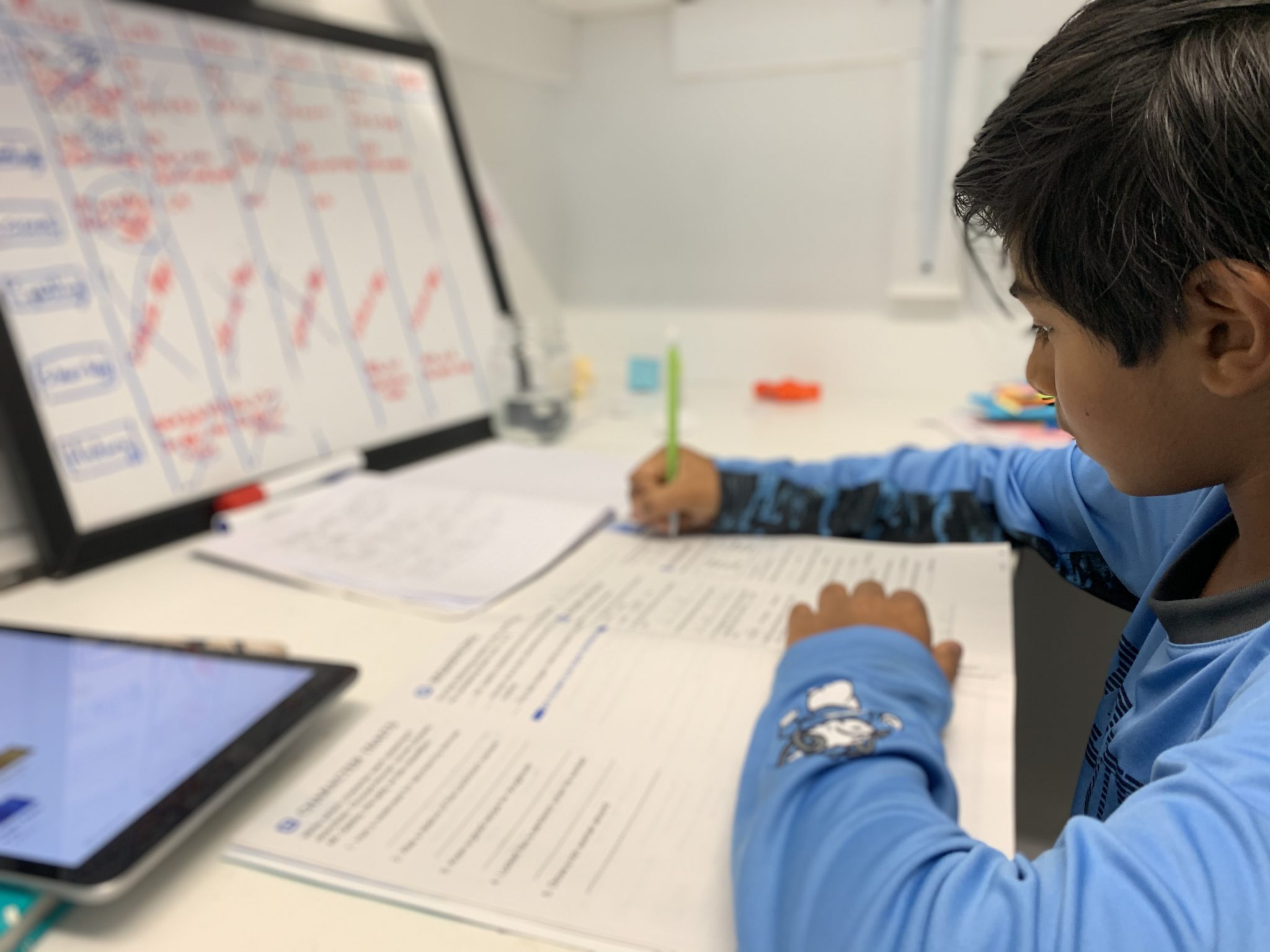

1. Organize a remote learning space

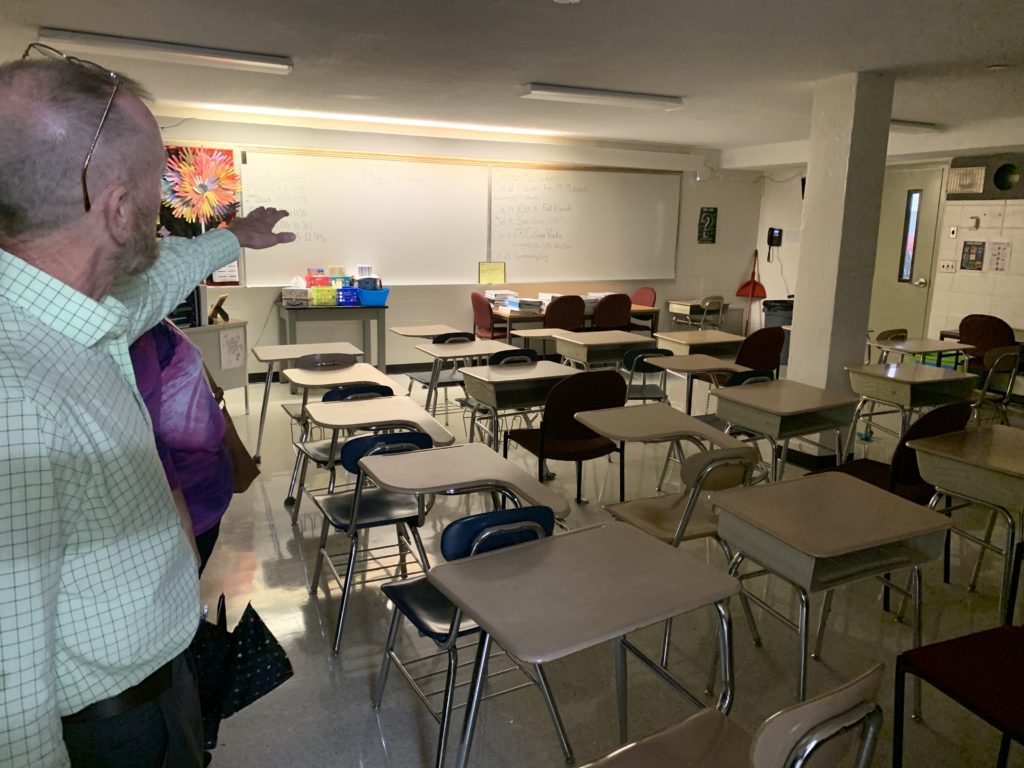

The first thing you might notice about a classroom is its organization. Cubbies and shelves lining the walls, desks and storage bins labeled with student names, a place for keeping everything neatly.

We had to create that kind of space for my son at home. Before we did, he floated from sofa to table to bedroom. Nothing — his focus included — was ever in the right place.

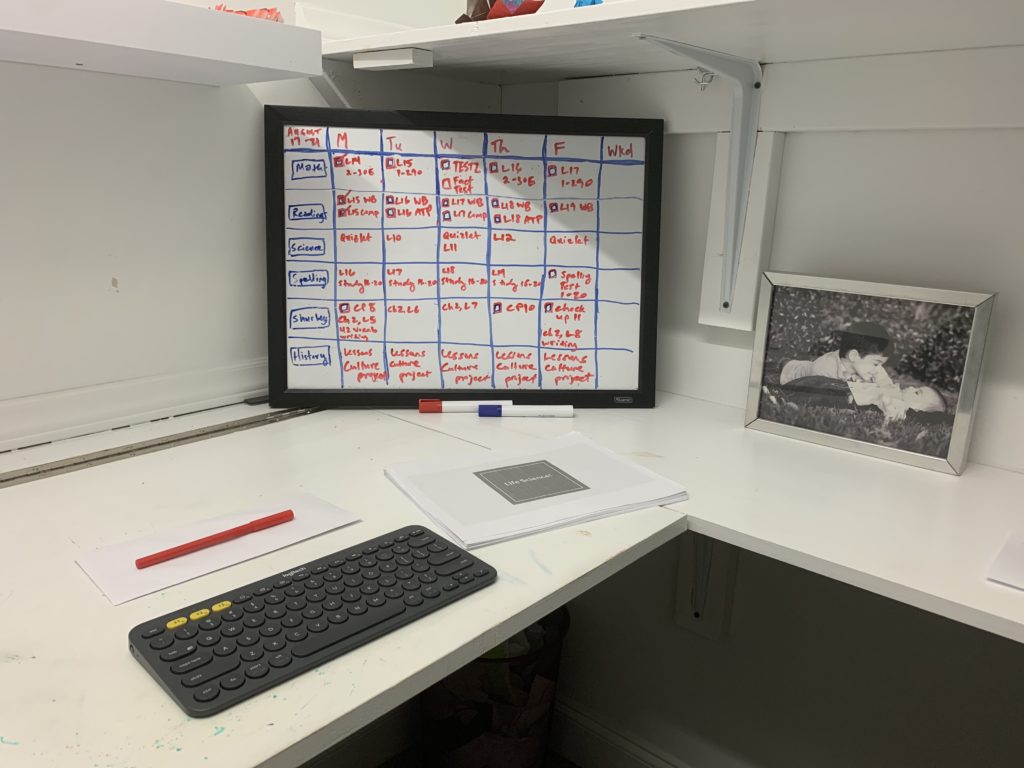

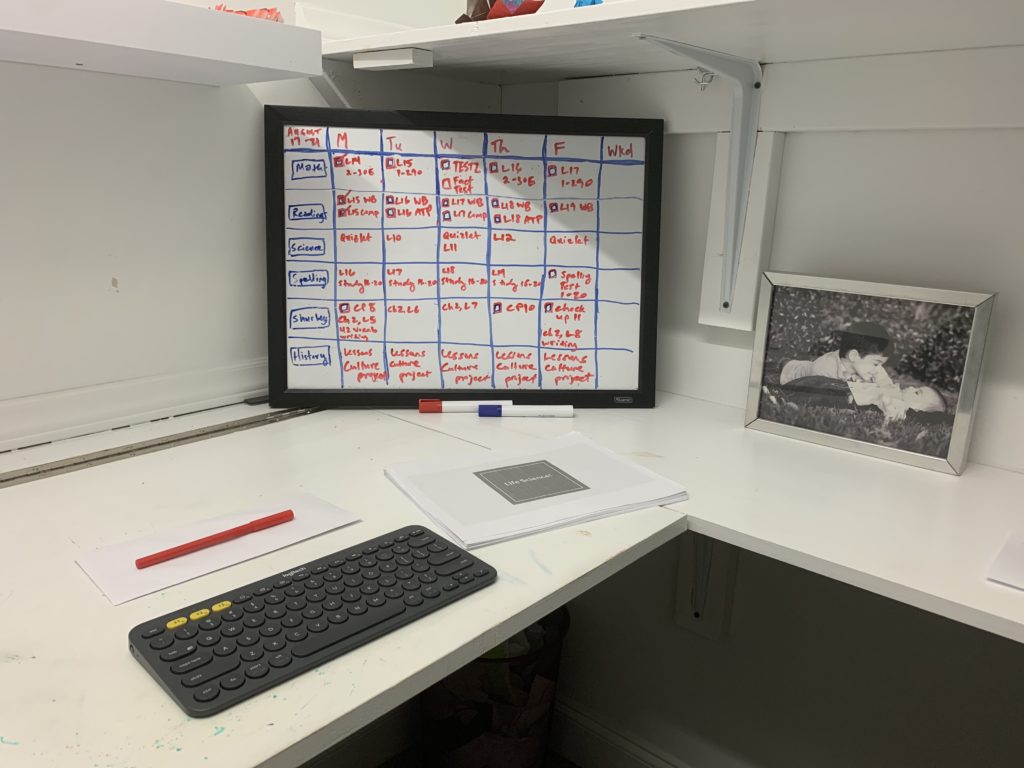

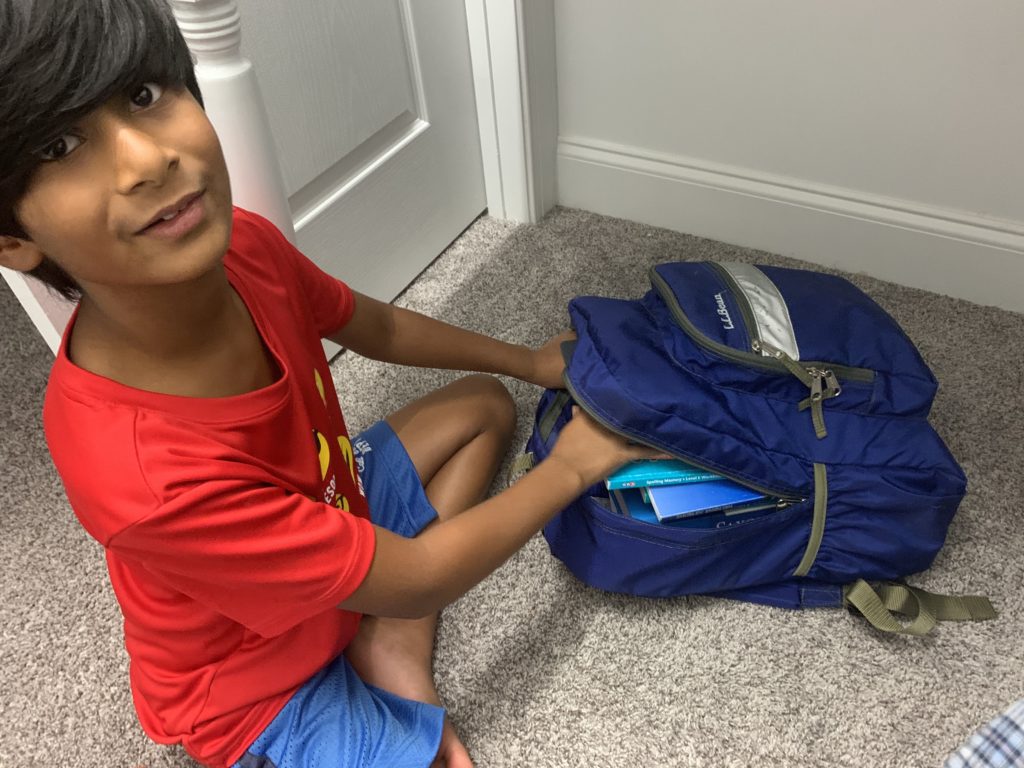

We repurposed a closet with room for a fold-down desk, a chair and some shelves. His books, device and a printer stay there – along with a whiteboard where he keeps track of assignments.

“From the time a child walks into a kindergarten classroom, you’re teaching them here’s where you hang your coat up and here’s where your lunch goes and here’s your folder for this,” Sullivan said. “At some point, third-, fourth-grade, we start to make that transition into them taking ownership of their organizational style and how they best do things. The quicker you can get a child involved making those decisions for him or herself, they own it then. This is a strategy.”

2. Organize your day

It’s not easy for teachers to convert entire lesson plans, deliver them on demand and navigate submitted assignments. Teachers deserve grace, even more in these times.

But so do parents and students.

It takes at least a half-hour, clicking subject by subject, to find all of my son’s assignments. But it’s time well spent. His classwork and homework are not all found on one page. There’s at least one page for each subject, and more than one for some.

As he’s trying to get through his day, my son is prone to skip a link or two. He also feels haunted by this sense of never-ending workload if he’s blindly tackling things as he clicks on them. When he makes a list of everything and can see it all in one place, he can prioritize. He also feels a sense of accomplishment as he crosses off items.

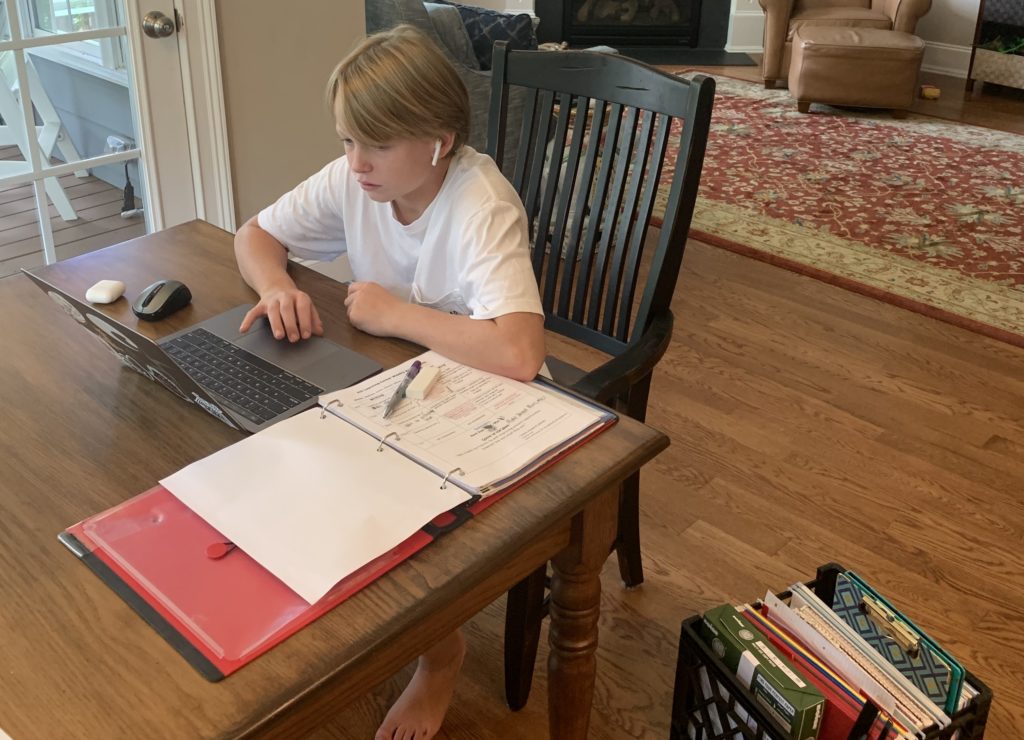

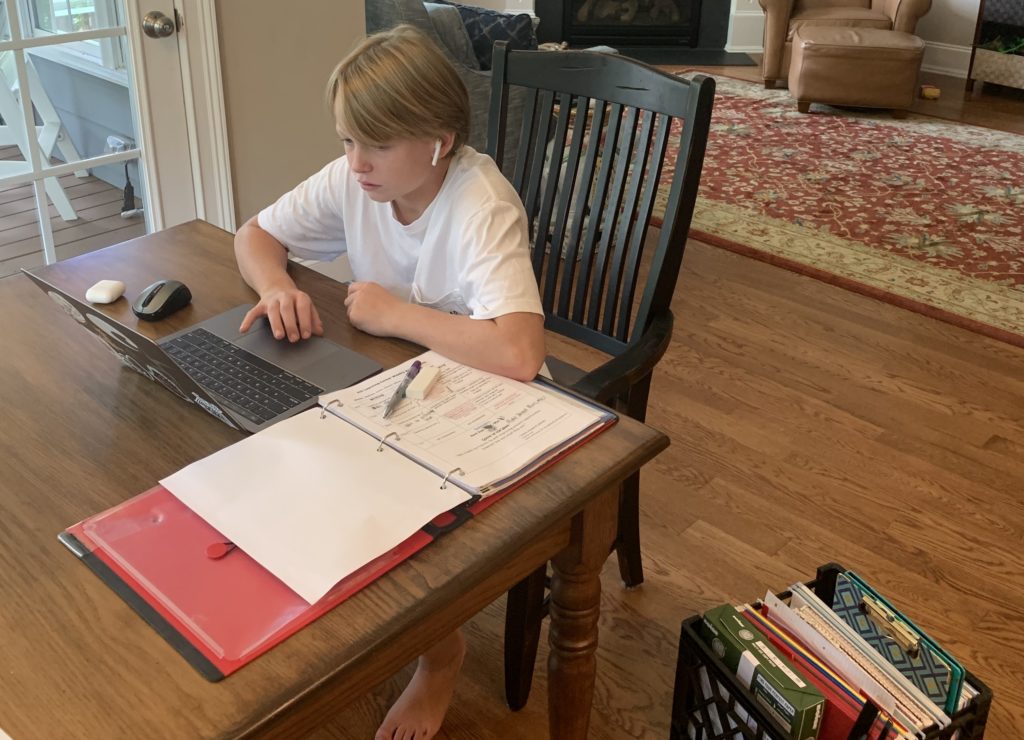

Nathan Moeller is a rising seventh-grader at Durham’s Sherwood Githens Middle School. He takes a similar approach, heavily recommending a schedule and some organization.

“Always have a schedule to see what you need to do,” Nathan said. “Look at it before every class. And try to keep all of your stuff in one area, but divide it up for every subject. It will help you to know where everything is because you put it where it belongs.”

3. One thing at a time

Stephen Baker, 11, is used to learning from home as a homeschool student. He’s benefitted from Hill’s methods for about four years. Of all he’s learned so far, he likes keeping a plan, but says focusing on only one thing at a time is important.

Stephen would sometimes feel overwhelmed. When that feeling bubbled up, he learned a strategy to handle it.

“I just say to myself, ‘Hey, it’s going to be OK,'” Stephen said. “It’s not that much. Just think about one thing at a time. I like to get everything done and over with, but I just do it one thing at a time.”

Hill teaches students like Stephen to use agendas or calendars to track assignments by the week, day or even hour. Not every student prefers the same organizational system, Sullivan says. It’s important to pick something, though, and to keep trying new systems until you find an acceptable one.

“Just check in with them and say, ‘OK, how did that work out? How did that feel? Do you want to try this instead?’” Sullivan said.

4. Make time for processing

The time between tasks — as students finish an assignment and before they begin the next one — is valuable. Meaningful transitions between assignments can help new information sink into a child’s brain, Sullivan says.

“One of the things that we do that’s so, so simple if people would follow through with it,” Sullivan said, “is, when you are transitioning from one task or subject to another, take just one or two minutes to process. And literally we set alarms on our phone — and for that two minutes say, ‘My promise to you is that I’m going to stop teaching. I’m not going to give you any new information or anything you have to hold on to. Your promise to me is that you’re going to take the time to file those papers where they belong, look up at the board and take a moment to finish filling in that note or make sure you have your assignment down.’ … That two minutes to process and assimilate makes a world of difference.”

We started doing that with my son, and he keeps a sheet of paper with him during his processing time.

When he’s finished with a subject, he puts away his books and files his papers. He sets a two-minute timer to reflect on what he’s learned.

If something didn’t make sense in a lesson or assignment, or he has technical issues submitting work, he jots it down.

Finally, after gathering materials for his next subject, he closes his eyes again and imagines what he’s about to do.

5. Practice, practice, practice

At my son’s school, he’s on average about six or seven clicks away from what he needs for each subject. It’s too many. While we practice compassion and grace for his teachers, we’re also practicing navigating all those links so he doesn’t get lost.

We’ve spent hours going through the motions, sequentially. We start with the math module in Canvas: click here, click there, click back here. We go through the entire process he’ll need to navigate each morning until he feels comfortable.

We’ve spent enough time looking at each landing page that he’s starting to recognize apps and websites the same way he would recognize new halls and rooms in a school.

“Like everybody, we’ve heard the same story over and over; we all struggled in the beginning,” Stephen’s grandmother, Pam Johnson, said about last quarter. “But after he kept at it, by the end of April or May, we started to figure things out. Stephen would just come in and he had his schedule all laid out, and he just moved through the day all by himself.”

As with many things, practice is the key.

5 ways educators can promote building executive function skills remotely

1. Prepare explicit and direct instructions for remote learning orientation

When students start back, virtually, at Hill on Aug. 25, the first four days will be reserved for orientation. Much of that time is for establishing and modeling executive function skills.

Instructors will ask to see students’ workspaces, checking for good lighting and clutter-free space.

They’ll ask students to make sure they have all their materials. They’ll talk about calendars and agendas, and help students determine organization preferences.

“If they don’t know, we have a few suggestions we’ll help them try to see which one works best for them,” Sullivan said, “and then we’ll check back in. So we’ll be spending time putting all of that in place.”

2. Managing point-of-performance advice while students are learning remotely

Executive functioning isn’t a subject in school; it’s something students need to learn for success in each class they take. So teachers are constantly teaching these skills.

“It’s like the wrapping paper that goes around everything; that’s how I want teachers to see it,” Sullivan said. “It’s integrated, not a separate subject. You do it at the point of performance.”

In school, teachers saw when executive function skills needed some attention. They could pause a student at the “point of performance” and teach organization or transitioning, or address impulsiveness.

“We’re losing a little bit of that now,” Sullivan said of the move to remote learning. “And so we will just sort of have to troubleshoot as things come up. But we’re prepared to make the time to do that with each and every student. That means having one-on-one check-ins with them to ask how things are going or talk about the couple of assignments that came in late. It’s asking how we can help. It’s not punitive, it’s about coming up with a strategy to solve problems.”

3. Be intentional and collaborative with materials

I’m fortunate to be home to help my son, but he needs lots of help to get started. There are seven places where his assignments and homework are listed. There are three apps where teachers record lessons.

Sullivan implores educators to avoid stretching students’ minds in so many directions.

“We shouldn’t set it up so that you have to be right on top of your child,” Sullivan said. “If we’re doing what we need to be doing, and explicitly front-loading all of that, the child ought to be fairly independent.”

What should educators do on this front? For starters, minimize the number of links students must click to find lessons or assignments. Then, coordinate with other teachers to limit the number of applications students need to download and use. Finally, compile information in as few places as possible.

“We give them a one-stop sheet that has all the URLs,” Sullivan said. “And then, in addition to that, we’ve thought it through as a school because a teacher shouldn’t have any child more than two or three clicks away from what it is you need them to do or submit or read.”

4. Engage with adults as teacher’s aides

With students often out of sight during remote learning, teachers rely on check-ins to catch executive function deficiencies. So while Sullivan hopes teachers don’t inundate parents with extra responsibilities, she says it’s helpful to engage them as coaches.

“Parents are really the ones who will see these things and pass them on in person,” Sullivan said.

She suggests talking to parents about executive function skills and how to support building them.

“It’s important parents are learning how to coach,” Sullivan said, “and not to do for their child.”

5. Invest in executive function training

It might seem you don’t have time to invest in learning how to develop your students’ executive function skills. Sullivan says the investment pays handsome dividends.

“Let’s talk about how much time you’re spending as an educator chasing down that child’s assignments or tracking down things from them,” she said. How much time is wasted in asking where things are and where the student went astray, “versus teaching a man to fish.”

Hill offers workshops. In September, Hill is hosting a free 90-minute seminar, led by its executive function coordinator Geraldine Pesacreta. You can register for that here.

The Friday Institute also has developed a MOOC-Ed for educators looking to strengthen the executive function skills of their students. The course began this summer. You can find registration details and watch for future dates here.

A silver lining amid challenging times

With remote learning, executive function skills are of greater consequence. Sullivan says the need to practice them earlier and more often might be a blessing in disguise.

Learning math and reading, science and history – it’s important. But learning how to access those subjects, indeed mastering the very process of learning, is training that will pay off for a lifetime.

“Right now, it’s about getting assignments completed and turned in,” Sullivan said. “And later it’s going to be about receiving bills and getting those paid on time. There’s a direct correlation to what you’re going to be doing for the rest of your life, so the sooner I can give you those skills [the more] you’re going to be successful.”