Schools closed so quickly when the pandemic hit in March, Hayden Moore couldn’t wrap his head around what was happening.

Moore is a 20-year-old student at Davie County High School with autism. He thrives on routine, social interaction, and one-on-one support. When all of that went away, he felt a little lost.

“That was a very hard transition for him,” said Natalie Moore, Hayden’s mom. “With most autistic kids, and Hayden included, he’s been taught from a very early age that he needs to interact socially, and he thrives on routine. And when it went from, this is my structure, this is my schedule, to, I don’t get to go back — that was very hard for him.”

As state orders and guidance shift and public school units consider what plan to proceed under, teachers and parents of students with special needs — or Exceptional Children, as they’re called in North Carolina — are watching closely. Two places worth a look, said Sherry Thomas, director of the state’s exceptional children division, are Davie County Schools and Brevard Academy, a charter school in Transylvania County.

Under the state’s plan B, these two public school units have taken similar but slightly different approaches to find ways to provide individualized instruction to Exceptional Children, focusing on creative ways to bring them into school buildings safely.

“There’s kinks to work out, and the plan isn’t perfect,” said Kaylin Royals, an EC teacher at Cornatzer Elementary in Davie County. “But I think that if everybody had their way, there’d be no COVID and we’d be in school five days a week. But that’s just not the case right now. So, I think moving forward, we’re really just doing the best we can and just really working together and collaborating to make the best of the situation.”

The situation right now

Parents say kids aren’t getting the same services during remote learning as they were in school, before the pandemic.

Some parents report behavior problems at home because students aren’t receiving support or are frustrated with altered routines, said Brevard Academy EC Director Lois Luhrs. Jennifer Custer, the EC director in Davie County Schools, has also heard from working parents that it is difficult to find child care for their kids learning at home.

“For children with more intensive needs,” said Custer, “it’s hard to find another respite person or a caregiver to take care of them.”

The remote learning environment can also be confusing: When to show up where, for how long, and how often. How to pull up documents. How to submit assignments.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

“Some do not do well with computer screen time,” Custer said. “It’s confusing to them that their teacher is on this little bitty screen, but she’s not in front of me like in class. We’ve not practiced that with them before.”

Some of these issues were resolved under plan B. At most schools, this means an “A-day” cohort of kids attending in-person on Mondays and Tuesday and going virtual on Thursdays and Fridays – with the “B-day” cohort doing the reverse.

But for special needs kids, going to school some days and staying home other days is even more confusing than being home all the time.

“I think that would have been more disjointed for him,” said Moore, who is a school nurse in Davie County in addition to being Hayden’s mom. “He just needs more routine and consistency than that.”

How Brevard brought EC kids back

Brevard Academy is a K-8 charter school in Pisgah Forest. It has about 45 EC students, mostly kids with specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia or focus and attention issues.

The school opened under plan B, with an A day/B day format. But Luhrs worried after watching many EC kids fall behind during emergency remote learning in the spring. During a meeting with her EC staff, she wondered out loud: “Could we bring them in extra days?”

The school has brought the most critical cases into the school building four days a week, and even found a day of in-person instruction reserved only for those cases where the student or a family member has significant medical concerns.

“Some of those kids are our [most struggling] learners,” Luhrs said of the medically vulnerable cases.

Wednesdays were reserved for teacher planning and virtual check-ins. Realizing that no other students would be in the building that day, they offered in-person Wednesdays to this “fragile” subset of kids. Four families accepted the offer.

The staff worried about leaving six EC students at home in plan B three days a week. Either family situations would make connecting online a challenge, or behavior issues were more likely to boil over at home.

Luhr and her team invited these kids to come into school four days a week. They spend their two scheduled days in general education and the two “bonus” in-person days receiving EC support.

“I’m doing it because I have a dedicated staff willing to do it,” Luhrs said. “We didn’t have to do it; we could have just gone with the two days. But we have really good relationships with our parents and with our children. And we knew that leaving them unattended for three days could be really detrimental to their progress.”

How Davie County is supporting ‘extended content standards’ kids

In Davie County Schools, all kids in self-contained classrooms were invited in-person four days a week. These are EC students receiving extended content standards – instruction beyond the state standard course of study.

“Long weekends for students with those types of concerns can be hard,” Custer said. “So you even worry about interrupting routines for things like Labor Day. So A/B days, I don’t know if that could really work for them.”

Rather than have these kids come in two days and stay home three, the school brings them in Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday.

“It has been such a positive for those students as I have visited those classrooms,” Custer said. “They are in more of a routine and structure for them, which is so important for their needs. You know, to come on an A day and like Monday and Thursday —just the confusion of all of that, I think, is harder on them. So this has really helped them.”

The district has also found ways to involve students whose families want them to stay home. In some classes, virtual learners visit the classroom for short periods to get one-on-one help and see their friends. In others, like Royals’s elementary classroom, computers are set up at virtual students’ regular desks and the virtual kids join the classroom that way.

“It’s really great to see the looks on the faces of the kids in the classroom when their friends log in,” Royals said.

Things are working well enough in Davie County that parents in neighboring counties are taking notice.

“I just got my second call yesterday from a parent in Forsyth County who would pay out-of-county tuition to bring their kids here, because we’re four days a week.”

Safety first, innovation second

At Davie, before Custer could implement four-day in-person for her students with significant impairments, superintendent Jeff Wallace had a question.

“He said, ‘You’ve got to talk to me about the safety, Jennifer,’” Custer recalled. “And I said, OK, here’s the deal.”

The self-contained student population is already small, with no more than 12 kids in any class — so distancing is feasible. Working with maintenance staff and teachers, other measures were implemented, too.

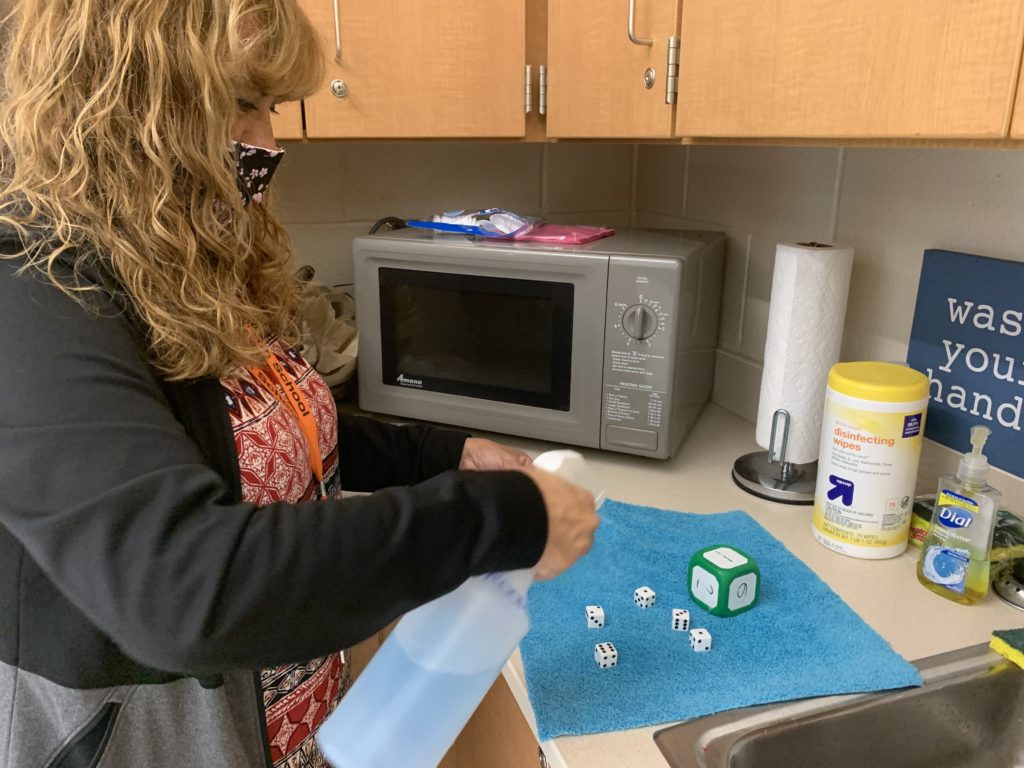

Wipes and disinfectant are on hand, masks and gloves are used, and teachers emphasize hand washing. The maintenance department built plexiglass stands to help prevent students from leaning into other people’s areas.

“I feel like the dust is still settling a little bit,” Royals said. “I feel like we are getting a more comprehensive, consistent plan together. We’re still going to have speed bumps and just, you know, inconsistencies that are going to happen.”

Over the first four weeks, the district and individual schools have added more measures. For instance, large trash cans line the middle of the hallways at Davie High School now. That was a change after classroom trash cans began overflowing since students eat in their rooms.

“A lot of blood, sweat, and tears went into the planning, but you know, three weeks in, you can really see it coming together,” Custer said. “The safety measures are in place for the social distancing and the masks and the cleaning, and it’s coming together. So that’s a good feeling.”

Moore added: “You tweak and you regroup and you say, OK, this doesn’t look like it’s working so we’re gonna try something else.”

What it looks like

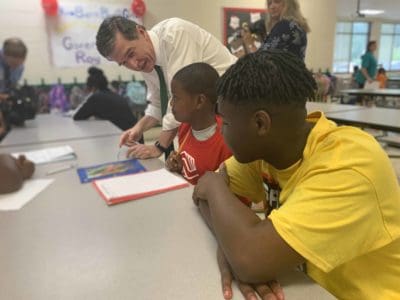

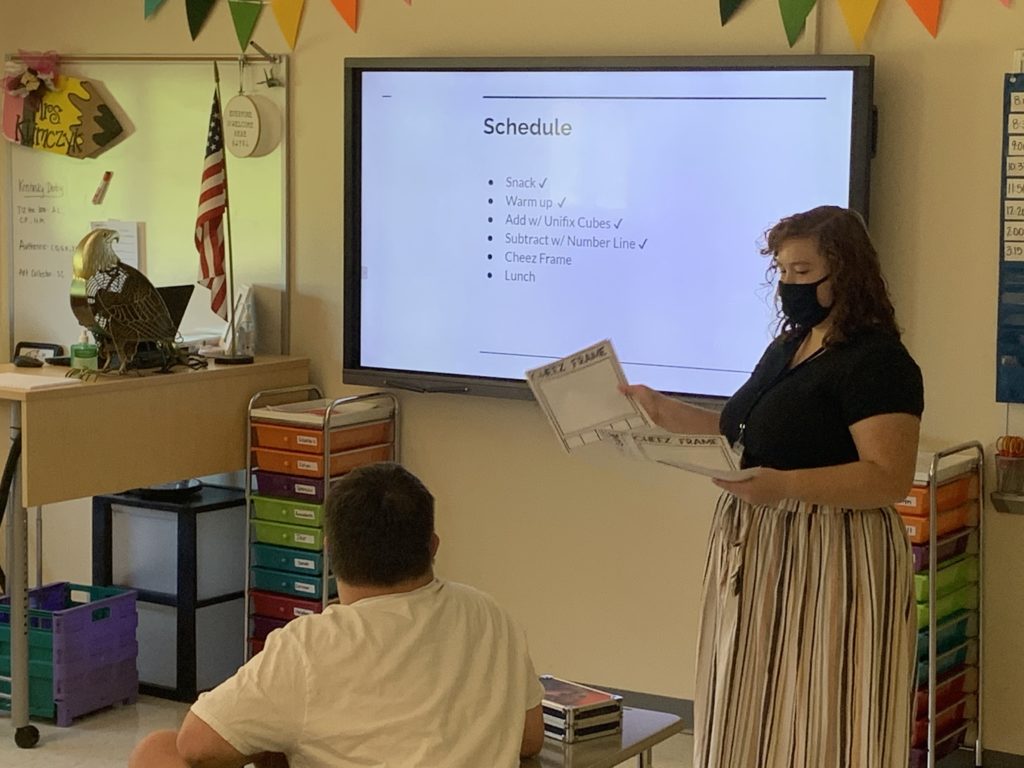

At Davie High, EC students in Brandi Klimczyk’s class are rolling oversized dice to help their teacher fill in numbers for an equation on the board. One student rolls a four. Another rolls a two.

“So where am I going to start on the number line?” Klimczyk asks, and the students shout, “Four!”

As the students and teachers go back and forth working out the equation “4 minus 2,” an aide is at the sink disinfecting the dice. The students aren’t paying attention to the cleaning, though. They’re laughing and learning.

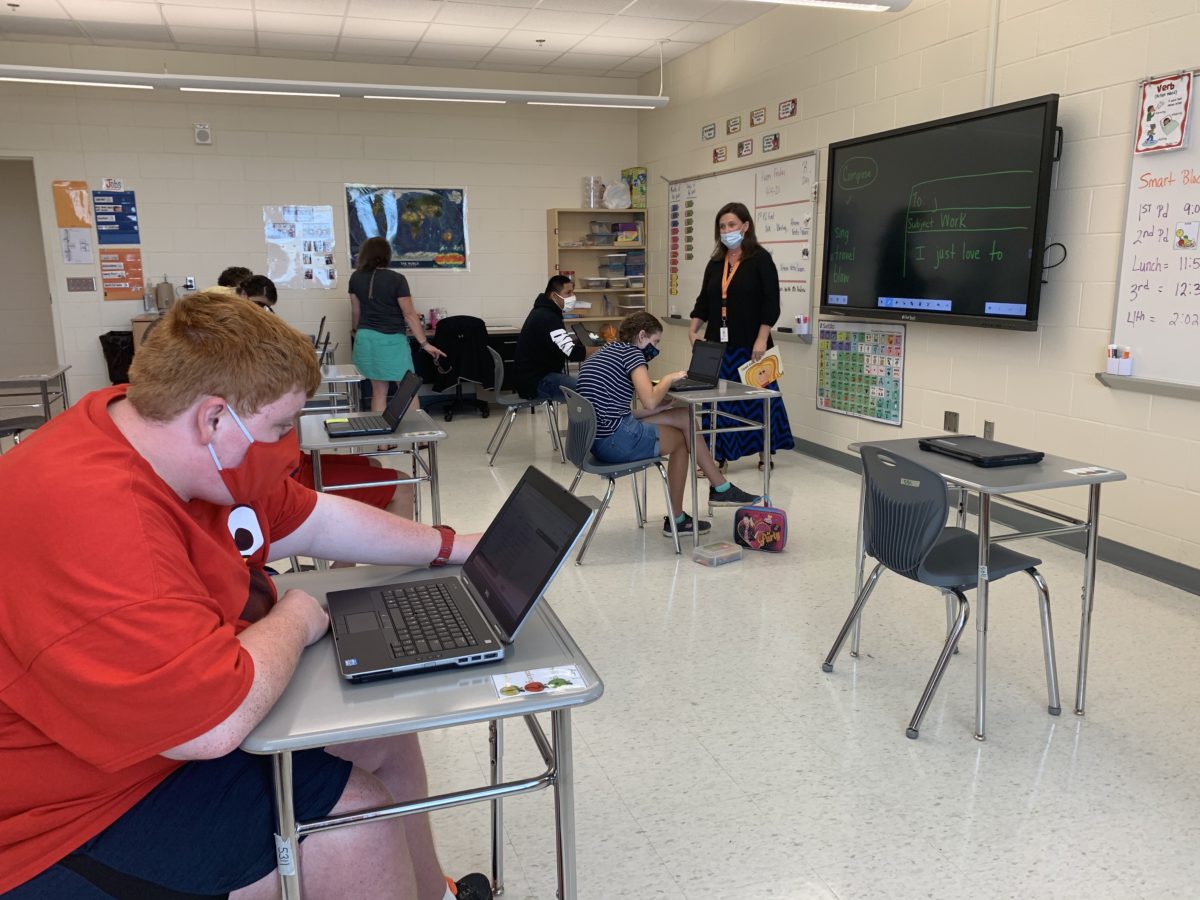

Across the hall, Annette Jenkins is reading a starter sentence to her kids.

“So our sentence starter is, ‘I just love to’” she says. “What are some action verbs we can use?”

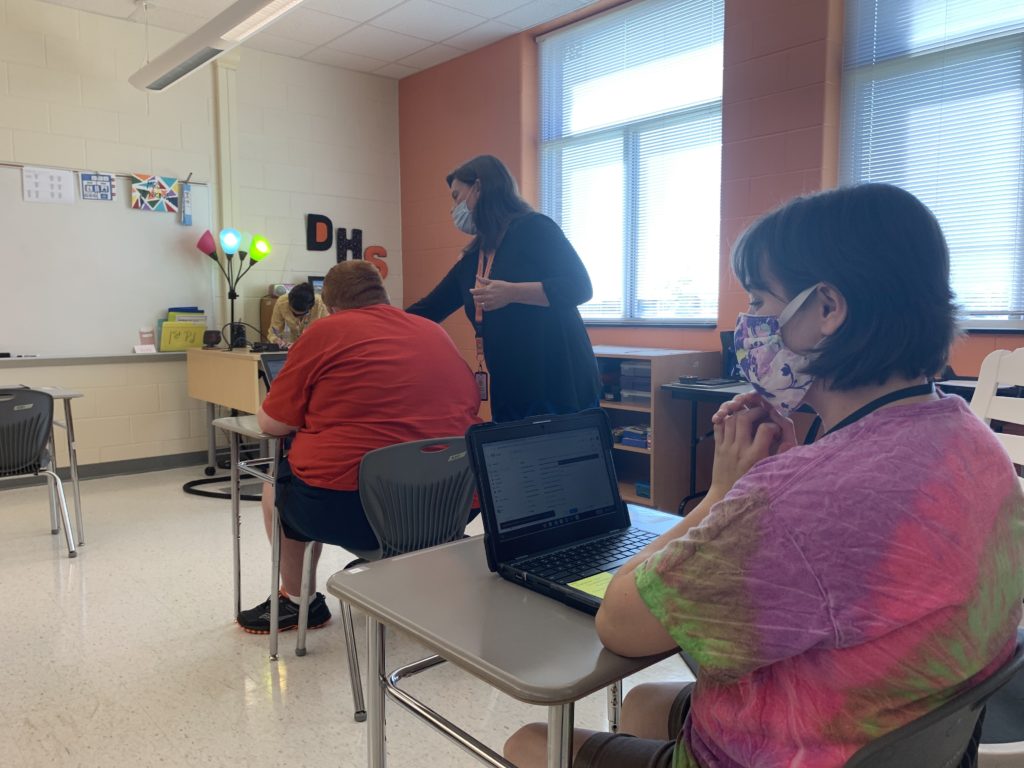

Like many students these days, these kids are sitting at computers. They are getting instruction from Jenkins and two aides who are roaming around to give individual support.

“Sing!”

“Blow bubbles!”

The verbs come rolling in.

“Great!” Jenkins says. “Now, normally we would write these, but since we are practicing emails, you are going to compose this in your email and you’re going to send all your work to me within this email.”

The kids are learning this lesson for a specific reason. Custer, watching from the back of the room, learned why earlier: “If we go into all virtual again,” an elementary teacher told her, “they need to be able to send me an email. They need to be able to communicate with me, and that didn’t happen as effectively before.”

Jenkins fixes on Hayden, who is in this class.

“I just love to,” she says, repeating the starter sentence. “What do you love to do, Hayden?”

“Vacuum,” Hayden responds as the adults in the room break into a loving laughter.

‘It is priceless’

Hayden Moore is often talking about vacuums, so his class loved hearing his sentence: “I just love to vacuum my house.”

Hayden used to be afraid of vacuums, so his parents started exposing them to him more to help him conquer the fear. They would stalk Oreck stores and let him look at the vacuums through the window. After time, they would take him inside. Soon, Hayden would turn them on.

He has become obsessed. Now he watches old QVC Oreck infomercials on YouTube and has them memorized. In fact, the family vacations near Myrtle Beach and has gotten to know the owner of an Oreck shop there. She put Hayden in one of her ads. She also suggested to the family that Hayden might make a good vacuum repairman when he’s done with school.

His mom relays the story as she talks about the importance of Hayden getting the services he needs right now. He needs them to grow toward an independent livelihood.

She thinks back to the spring when she told him he couldn’t go to school.

“There was a lot of repetitive asking why and, also, you know, he missed his classmates, he missed his teachers,” she said. “As a parent, no matter how hard you try to have that routine and structure, it’s just not the same as being in the school building.”

With Hayden back now in school now, he’s totally different.

“The routine is different, but he still has his routine,” she said. “It is priceless.”

Recommended reading