Gustavo Soto was a standout student at Monroe High School, finishing seventh in his class of 254. He’s a math whiz with a sharp mind. For many students with his grades and aptitude, the decision among which colleges to attend would be a tough one. For Soto, however, finding any college he could attend was the tough part.

“When I talked to [my guidance counselors], they said there’s nothing that I can really do,” he said. “That the only alternative was community college.”

That’s because Soto is an undocumented immigrant. His parents came into this country illegally while Soto was very young — even before he was of kindergarten age. He has attended North Carolina public schools for his entire K-12 education and has excelled. But after high school graduation, the UNC System schools felt out of reach. That’s because as an undocumented graduate, he is not eligible for in-state tuition.

“And most scholarships require you to be a citizen,” he added, “so most scholarships are really hard to get.”

Soto was determined to continue his education, and he is now enrolled at Central Piedmont Community College (CPCC). But the cost of out-of-state tuition there is about four-times what he would pay in-state — roughly $9,000 versus $2,400. To cover the expense, he returns to Monroe in the mornings to work as a math tutor for current students.

When he’s done there, he rushes to CPCC and takes a full load of classes. Afterward, he stays on campus to study and finish homework. It’s a full day. By the time he sees his home again, it’s time for bed. He wonders how long he can keep it up. And he also worries about whether the money will run out.

Soto doesn’t make enough from his math tutoring to cover his full slate of classes, but he’s a recipient of a Golden Door scholarship that helps him this year. He’ll have to reapply next year.

“If I do well, hopefully it continues and they can help me transfer to a four-year school,” he said. “There’s hope. I’m hopeful.”

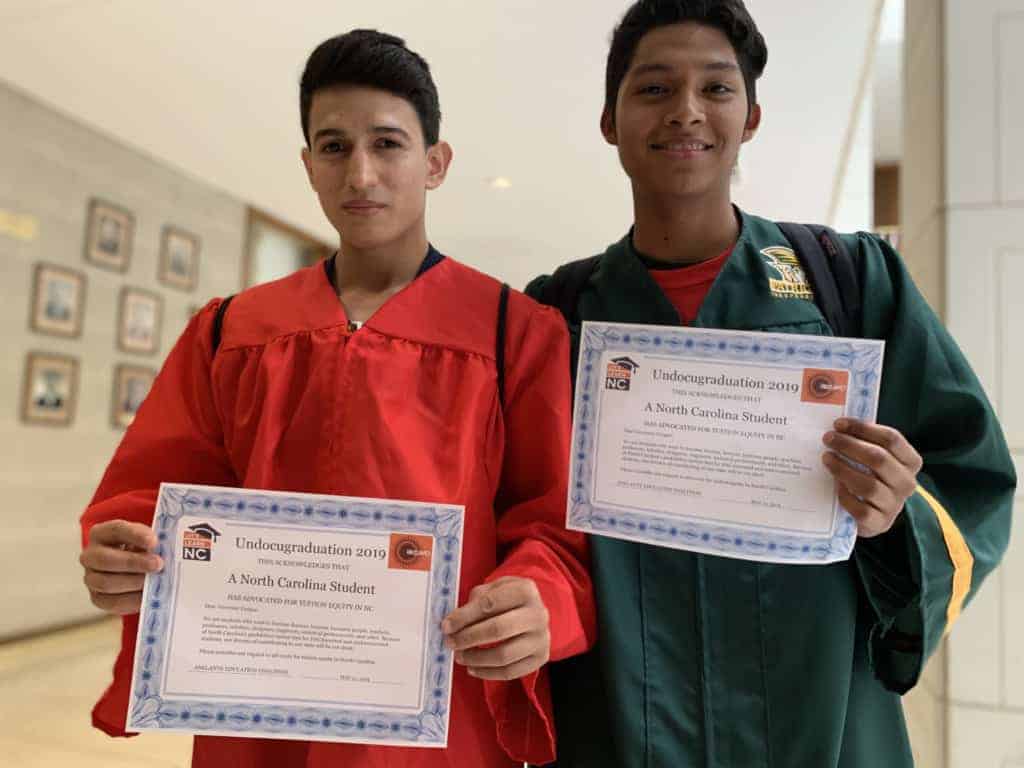

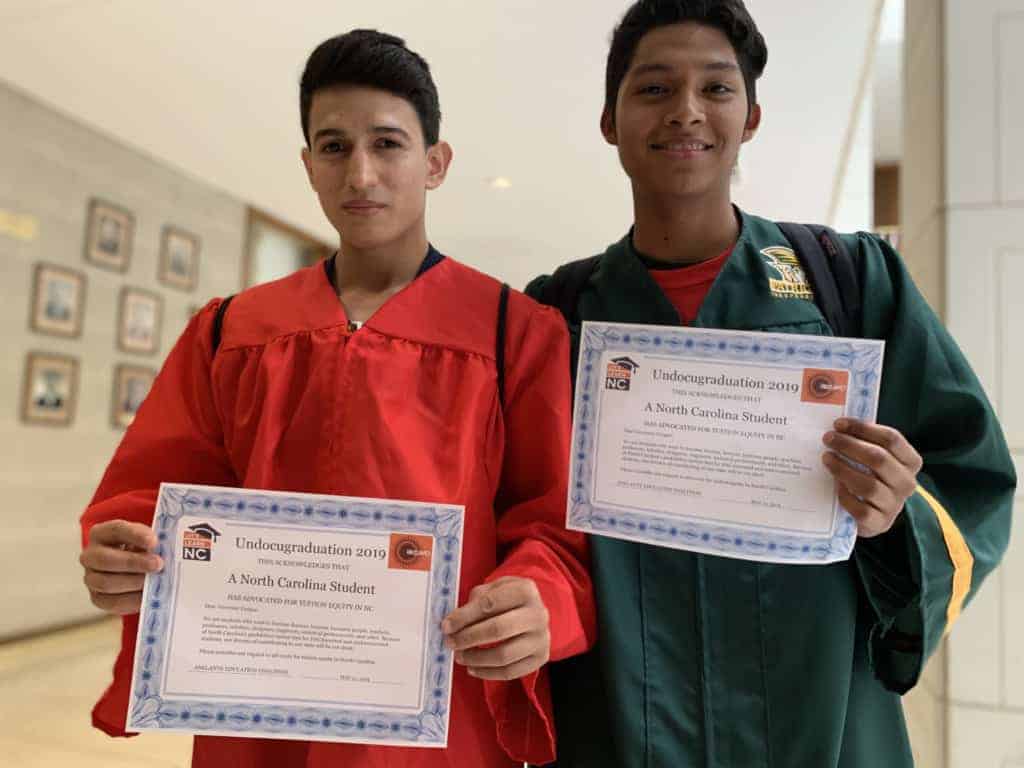

Soto was one of dozens of students and advocates who visited the state capitol on Wednesday for “UnDOCUgraduation 2019” — an event organized to call attention to the thousands of undocumented students who graduate North Carolina high schools but hit challenges in continuing their education, including having to pay higher out-of-state tuition rates.

The higher tuition is often an insurmountable obstacle. For most, like Soto, it means they cannot consider UNC System universities and focus instead on community colleges. But for many, unlike Soto, there aren’t scholarships or grants to help, so even community college can become unaffordable.

“Without the Golden Door scholarship, it wouldn’t be possible for me,” said Soto, who is eligible to be a Golden Doors Scholar because he is a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) student. “It gives me a big boost.”

There are more than 300,000 undocumented residents in North Carolina, along with 27,000 DACA recipients. Nationwide, an estimated 65,000 undocumented students — children born abroad who are not U.S. citizens or legal residents — graduate from high school each year. Many of them were brought to America as very young children when their parents entered the country. Only 5 to 10% of these undocumented graduates enroll in college.

This is happening while the state — and country — grapple with a growing workforce gap. According to a report by the Georgetown Public Policy Institute, 65% of jobs in the U.S. will require some form of education beyond a high school diploma by next year. Another report posits that, at the current production rate, the U.S. will lack five million workers needed to fill those jobs.

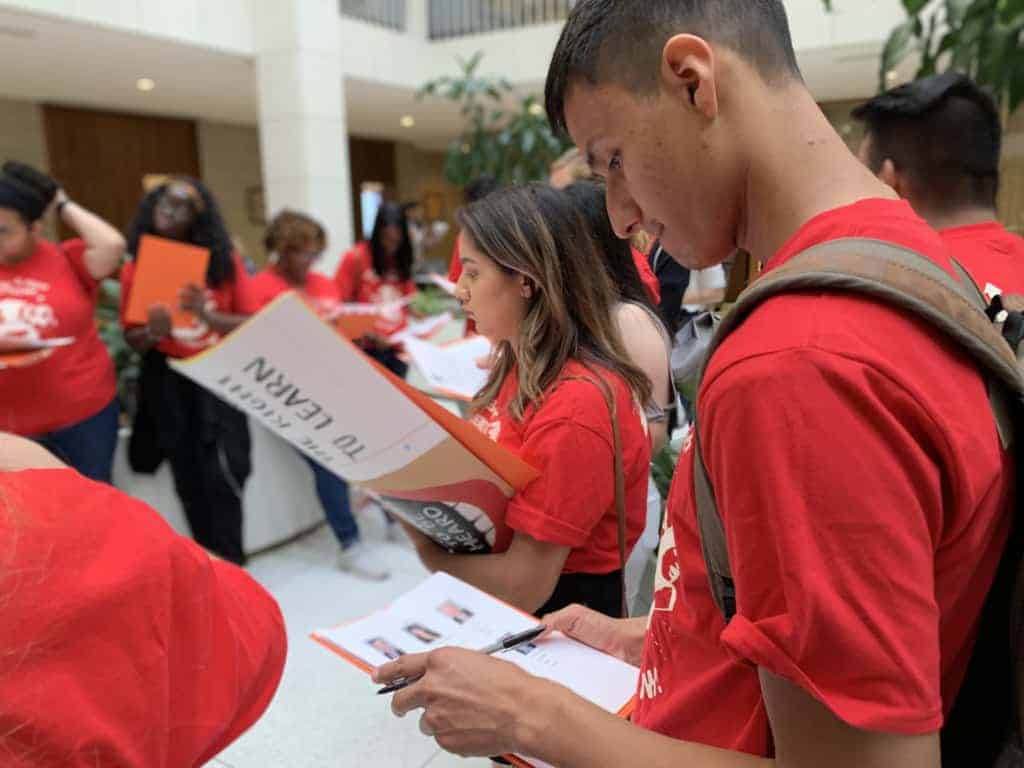

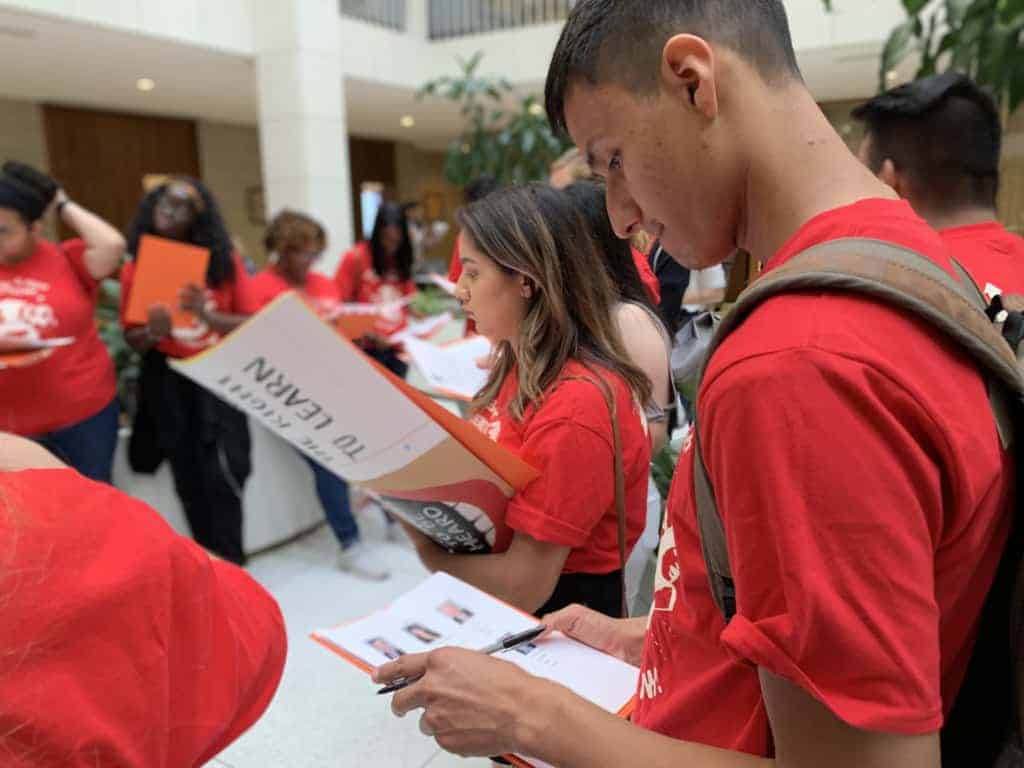

But the undocumented graduate market remains untapped, and advocates from eight groups — including Students for Education Reform and El Pueblo — want to change that. They are lobbying for in-state tuition equity for all graduates of North Carolina high schools, regardless of citizenship status. Both the state House and state Senate proposed such bills this legislative session, but they have no chance of becoming state law this year because neither crossed over to the other chamber prior to the mandatory cutoff date last week.

Meanwhile, 20 other states have passed in-state tuition equity laws, including Oregon. In fact, Oregon moved to tuition-free higher education in 2015 and, in keeping with treating undocumented students the same as in-state students, they extended the benefit to them, as well.

“This was about justice, fairness, and keeping faith with students for whom we’ve provided a K-12 education,” said Ben Cannon, executive director of the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission. “It’s arbitrary and unfair to say that now you’re 18, so public support for education disappears.”

To be clear, this is about practical access, not reversing a prohibition. North Carolina does not exclude undocumented immigrants from its state universities, independent colleges, or community colleges. However, it does have residency requirements for receiving in-state tuition which effectively leave undocumented students with the substantially higher price tag for continuing their education.

Some are fortunate recipients of Golden Door scholarships, like Soto. Others can be even more fortunate and find full scholarships, like Carlos Santos. He is a DACA student, making him eligible for Michael Jordan’s Wings Scholars Program, which offers him a full ride to a four-year university of his choice.

But the majority of undocumented students receive no financial help — like Santos’s brother, who attended one semester at CPCC before running out of money. He is now working as a cashier at a local bank.

“I don’t really think he has the mindset of furthering his education — just because of the limits and the obstacles,” Santos said. “It’s really hard to push through everything, and especially if you don’t have one of the scholarships. It’s a lot you have to go through, and some people just can’t.”

Santos is talking about that practical barrier versus technically having access. He and his brother are in very similar situations in terms of family background and immigration status. But Carlos is one of the fortunate few with a scholarship, and that gives him a boost.

“I never thought in a million years that my tuition and room and board would be paid for,” he said. “So now, I want to help the ones that don’t have this exact opportunity that I do.”

On Wednesday, that help came in the form of visiting the General Assembly to meet with elected state officials, including Senators Jay Chaudhuri, D-Wake; Wiley Nickel, D-Wake; Joyce Waddell, D-Mecklenberg — and Representatives Becky Carney, D-Mecklenberg; Wesley Harris, D-Mecklenberg; Pricey Harrison (whom another representative called the longest-standing supporter of in-state tuition equity in the assembly), D-Guilford; D. Craig Horn, R-Union; Rachel Hunt, D-Mecklenberg; Graig R. Meyer, D-Orange (who helped create this event); and Marcia Morey, D-Durham.

In meetings, the students introduced themselves and many shared their personal stories — which included being told by counselors that there were few options for them, or trying to attend post-secondary schooling by paying out-of-state rates before running out of money. Others talked about the fear of attending public institutions during the current climate on immigration, as U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests and deportations are on the rise under the Trump Administration, including in North Carolina.

Many legislators empathized. Some encouraged the students and predicted a change in the laws sooner-than-later. But most had one message of advice for students seeking change.

“You’ve got to keep doing what you’re doing now,” Horn said to a group of students in his office. “You’ve got to keep visiting us and keep talking about your situation. We hear from so many people and so many groups, there’s a lot that’s happening here everyday. If you want change, you have to make sure your voice is heard.”

For many of these undocumented students, however, life looks like school and work — and then sometimes more work when multiple jobs are needed to cover out-of-state tuition or just to help out with family expenses. Frequent trips to Raleigh, particularly when a majority of the group came from Mecklenberg and Guilford counties, is not realistic.

“I will try,” Soto says about a return trip to the capitol. “Right now, the semester is over so I came. When it starts, though, it would be hard.”

The day ended on a note of hope and inspiration, though. Students, many dressed in caps and gowns, took turns at a microphone to announce where they were in school and what they dream of doing afterward.

Social worker. Dental Hygenist. Pediatrician. Construction. Welder. Psychologist. Soto takes the microphone: “Math teacher.” He’d be a great one, too, his friend says as other students walk to the microphone. Police officer. Criminal law attorney. Nursing assistant. Public health.

The list of hopeful careers was long. And as they were announced, Carney, Chaudhuri, Harris, Nickel, Meyer, and Morey applauded and shook hands with the students. Meyer hands them a “diploma.” At the end of the day, all of the diplomas were stacked neatly and delivered to the Governor’s Mansion as the afternoon waned.

It’s been a long day, but as they make the walk to the Governor’s, Gia Claybrooks still has her energy up. She is a lead organizer for SFER. Before that, she was in the Peace Corps working with children in Guatemala. That experience is what pushes her to fight for in-state tuition rates in North Carolina.

“Just seeing from the other side, what people are leaving from and understanding their dreams and their hopes to have a better life by coming to the States and really work hard to have a better life and provide for their families, it really inspired me to get involved with justice work here,” Claybrooks said. “The best-case scenario is that students are able to graduate from high school knowing they won’t have to struggle and work three times as hard to graduate college.”