When school buildings closed in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, school nutrition departments across North Carolina pivoted quickly. Within just 48 hours, they rolled out new ways of offering meals to students, from curbside pickup to delivery on school buses.

At that time, an estimated 60% of students in North Carolina’s public schools depended on the meals they received every day at school.

That’s according to Lynn Harvey, director of school nutrition and district operations at the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI), who spoke during this week’s 10th annual NC Child Hunger Leaders Conference. The conference’s theme this year? Pivoting to the future.

“‘Pivot’ is the perfect word to describe what’s transpired over this year,” Harvey said. “So many conditions have changed — the federal regulations have changed, the food products have changed, delivery models have changed, staffing has changed … But one thing has not changed: Our genuine desire to feed kids.”

Addressing hundreds of virtual conference attendees, Harvey reflected on some of the numbers that describe how school nutrition departments have pivoted to adapt to the pandemic, including:

- 74: The number of federal waivers requested and received by the state of North Carolina from the U.S. Department of Agriculture since March 2020 that allowed schools to use a wide variety of delivery strategies, among other things.

- 3,223: The number of meal sites throughout the state.

- 21,000: The number of school buses that were converted to food trucks to deliver meals at the height of the pandemic.

- 500,000: The average number of meals served to children every day during the first 90 days of schools closed.

- 75 million: The number of dollars appropriated by North Carolina’s General Assembly to support school nutrition programs during the pandemic.

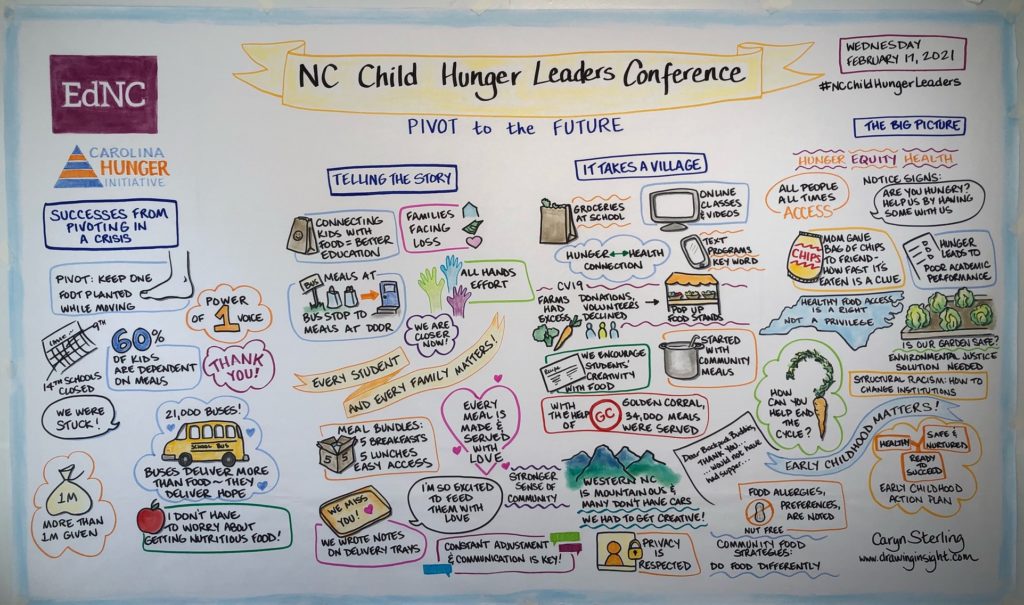

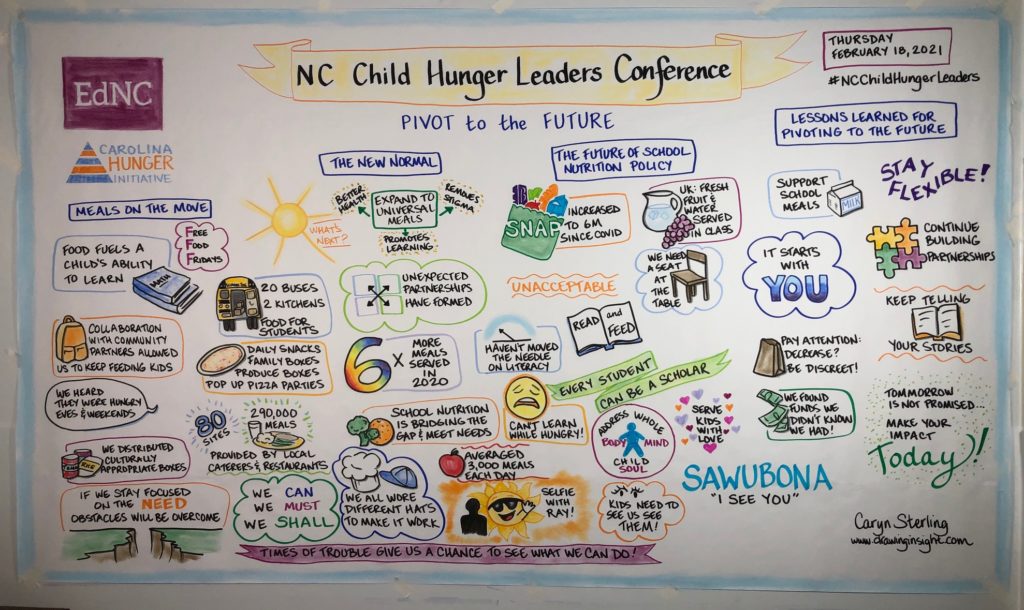

Hosted by the Carolina Hunger Initiative, the conference took place on Feb. 17 and 18. The agenda covered a variety of topics related to school nutrition programs, including the pivot to serving meals amid the pandemic, what’s to come for school meals in summer 2021, and more.

Click here to watch a recording of the first day of the conference, and click here to watch a recording of the second day. Below, view graphic recordings of the conference from Caryn Sterling.

Pivoting to meet the needs of students

“We all have had to pivot. We’ve all had to do some things a little bit differently to better serve our students. And it required all of us,” said Kisha Clemons, 2020 NC Principal of the Year and principal at Shuford Elementary School in Newton-Conover City Schools.

Clemons went on to describe the ways her school collaborated across departments — from bus drivers to office staff to child nutrition staff — to bring students meals in new ways.

One of the first strategies her school deployed was offering meals via school buses. When students came back to school last fall, they began offering breakfast in the classroom and lunch carts to increase the number of students that participated in school meals. And for students learning remotely, the school offered curbside pickup — and everyone from school board members to high school coaches pitched in to distribute the meals.

Melody Howell, school nutrition manager at Bethel Elementary School in Watauga County Schools, said her goal every day is to feed and nurture students, regardless of what challenges COVID-19 brings. Among other things, that meant dressing up in costumes during curbside pickup and writing personalized messages on to-go meals.

Beyond meeting the nutritional needs of students, Howell also discussed meeting their social and emotional needs through strong relationships.

“I also want to give them the love, support, and encouragement, and make a difference in their lives,” she said. “I want each child to know that they are loved and that I am so excited to feed them breakfast and lunch every day.”

The pivots described by Clemons, Howell, and many others during the conference resulted in schools across the state serving more than 130 million meals to students since the pandemic began, according to Harvey.

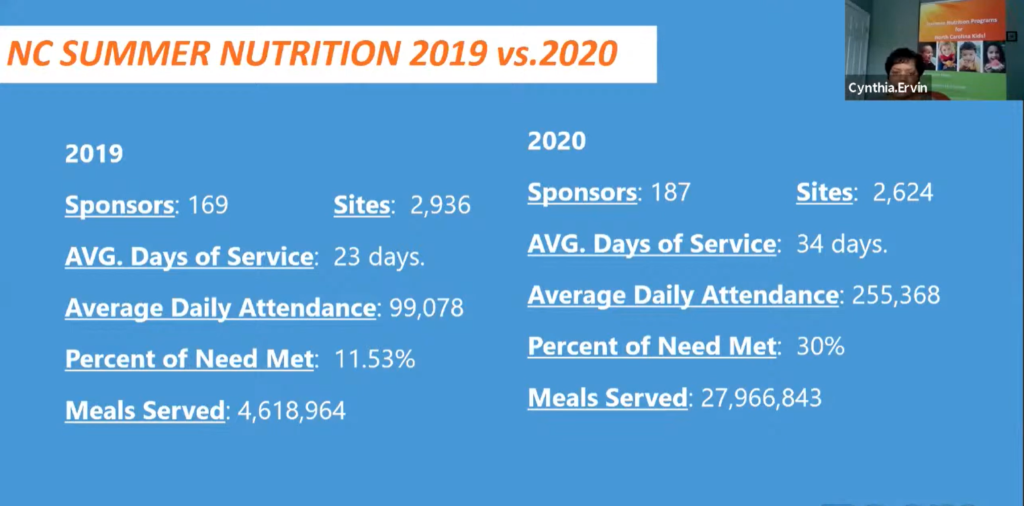

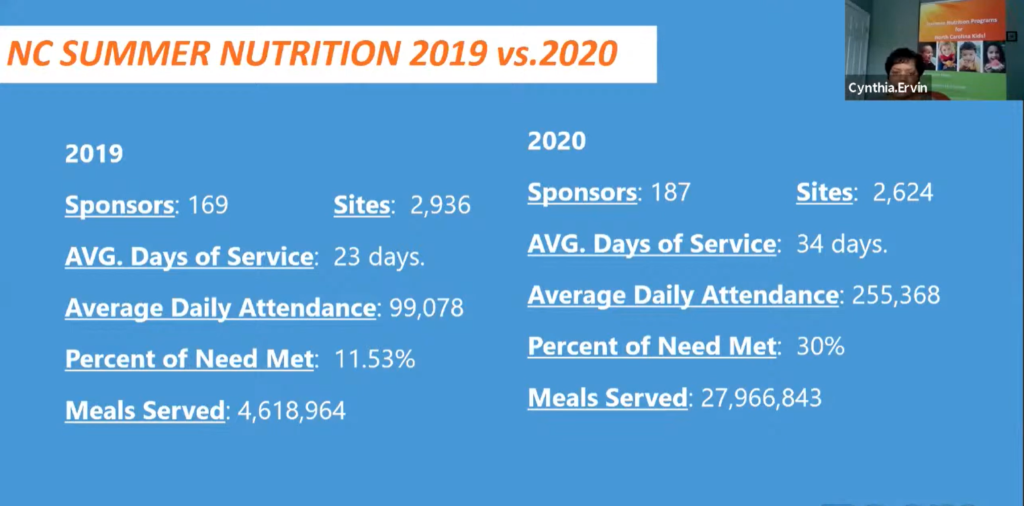

Cynthia Ervin, summer and special nutrition program assistant chief at the state Department of Public Instruction, spoke specifically about the progress made on serving summer meals in 2020.

In the summer of 2019, schools served roughly 4.6 million meals to 99,000 students, which met about 11.5% of the need. That figure is calculated by comparing the number of students who are eligible for free- and reduced-price school meals with how many of those students actually received summer meals.

But in the summer of 2020, six times as many meals were served to students — a total of 27.9 million meals to 255,000 students, which met 30% of the need.

The future of school nutrition

As schools look ahead to summer 2021 and beyond, what should they expect when it comes to school nutrition policy? Reggie Ross, president of the national School Nutrition Association (SNA) and a school nutrition consultant with the state Department of Public Instruction, outlined what SNA will ask Congress for this year.

The first request is universal school meals, or a permanent expansion of the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program to offer all students meals at no charge. Because of the pandemic, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has allowed free meals to be served to all students throughout the 2020-21 school year — and SNA wants to see that policy continue.

“We have proven that serving all students is not only accepted, but is needed to meet the needs of the students and the families that we serve,” said Ross, adding that universal school meals will eliminate the stigma and barriers that may prevent students from accessing needed meals.

Other SNA legislative requests include additional emergency financial relief directly to school nutrition departments and a reduction in regulatory and administrative burdens.

“Our programs have been impacted by overly complex federal regulations which divert resources from the mission of serving students,” Ross said.

In the final panel of the conference, officials from the state Department of Public Instruction discussed their priorities when it comes to the future of school nutrition.

Catherine Truitt, state superintendent of public instruction, said her team will be focused on addressing literacy and reading proficiency this legislative session. But as she thinks about addressing reading proficiency from a systemic standpoint, nutrition is crucial.

“If students are hungry, if they are malnourished, then this work will be for naught — because our students cannot be the best version of themselves, let alone try to learn how to read, if they have empty tummies,” she said.

Truitt said that moving outcomes forward for all students starts with addressing the base of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: “It starts with nutrition.”

For more, read this Twitter thread for a recap of the first day of the conference, and read this Twitter thread for a recap of the second day.