Growing up, my family relied on food stamps to survive for a period. At the time, I admittedly felt some embarrassment about that fact, yet I found a way to use the foundation provided by that public assistance to achieve several important goals in life.

I recently learned that my story is similar to that of popular podcast host Joe Rogan, with whom I’d never imagined I shared much common ground. While our financial circumstances and political views differ drastically, our shared experiences with the public safety net show how vital a resource it is families experiencing financial strife and adversity — across all lines of difference.

That shared experience between us and so many others underscores why I am seriously concerned about the recent budget bill passed by Congress and signed by President Trump, which will threaten programs like Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistant Program (SNAP) benefits for many Americans. As Democrats and Republicans discuss the far-reaching toll the bill could take on the American people, I can’t help but think about the implications for schools and the people who run them: principals and assistant principals.

Related reads

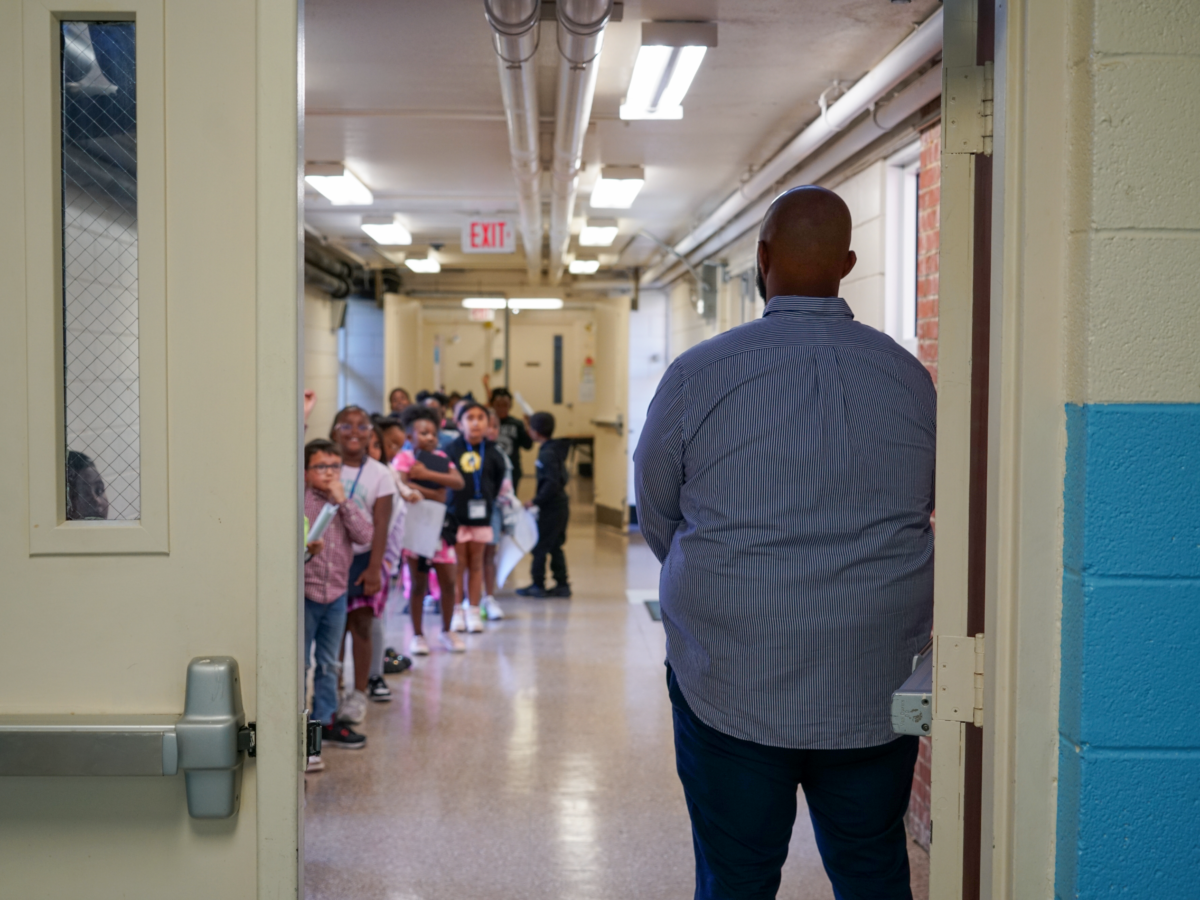

Principals and assistant principals are often asked to deal with crises in schools ranging from paper shortages to devastating gun violence. On a day-to-day basis, these leaders are engrossed with tasks that directly involve children and families, some who rely on the very benefits Congress agreed to drastically cut. These decisions only add to the running list of external factors that complicate running schools in the United States.

In North Carolina, roughly 1.4 million children rely on Medicaid and nearly 600,000 rely on SNAP benefits. For children attending schools in every community, but especially low-wealth communities, changes to these programs could have devastating ripple effects. Health and nutrition are deeply tied to outcomes like attendance, academic performance, and engagement.

Principals in North Carolina are compensated based on their school’s size and ability to show growth on academic metrics. As our federal government shifts away from protecting the basic needs of our most vulnerable — children — it is time for a new metric that considers the complexity of leading schools that are constantly asked to do more with less.

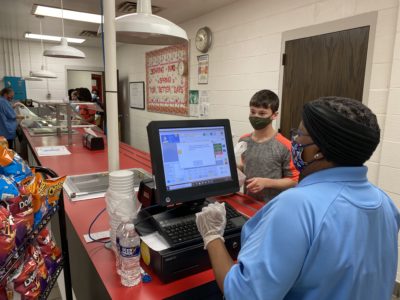

According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, nearly 60% of children in North Carolina were eligible for free lunch during the 2019-2020 school year, which translates to about 900,000 children. One way that children can qualify for free school lunch is tied to their eligibility for SNAP benefits. The legislation states that a portion of funding for SNAP benefits will be shifted to states. There is no guarantee, however, that states will be able to shoulder this cost, and states may eventually need to cut benefits or change eligibility requirements. This could mean that children who once benefitted from SNAP could lose their automatic eligibility for free school meals.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Even if policy plans are executed perfectly, and history has taught us that they won’t be, we can still assume that this will have resounding impacts on children and schools since neither are isolated from the collective challenges a community faces. Schools already deal with community issues like food insecurity and psychosocial problems like disengagement, which directly and indirectly impact children and families and make it more difficult for school leaders to do their jobs.

Organizations like the North Carolina Principal and Assistant Principals Association (NCPAPA) have been calling for legislators to consider how difficult it is to be a principal. Even before these changes, they’ve asked legislators to counterbalance an impending leadership shortage. According to NCPAPA, nearly 50% of principals plan to leave their roles in the next three years. Specifically, they have asked for the legislature to consider the complexity of a school, which includes a school’s size and characteristics of the students it serves — like housing status, income levels, and languages spoken — in hopes of retaining effective leaders. It takes an additional amount of resources and planning to run some schools, and leaders should be recognized for that.

Several years ago, I served as the director of community schools for a nonprofit in New York City public schools. I saw firsthand that school leaders do more than just oversee classrooms. They are often one of the first points of contact for families who are in need. These cuts impact everyone, including and especially our school leaders. If we must live with the changes, then it is time our lawmakers recognize and support leaders in the incredibly multifaceted role they play.

Recommended reading