|

|

In 1965, the year I graduated from high school, the Beatles sang of “nowhere man.” The next year, the Beatles asked in song, “All the lonely people, where do they come from? … Where do they belong?”

Now, as then, schools exist in, and respond to, the culture and economy of their time and place. Today’s middle and high school students have had their education disrupted by a pandemic, feel stressed by academic pressure, grow anxious over job prospects, live in an increasingly multi-ethnic society, fear the eruption of firearms, and cling to social media that both connects to the world and whips up misinformation and hate.

Recent research examines worrisome trends in adolescent well-being and economic prospects, producing findings that address two parallel questions: What’s the matter with girls? What’s the matter with boys?

Looking at trends from 2011 to 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) hail reductions in risky sexual behavior, substance abuse, and bullying at schools. And yet, says the CDC report, “experiences of violence, mental health, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors worsened significantly.”

The CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey drew its findings from 99 questions posed in 2021 to more than 17,000 students, both boys and girls, in public, charter, and private high schools across the nation. The report provides data on LGBQ+ students, as well as differences among racial and ethnic groups.

Its headline-grabbing finding is that “female students are faring more poorly than male students.” The CDC reports that nearly six in 10 teenaged girls say they have felt persistent sadness or hopelessness — and nearly one in four have made a suicide plan. Almost two in 10 female students experienced sexual violence.

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, noting that he is the parent of two teenagers, called the CDC findings “alarming.” The Washington Post reported the story under the headline: “The Crisis in American Girlhood.”

Over the past year, Richard V. Reeves, a senior fellow in economic studies at The Brookings Institution, has produced a torrent of essays and published a book arguing for efforts to bolster the prospects of young men. His book title is “Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do about It.”

Among high school students, Reeves reports, boys account for two-thirds with the lowest grades and only one-third with the highest grades. He calculates that 88.45% of girls graduated on time in 2021 compared to 81.9% of boys.

“In 1970, just 12% of young women (ages 25 to 34) had a bachelor’s degree, compared to 20% of men — a gap of eight percentage points,” Reeves writes. “By 2020, that number had risen to 41% for women but only to 32% for men — a nine percentage–point gap, now going the other way. That means there are currently 1.6 million more young women with a bachelor’s degree than men.”

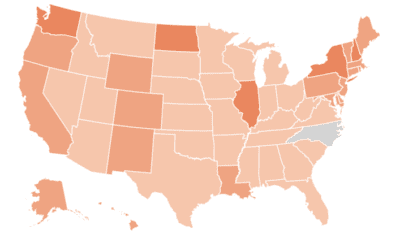

In North Carolina, according to Reeves’ state-by-state chart, 39% of women 25 to 34 years of age have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 30% of men.

“Male employment has not fallen because men have suddenly become feckless or work-shy,” Reeves writes, “but because of shifts in the structure of the economy. Male jobs have been hit by a one-two punch of automation and free trade.”

Reeves calls on states to establish a commission on men and boys, akin to the North Carolina Council for Women and Youth Involvement. More boldly, he advocates expanding so-called “redshirting” of young boys by delaying their entry into school by a year. While acknowledging that his proposal would strain the preschool care systems, Reeves argues that “boys should start school a year later than girls, on the grounds that on average they mature more slowly.”

In its report, the CDC cites school connectedness and parental monitoring as key “protective” factors for adolescent well-being. It recommends quality health education and connecting youth and families to community services.

“Supporting schools in efforts to reverse these negative trends and ensure that youth have the support they need to be healthy and thrive will require partnership,” says the CDC, which goes on to declare that “every adolescent deserves to go to a school that gives them the knowledge and skills they need to make healthy decisions; have access to the services they need; and feel safe, supported, and included.”

Artists of the caliber of the Beatles give expression to the culture of their generation and often point to its fragilities. It’s the less celebrated but essential work of educators, school administrators, and public officials to shape and sustain schools that “every adolescent deserves.”

Recommended reading