|

|

Lessons from the past school year. Plans for the year ahead. For EdNC’s Special Report, we asked leaders to share how the pandemic impacted education & what that means for the future. Read the rest of the series here.

Alarm bells are ringing loudly about the long-term effects of disruptions to learning and work during COVID-19. As we emerge from the pandemic, compelling data indicate we need a Marshall-type recovery plan for work and education in North Carolina. The plan must constitute a serious effort to stimulate production and promote stable economies in all counties, as well as offer a meaningful focus on:

- Existing workers with low skills.

- Former workers who left the labor force during COVID-19.

- Students in K-12, especially those who were already underserved.

- Our youngest residents, ages birth through 5.

Even before COVID-19, we knew the majority of new jobs being created in North Carolina would require more education than a high school diploma. We knew also that was an attainment level of less than half of North Carolinians ages 25-44. If COVID-related closures caused damage to students’ academic progress and increased the numbers of adults leaving the workforce, we will have compromised the state’s “2 million by 2030” post-secondary credentials goal and our state’s future economic growth may pay a price.

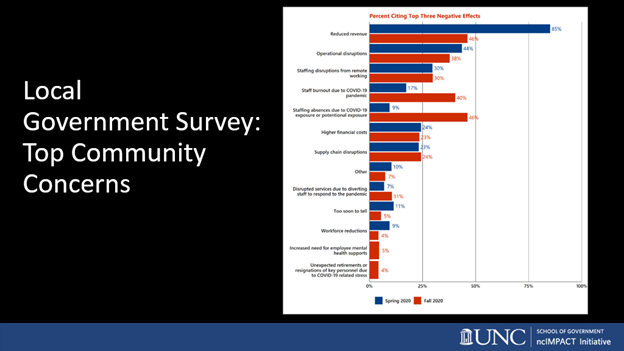

The alarm bells are reflected in responses to two 2020 surveys of local government leaders in North Carolina. The responses make clear that employment and learning are top of mind for local leaders.

First, let’s start with immediate-term work. We must offer meaningful opportunities to upskill existing workers to offer them and their families a chance to thrive.

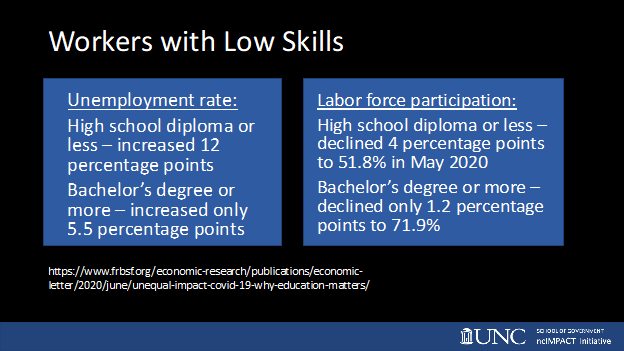

Unemployment for workers who hold a high school diploma or less increased more than double the rate of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher (12% versus 5 ½%) during the early months of COVID-19.

It is important to note here that unemployment rates refer to those people who are actively looking for a job. Labor force participation rates, on the other hand, are the number of people seeking work or working, as a percentage of the total population. This participation rate helps us see changes in the numbers of people who have just given up looking for work. In May of 2020, those with a high school diploma or less who were actively engaged or trying to be engaged in the labor force declined by four percent to 51.8%. Labor participation rates for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher declined only 1.2 percent during the same period and ended at 71.9%.

Many of the low skill jobs lost have returned. Others, especially in hospitality and tourism, will return as states continue to relax COVID-19 restrictions. However, many workers who lost or left their jobs will need to be upskilled if they are to have more resilience in the next economic downturn. Our state’s approach to workforce development must take into account this issue of resilience to economic shocks offered by postsecondary credentials.

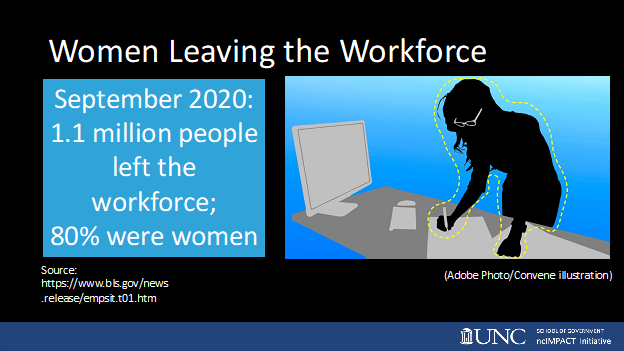

Second, women left the workforce in disproportionately high numbers during COVID-19.

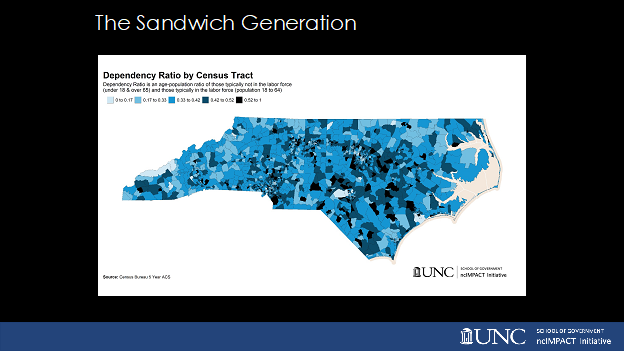

There is little doubt that the circumstances of the pandemic intensified pressures for working women. Many had to stay home to care for school-aged children when schools went to remote learning. Others were left with caregiving for young children whose child care centers closed or elderly family members rendered particularly vulnerable during the pandemic. As noted below, dependency ratios vary across the state, but the number of women leaving the workforce indicates women are bearing the brunt of caretaking responsibilities.

The early days of our economic recovery may be a good time to provide learning opportunities for people, including the large number of women, who have left the workforce. This might be one way to ensure that we do not exacerbate an existing wage gap when women return to the workforce later at lower wages.

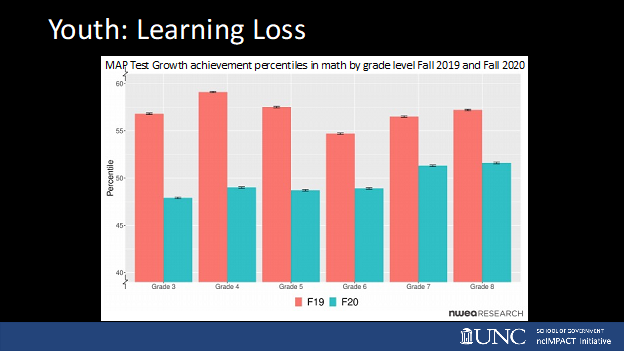

Third, we don’t know how much learning students have lost and it will be a long time before we know anything truly definitive. However, researchers have offered projections that paint a grim picture. The nonprofit testing organization NWEA predicts that students began this school year having lost roughly a third of a year in reading and half a year in math.

The graph above shows what has happened to math scores nationally. CREDO, an education research organization, more direly predicts that the average student lost 136 to 232 days of learning in math. Finally, the consulting firm McKinsey suggests that by the fall of 2021, students will have lost three months to a year of learning, depending on the quality of their remote instruction.

Not everyone agrees with the predictions. Of the CREDO study, Constance Lindsay, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Education said, “It’s hard for me to believe that somebody lost a year [of learning] in a quarter [of the year].”

The predictions are of great concern for all students, but we know that some will be more disproportionately impacted by learning loss. Underserved students have been even more underserved during the pandemic. We need an acceleration plan.

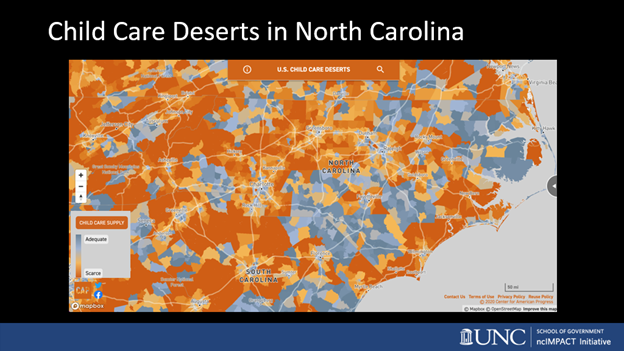

Finally, the early learning infrastructure is fragile. A recent article by the St Louis Federal Reserve Board revealed that more than 40% of child care workers who were employed in February 2020 — just before the pandemic took hold in the U.S. — were unemployed in April 2020, and total employment in January 2021 remained 20 percent below pre-pandemic levels. The map below offers some insight into the challenges for child care availability across the state. The blue represents adequate coverage. The dark orange represents scarcity.

The research is clear that high-quality early childhood development yields social returns in the form of better outcomes for children in the future, and disruptions to early childhood education can undermine those gains. It is also clear that the child care sector supports current economic activity by allowing parents (especially mothers), who want to do so, to participate in the labor market.

In conclusion, it may be hard to hear words of alarm at this moment of euphoria over announcements of Google and Apple expanding in our state. We have to face the fact, however, that COVID-19 has widened some already gaping chasms in our state. The good news is we have the “know-how” to develop a plan to respond effectively to the groups most adversely affected by the pandemic. Let’s put that Marshall-type plan into action.