North Carolina no longer holds one-day-only elections. The state has decisively shifted to an election period that runs from the start of early voting to the closing of polls on Election Day. Thus the period begins next Wednesday, Oct. 17 and ends at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 6.

For many North Carolinians, a basic act of their citizenship — voting — is only days away, not a month off. Without a heated statewide election to galvanize attention, the 2018 off-year elections for congressional, legislative, and judicial seats pose a challenge to citizens to become fully educated voters, or, if so inclined, “education voters.”

The General Assembly, controlled by a veto-proof Republican majority, declined to place a referendum on the ballot for voters to decide on a proposed $1.9 billion bond issue for school construction statewide. The proposal sought to go at least part of the way to responding to the 2015-16 facility needs survey that identified more than $8 billion in five-year needs for new schools, additions, renovations, and equipment.

In a sign of the times in the state’s geographical-political dynamics, Wake County asks its voters to approve slightly more than $1 billion in bond borrowing for public schools, community colleges, and parks and greenways. The schools’ portion comes to $548 million for construction, renovations, and equipment. Wake Tech would get proceeds of $349 million for expanding the RTP campus and for facilities especially for skilled trades and law enforcement training.

Wake, a county of more than 1 million people and two of the state’s 10 largest cities, has the fiscal capacity to finance such an array of capital improvements. It’s also a Democratic-governed county with an economy that attracts residents who want strong schools and appreciate amenities that add up to a high quality of life.

In contrast, North Carolina’s mid-size and small cities, along with rural communities, cannot match a major metro’s fiscal capacity, even stretching their property tax to the limit. While the legislature turned down a statewide school bond issue before two hurricanes hit the state, now several local school districts face even greater needs as they seek to rebuild.

Of the six constitutional proposals that Republican lawmakers placed on the ballot, one amendment has a special relevance to the future of education, though it doesn’t mention the connection. That proposed amendment would place in the Constitution a limit on the income tax rate — and in doing so, would put restraints on future governors and legislators in responding to educational needs of pre-K toddlers, children in elementary schools, teenagers in middle and high schools, and young adults in colleges and universities.

The state Constitution now limits the income tax rate to 10 percent. The amendment would drop the cap to 7 percent. Next year, the individual income tax rate will fall to 5.25 percent. The corporate rate has gone down to 3 percent. Since 2013, the Republican legislative majority has enacted a series of tax measures — including a flat-one-rate income tax — that has resulted in tax-burden shifts that favor businesses and the affluent more than middle- and lower-middle income households.

At the moment, a 7 percent rate may seem more theoretical than imminent reality. And yet, a constitutional provision has substantial long-term implications, as the voters’ guide issued by the State Board of Elections and Ethics Enforcement explained in low-key language:

“Income taxes are one of the ways state government raises the money to pay for core services such as public education, public health and public safety…Therefore, in times of disaster or recession, the state could have to take measures such as cutting core services, raising sales tax or fees, or increasing borrowing.”

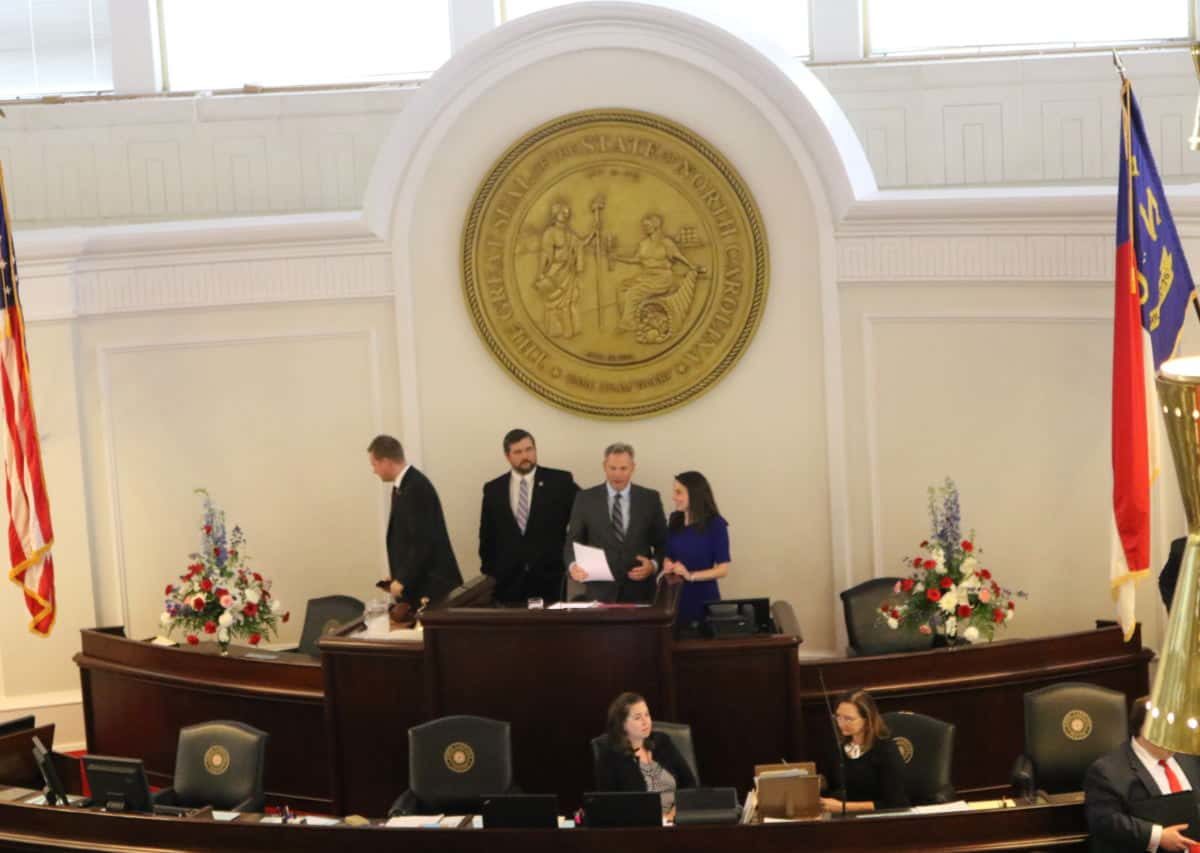

For “education voters’’ as early voting opens, the 2018 off-year elections appear perhaps as consequential as any since the Republican surge in 2010. Nationally, the focus of politicians and pundits is on how the outcome of disparate races for the U.S. Senate and House will embolden or constrain the tumultuous, break-the-norms presidency of Donald Trump. In this state, the elections for 120 House seats and 50 Senate seats — as well as referenda on Voter ID, judicial appointments, and the elections-ethics board composition — will affect the balance of power between the Republican-majority legislature and the Democratic governor.

Power and personality have crowded out policy as the defining elements of this election cycle. The centuries-old cliché holds that “to the victor go the spoils.” But it’s also true that to the victors goes power to make policy.

Recommended reading