|

|

Thomas Jefferson, the third United States president, a wealthy landowner with hundreds of enslaved people, the drafter of the Declaration of Independence with its proclamation that “all men are created equal,” founded the University of Virginia as a public institution in 1819.

As he awaited legislative adoption of his proposed university, Jefferson fretted in a letter written in the rather lax spelling standards of his time.

“My hopes however are kept in check by the ordinary character of our state legislatures, the members of which do not generally possess information enough to percieve the important truths, that knolege is power, that knolege is safety, and that knolege is happiness,” he wrote.

In 1776, as North Carolina made the transition from British colony to an American state, its Provincial Congress adopted a constitution with two education provisions. One allowed the legislature to establish schools — initially envisioning private, not public funding — “for the convenient instruction of youth.” And it authorized the establishment of a public University of North Carolina, subsequently chartered in 1789 and opened in 1795, two decades before Virginia’s university.

Now, two and a quarter centuries later, North Carolinians who lead and administer, teach in and advocate for, public education fretfully await the General Assembly to produce a budget in which schools, community colleges, and universities represent 60% of the General Fund. Not unlike Jefferson, they wonder whether today’s state lawmakers fully “perceive the important truths’’ about knowledge provided through public education institutions.

Customary commentary on power comes through a political-governmental lens: veto power, balance of power, checks-and-balances, veto-proof majority, and such. At the North Carolina General Assembly, a Republican super-majority has exercised its power by overriding the Democratic governor’s vetoes of several education-related bills.

In addition, Republican leaders have prolonged behind-the-scenes budget negotiations into September, leaving educators’ pay raises in limbo and district school officials scrambling to fill classrooms with teachers and to hire enough drivers for the yellow buses. Local school boards are also adopting implementation rules under the new “parents’ rights” law.

The Republican majority appears poised to approve a sweeping expansion of state subsidy for students in private schools, as well as lightening the hand of the state on public-funded charter schools. The budget will almost certainly contain further income tax reductions that would constrain the future flow of revenue with implications for public education funding in the decade ahead.

The current moment emphasizes that the familiar phrase, “knowledge is power,” remains as relevant today as when Jefferson used it at least four times in correspondence about founding Virginia’s public university. But of course, knowledge has expanded vastly since the early 19th century. What’s more, the rationales for and purposes of public education have similarly expanded.

The original imperative — to sustain democracy — rested on a fundamental insight that the nation must have citizens with competence in self-government. Today’s fractious politics, rife with disinformation and rejection of long-held democratic norms, cries out for robust education in history, civics, and leadership.

Out of the shift from an agrarian to an industrial society arose a new economic imperative. Across geography and party lines, a dominant North Carolina mindset has focused on stronger schools as an urgent need to produce more citizens with higher skills and to fashion a workforce attractive to businesses.

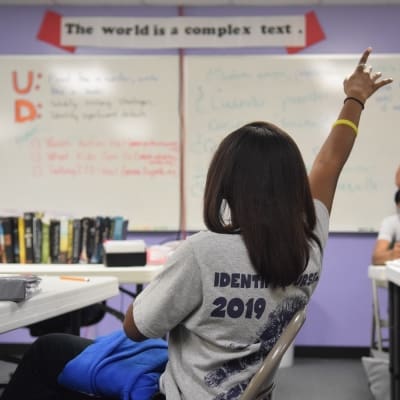

A good-life imperative for education recognizes that Americans are not only workers and voters, but also parents, consumers, spectators, worshipers, and neighbors. Knowledge gives individuals power to cope in a complex society requiring decisions on what to purchase, how to live healthy lives, and how to raise a family in an era of internet connections and artificial intelligence.

“Knowledge is power’’ is not only about politics. When North Carolina’s state and local authorities fall short of meeting the constitution’s mandate for “a general and uniform system of free public schools…wherein equal opportunities shall be provided for all students,” they in effect limit the power of many citizens to burgeon fully in modern society.

When the legislature finally calls an end to the current session, the state’s great education debate over clashing agendas will continue. North Carolina will remain in the long game of confronting accelerating societal and economic change with keeping-pace reforms in its sprawling, multi-layered, essential public education institutions.