“Never let a good crisis go to waste.’’ The Italian Prince Machiavelli reportedly said something like that, and so apparently did Winston Churchill. The old saying holds that a crisis opens up an opportunity, if a society and its leaders will grasp it, to build a stronger future.

For now, the coronavirus crisis has North Carolina school authorities, educators, and parents mostly focused on immediate challenges: feeding students in need, teaching students remotely, figuring out protocols for reopening schools when it’s safe to do so. Among policymakers, meanwhile, there is a sense that, as state Board of Education Chair Eric Davis said, “We know public schools are forever changed.”

But how? It’s too soon to draw definitive answers with lessons still to be learned as the public health and economic crises continue to play out. And yet, it’s not too soon to recognize that North Carolina has its own experience to draw on in mustering the political will and civic self-confidence to respond to a crisis.

Fresh evidence that North Carolina has demonstrated the ability to launch a creative school initiative and bring it up to scale arrived last week in research disseminated by The Brookings Institution. For 14 years, five researchers, including two from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and one from Research Triangle Institute, have conducted a rigorous study of North Carolina’s early colleges.

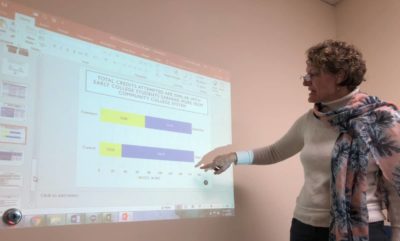

“The early-college model demonstrates that combining portions of high school and college is possible,” they write. “Our results to date show many advantages, including an increase in degree attainment and less time to degree, which should benefit the students who attend these schools as well as society more broadly.”

North Carolina’s early-college initiative originated in 2001, when the United States fell into a short and shallow recession. That downturn, combined with NAFTA and other free-trade treaties, pummeled the state’s textile industry. From 1997 to 2002, the state lost as many as 170,000 jobs in textiles and apparel. In summer 2003, the state was shocked when Pillowtex shut down five North Carolina plants and dismissed 4,000 workers in a single day.

At a moment when a civic understanding was growing that economic change would require more North Carolinians to continue their education beyond the 12th grade, Gov. Mike Easley convened a broad-based Education First Task Force in 2001, his first year in office. (Disclosure: I served on the task force.) Among multiple recommendations in its mid-2002 report, the task force called for the state to establish innovative high schools that could raise graduation and college-going rates.

After attending a follow-up roundtable to develop the idea further, Walter Dalton, then a state senator and now president of Isothermal Community College, sponsored legislation, enacted by the General Assembly, that set up an innovations fund. In 2003, the Gates Foundation approved $20 million in grants that led to the creation of the NC New Schools Project to start up innovative models of high schools.

In 2005, Easley won legislative approval for a set of initiatives, which he branded “Learn and Earn.” His early-college initiatives in particular focused on propelling lower-income and first-generation students into higher education. By the time Easley left office in 2009, the state had 70 early college high schools, most of them located with community colleges, a few with universities.

Now the state has 131 high school-college hybrids known as Cooperative Innovative High Schools, with around 28,000 students earning both high school and college credits. Most are early colleges, some middle colleges, some career academies. During her 2009-2013 term, Gov. Bev Perdue added another layer with the College and Career Promise program to give students in traditional high schools access to post-secondary courses. Add in magnet schools and public-funded charter schools, and it’s evident that high schooling in North Carolina is not a one-size-fits-all enterprise.

Over the past two decades, the expansion of innovative high schools has proved durable through both Democratic and Republican rule in state government. The development and expansion of these schools resulted from an agreed upon need to increase the number of North Carolinians with two- and four-year degrees and to heighten the competitiveness of the state’s workforce. This agreement spawned collaboration across the separate systems governing public schools, community colleges, and universities. Lessons include the importance of research-based design and of coalition building in both public and private sectors — and that political leadership matters.

The point here is not to hold out early colleges as a silver bullet in school reform, though they have expanded opportunity for thousands of young North Carolinians. Rather, it is that policymakers and citizens can learn and gain self-confidence from their own state’s recent experience in making the most of a crisis as they confront the possibility that COVID-19 changes everything.

(See also EdNC’s extensive reporting on Cooperative Innovative High Schools here.)