|

|

In recent years, tiny bits of plastic have become one of the hottest topics in environmental science. I was unaware of them until my middle school science class viewed a documentary about how microplastics, caused by the degradation of larger pieces of garbage in the ocean, were causing problems for marine life, which led to problems further up the food chain.

At the time, the concept of microplastic pollution seemed distant; it was not something I had to worry about living in the pristine mountains of North Carolina. That perspective quickly changed when I conducted a research project in tenth grade through the TIME 4 Science research program.

Are microplastics in the Little River?

My project involved taking various samples to measure the quality of the water in a local river. Two sites along the Little River, which feeds into the French Broad, were chosen for sampling. The upstream site used in my research was located in DuPont State Forest, near the headwaters of the Little River.

To many, including my family and myself, that is a place where some of the world’s purest water can be found — cool, clean, and straight from the mountain. At the start of my project, I did not expect to find a single microplastic.

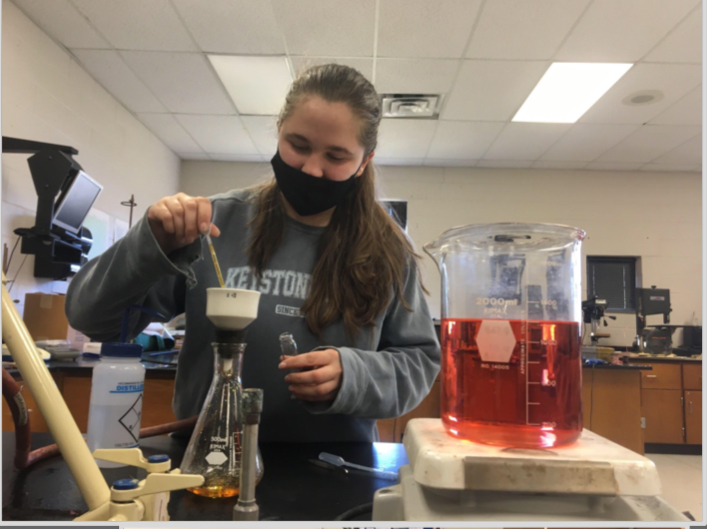

The first set of tests was a chemical analysis to establish a baseline between the two sample sites on the river. The results showed no significant difference between the two sites except for conductivity. Next, the SMIE (Stream Monitoring Information Exchange) sampling method for benthic macroinvertebrates (BMIs) was used to determine the quality of the water. This consisted of one kicknet sample, one leaf pack sample, and one washbucket sample. A statistically significant difference between the two sites was found, with the water quality decreasing downstream.

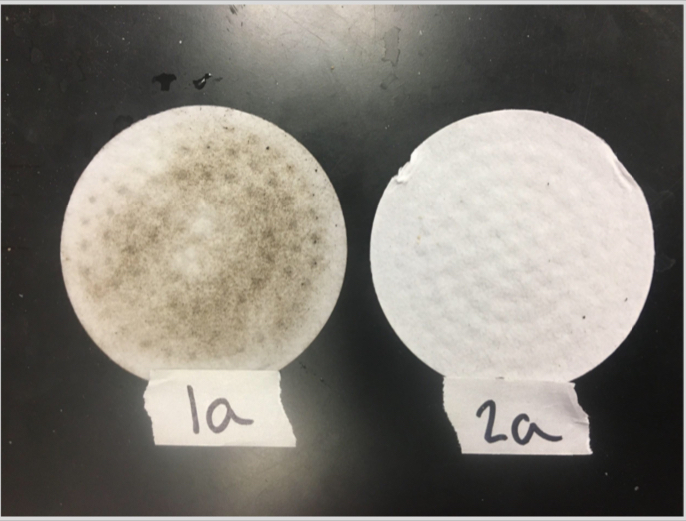

The last sample taken was a sediment sample that was used to measure the microplastic content. I found an average difference of 1.23 microplastics per gram between the upstream and downstream sites, with the upstream site having a lower microplastic content. The average difference between the two sites was found to be statistically significant.

When I came home after school with pictures of the plastics and my calculations, my mom was shocked. Here was concrete evidence that microplastics are not just some distant issue only affecting deep-sea fish. The threat of microplastics on the environment had officially reached Brevard, North Carolina.

Through this research, I discovered that the site just a few miles downstream had a significantly lower water quality according to the SMIE method. At first, I had assumed it had something to do with fertilizer runoff, but the chemical analysis found almost no difference between the two sites. This begged the question: What was happening that caused the water quality to decrease?

BMIs, which we were using to measure the water quality, live at the bottom of the river, in the sediment from which the microplastic samples were taken. Benthic macroinvertebrates also eat small bacteria and algae from the soil, which could lead to the consumption of microplastics.

If the BMIs are ingesting microplastics, that could cause a multitude of problems to the environment. Less BMIs means less food for larger aquatic organisms, which leads to problems for all the other animals further up the food chain. Additionally, most BMIs are actually the larval state of various insects, such as the mayfly and dragonfly.

If less and less of the larvae grow to maturity, fewer and fewer insects are available for birds and other wildlife, which leads to other problems in the ecosystem because of the unbalance.

Throughout this project, the thing that surprised me the most was that I found very little research being done concerning microplastics in freshwater ecosystems. Microplastics may be harming the ecosystem of Western North Carolina without anyone noticing.

Recently, MountainTrue has started integrating microplastic analysis into their sampling process. It was inevitable that microplastics would reach us here in rural North Carolina due to the world’s consumption of plastic products, but people must know and recognize that we are not immune to the consequences. Measures must be taken to monitor and possibly mitigate microplastic pollution everywhere, even here in western North Carolina.