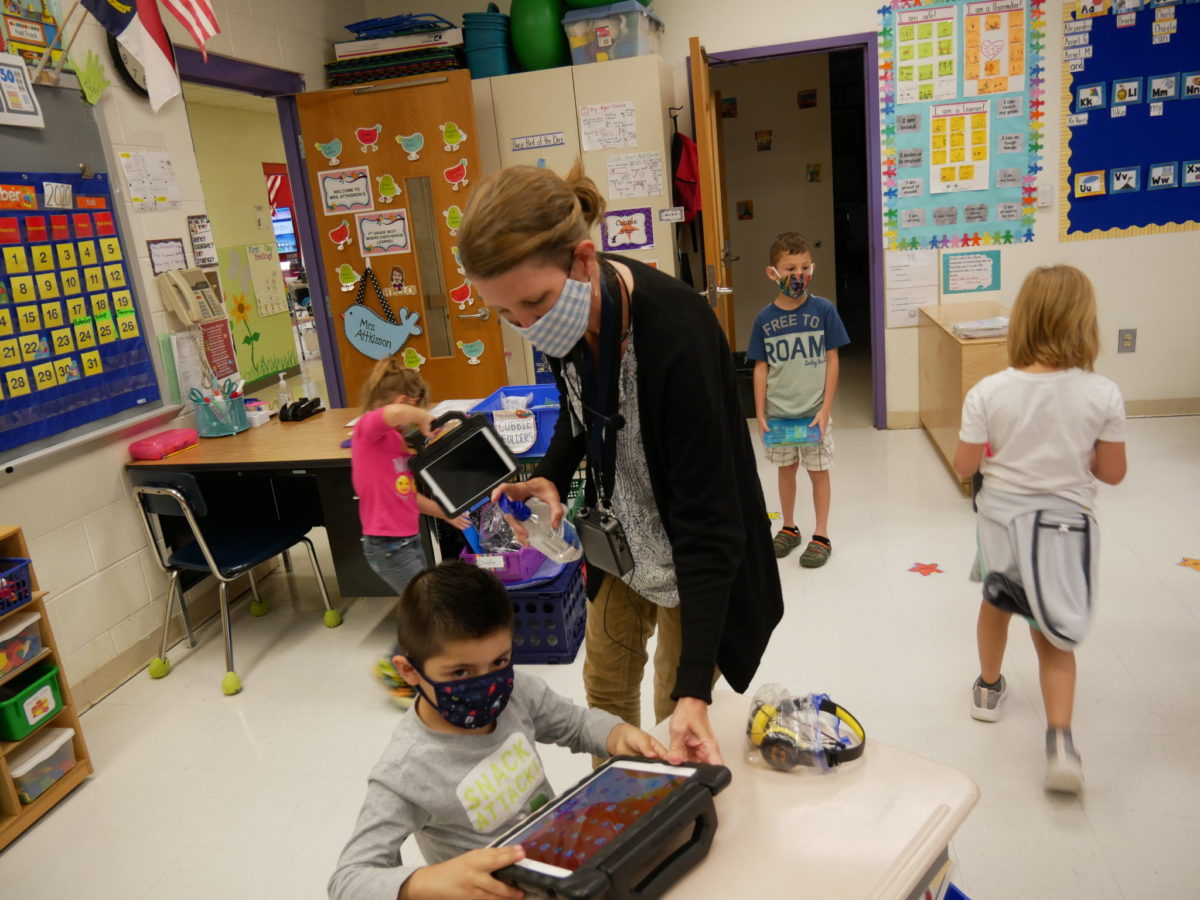

The neighborhood elementary school that sits at the half-way point of my morning walk awaits the return of its pre-K-3 students for in-person instruction on Oct. 26. Signs posted along the curving driveway to the entrance remind children, parents, and visitors: “Please stay at home if you’re sick.” “Be smart. Stay 6 feet apart.” “Wear a face covering and a smile!”

As North Carolina moves into the next phase of reopening public schools, the degree of success will hinge on a cascade of individual heart-tugging decisions by school administrators and staff, by parents and teachers. And those decisions come in a fraught atmosphere consisting of a viral pandemic, political polarization, economic distress, social media fact and fiction, community differences, peer pressures, and the homestretch of the 2020 elections.

And for both public officials and private citizens, these decisions demand at least some personal contemplation on ethics — that is, what should and should not be done in given circumstances. In her guest lectures to my UNC-Chapel Hill journalism classes, Social Work Professor Kim Strom, a scholar on moral courage and ethics, has taught students that “ethical dilemmas are not right vs. wrong, but rather, right vs. right.”

Educating children is right. Protecting them, their teachers, and their families from a powerful contagious virus is right. And yet, each right decision contains implications, a downside.

Prolonging virtual instruction threatens more learning loss, especially for at-risk students, and inconvenience to parents who need to work. And yet, too-quick reopening in the absence of a vaccine and of adequate school protective enhancements risks prolonging the pandemic.

In hindsight, it’s apparent that public schools are in a tough spot today because the nation did not lock down hard enough and long enough before springtime. By his own words on tape, President Donald Trump has disclosed that he knew the severity of the coronavirus in February and that he downplayed it subsequently to the public.

The president’s attitude and actions set in motion two dynamics. Rather than a common national response to the pandemic, leadership devolved to governors, mayors, and school boards to devise their own policies. What’s more, the response, symbolized by whether to wear a mask, became politicized, as state and local Republicans took their cues from the president of their party.

In North Carolina, Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper opted for an approach, guided by public health standards, of stay-at-home orders lifted step-by-step as virus trends warranted. His Republican opposition, including Lt. Gov. Dan Forest, has pushed for a speedier reopening of the economy and schools.

The upshot, as EdNC reported this week, is a state with an educational patchwork quilt — of classrooms as full as allowed, of a mixture of in-class and online, and of continuing virtual instruction until early 2021. The quilt reflects the uneven spread of COVID-19, differences in community size and attitudes, studies of the vulnerability of students at different ages, pressures from teachers who feel at risk, and personal ethical judgments.

North Carolina, thus, exemplifies a democratic society wrestling with hard decisions, struggling to find a balance between competing right and risk, facing the long-running tension between individualism and community.

As the nation was jolted last week by President Trump’s irascible debate performance and then his four-day hospitalization with COVID-19, Pope Francis issued an encyclical letter last weekend, not so widely noticed in the U.S. amid the political tumult. The pope, an Argentine, has an international audience and his message necessarily contains sections on Catholic-Christian theology. Still, Francis offered reflections relevant to the pandemic and politics in America.

Francis calls for a “better kind of politics, one truly at the service of the common good.” He chastises a “populism that exploits them (the vulnerable) demagogically for its own purposes, or a liberalism that serves the economic interests of the powerful.”

The coronavirus pandemic “unexpectedly erupted,” says the pope, as he was composing the letter of 287 numbered paragraphs. “God willing, after all this,”he writes, “we will think no longer in terms of ‘them’ and ‘those,’ but only ‘us.’ If only this may prove not to be just another tragedy of history from which we learned nothing. If only we might rediscover once for all that we need one another…”

Recommended reading