Much has been posted in the past few weeks regarding districts’s individual plans to move into plan B or plan C. Many districts and charter schools have selected plan B, while others have opted for plan C. Even prior to the governor’s announcement, districts carefully considered what their plans would like if we moved into plan A, B, or C, contemplating the nuances of what each plan option implicated for students, teachers, and families.

We also know that many districts across the state gave parents and caregivers an alternative plan to register for: virtual academies. These alternative plans were open for registration and most of them closed around the time that districts announced which plan they would move into.

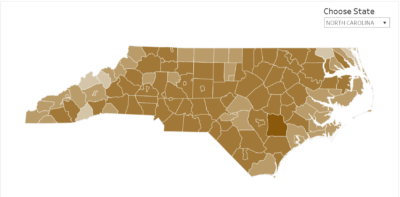

For districts that did not offer their own virtual learning experience, the state of North Carolina has three online learning platforms for parents and students to choose from: one is led under the helm of the state Department of Public Instruction, and the other two are charter schools. There is no final tally on how many students statewide have applied into any of these all-virtual learning platforms; and districts are seeing a wide range, with some as low as approximately 4% to others as large as 41%.

Even without final numbers, what is still clear is that there will be a lot — and I mean a lot — of students online in some capacity for the foreseeable future. This week, many districts and charters began their remote learning plans.

On the offset, it should be noted that districts are working under some of the tightest deadlines they have had to work with. It is not just considering, “How do we make learning happen online?” For many, if not most districts, there are just as many deep issues to consider:

- How will the kids be fed?

- Does every child have access to WiFi? If not, how do we help them?

- Does every child have a reliable technology device to do their work on? If not, how do we help them?

- How can we appropriately serve our exceptional children, and help meet the qualifications of their 504s and IEPs?

- What do we do for the children whose parents cannot stay home with them?

This article will not exist to attempt and answer these questions. This list is only a tip of the tip of the iceberg that districts were frantically looking to answer before the legislated start date of August 17. While I have my own opinions on how a lot of this has shaken down, what is necessary to discuss is an underlying question that has not been given enough face time — if you’ll allow the pun: How much screen time is “just enough” screen time?

A look at the research

To be fair, a large portion of research that has been conducted over the years in relation to children/adolescents and media use has been specific to television viewing experiences, video gaming, and screen time with children ages 0-5. Much of what COVID-19 has pressured school systems into is utilizing screen time as an effective resource for teaching, combined with utilizing teaching tools to enhance the learning experience. Zoom, Google Meets, and other video conferencing platforms have been implemented like never before, particularly in the K-12 space.

While “real time studies” are still being conducted on the effects of remote learning during COVID-19, there are still some key takeaways we must consider.

1. Video conferencing and remote learning do not replace face-to-face (F2F) teaching.

I will not expound upon this particular aspect, as there are better writers who have captured this thought and moment well in their own writings. Just know that among the many reasons why remote learning does not replace F2F teaching, establishing and building critical relationships — which simultaneously depends on social skills and body language — is crucial to excellent teaching.

2. Not every family can have flexibility. Not every family can have structure.

This is the two-sided coin that every district in plan C is facing at the moment. Many parents have established that they want or need their child to have a structured and timed “school day” because they are also working from home. They need their children to be engaged in something that is productive, so that they can also be productive.

On the other side of this coin are the parents who are not in a position to provide the same rigid structure at home on a daily basis. For some working parents, they may be nurses or doctors with schedules that do not declare themselves until a moment’s notice. For others, it may be that they are hourly workers whose schedule is made at the mercy of an employer, who may be currently understaffed. In these scenarios, the more flexible the structure, the better for their family.

3. Zoom fatigue is real for adults, which also means it is real for students.

Much has been written in the past few months on the concept of “Zoom fatigue” for adults. It seems that little has focused on the significant impact that this same fatigue is having on K-12 students. It is a safe assumption to state that if Zoom fatigue is an accurate experience for adults, then it is definitely an accurate experience for students. The greater likelihood is that this Zoom fatigue can drain students quicker than it does with adults. Again, this is a field that has limited studies, as more studies focus on gaming or virtual reality, rather than remote learning. But some studies have shown the impacts of social cues (both a lack and over abundance of) with a remote setting, and the impacts on student cognition.

4. Tech equity: Not everyone is working on the same playing field; or even in the same park.

From computers freezing and lagging to considering that others can see your own home (which some students host a sincere anxiety over), online learning is increasing many anxieties for everyone in an already-anxious world. For one, access to reliable and high-speed internet is not equitable across the state. How many of us have been in a Zoom meeting where we discovered turning our videos off increased the bandwidth, and functionality worked better?

Beyond the hardware and application concerns of equity, some students are conscientious about their home-life and how they are perceived by peers. Creating mandates, such as requiring that students must have cameras turned on to count as present, or that lunch is completed with video on as a group, only increases the level of anxiety these students feel. And let’s not forget that some students may not have access to lunch when they “join” the group.

Considerations for districts

At this point, districts have solidified their plans for the upcoming quarter with how they intend to engage in remote learning. However, this does not mean that those plans must be etched in stone. While not always the easiest choice, the one major benefit to remote learning is that schools and districts can pivot more quickly to address significant concerns and potentially unintended consequences.

For these remote districts, I would offer these considerations as we move into the new school year.

1. Have frequent check-ins with all school members.

It is safe to assume that the start of the unknown will be met both with trepidation and with a semblance of excitement. However, those feelings can wear off quickly and eventually a sense of the “norm” will begin to shape. When that norm sets in, many individuals (students, teachers, and parents) will want and need an outlet to express what is happening. A check-in of some type should be a part of the new norm, and it should be completed with frequency.

The check-in should not be implemented solely as a box to check off for the district. Rather, it should be both meaningful and intentional. Meaningful in the questions that are asked, with an option to expand responses. Intentional in that there is a true desire by the district that says: “pending these remarks, we may seek to pivot.” Your community may come back and tell you overwhelmingly what a fine job you all are doing as a whole to address this online learning; but the opposite may also be true, and shifting gears may be required.

2. Set realistic time-spans for students.

It should be noted that many districts, as of late, are recognizing that the amount of screen time a kindergartner can withstand is significantly different than what a 12th grader can. With that said, there seems to be a growing understanding that in order for remote learning to happen, students and teachers must be logged in 100% of the time during normal business hours. That is not remote learning; that is more or less online babysitting. Remote learning in a true sense allows students to work at their own pace and on their time.

Typically, in a virtual classroom setting, there is a “spacing out” of Zoom meets and times: a teacher will have designated face-to-face hours where students can freely drop in and ask questions; or the teacher may request a specific student or group of students to meet and work specifically with them to deepen understanding.

This concept of spacing out allows for the brain to decompress from the over-stimulation provided by both visual and aural settings required of Zoom. Remote learning of this nature allows for both educators and families to implement more explicitly the American Academy of Pediatrics general recommendation of a two-hour average screen time use for older age groups, while still modifying times for younger ages.

3. Set realistic expectations for families.

Even I as an adult feel exhausted just by thinking about the amount of video conferencing that is expected, both as a teacher and as a student. And while I have no doubt that the excellent pool of teachers we have across the state will do everything within their own powers to create authentic learning environments for their students, 5+ hours of video conferencing every day will not provide you with quality and authentic learning.

Even without the “Zoom fatigue,” however, the second item in the section above really paints the most vivid picture of why the more rigid structures and expansive screen time hours are not so healthy. For the parents that need their children to be engaged so that they may get their work done, that may be well and true. But, what if that child is a first-grader and is learning the ins and outs of technology for the first time? How productive does the parent feel is this scenario?

Even for those who engage with remote learning in the spring, the fall has a different aura around it this go-around. For one, students will not be offered a pass/fail option, so more hangs in the balance of work completion and performance. But still, there are many families who are dealing with new issues than what may have been present last spring. A significant consideration is the number of adults who have become unemployed as a result of COVID-19. More families will depend on the opportunity to have flexibility in their schedules — flexibility for students to “attend” school and to turn in their work.

It has been stated time and again, but we are certainly living in unprecedented times when it comes to education. Educators across the board from the bus drivers to the superintendents are being asked to rethink education, some of us in more dynamic ways than we have ever had to. Being successful this fall, and ultimately priming our students for a successful re-entry into a face-to-face mode of learning, will require succinct, explicit, and intentional thought on what is healthiest for our students and communities.