|

|

While much Black history coverage featured in K-12 curriculum focuses on national moments and figures, North Carolinians also have rich Black history in our own backyard — especially connected to the struggle for civil rights. For students, that proximity can be powerful. So today, let’s lift up a few places, people, and moments in North Carolina civil rights history to remind young people and adults alike that the next generation of North Carolina’s leaders and change-makers are likewise right here in our own communities.

As is my personal bias, let’s start in Durham. In the 1910s and 20s, Pauli Murray grew up in the Bull City, attending Hillside High School and St. Titus Episcopal Church. Murray would become a prolific and trailblazing community organizer, lawyer, reverend, and author, pioneering an “intersectional” approach to racial, class, and gender equity work long before that word ever existed. Murray’s prodigious life and career paved the way for countless other lawyers and organizers who drew upon Murray’s work, including future Supreme Court Justices Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

An hour or so west, Greensboro made its mark in the movement, too. On February 1, 1960, for instance, four North Carolina A&T freshmen — Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, and Jibreel Khazan — staged a historic sit-in at the segregated lunch counter at the Woolworth’s store in Greensboro. The “Greensboro Four” were far from trained organizers — they had just graduated from high school — but felt an overwhelming conviction to do something to act against injustice. The spark of their simple, courageous act was lifted by the winds of history and ignited similar activism for racial justice across the South and the nation.

Just a few months later, that spark landed in Raleigh. In April 1960, Littleton native and civil rights organizer Ella Baker convened a conference of student leaders at Shaw University (where she had graduated as valedictorian) to transform this pivotal moment into a sustained movement. The organization that emerged from this gathering — the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) — would become among the most impactful groups in the Movement, forging young, dynamic, national leaders such as John Lewis, Diane Nash, Julian Bond, Stokely Carmichael, and Bob Moses. In the years to come, what started in Raleigh would transform the nation.

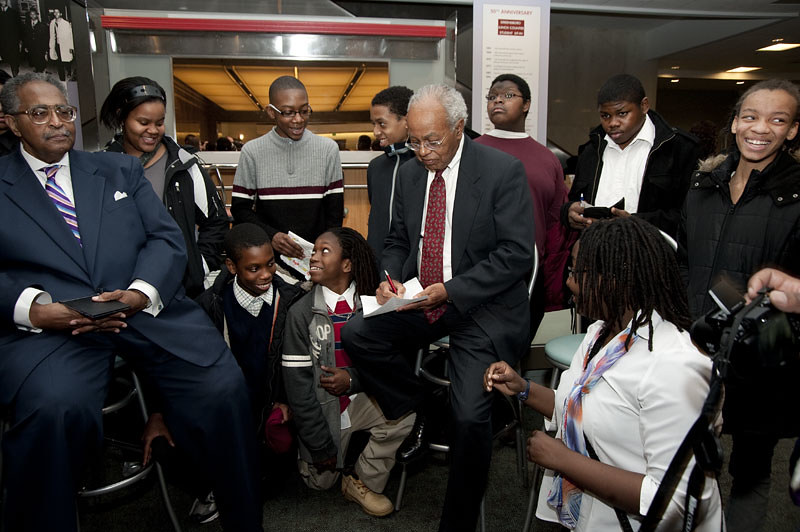

And don’t forget Charlotte. Of the many notable moments and people in Queen City civil rights history, Julius Chambers is among the most significant. A Mount Gilead native, Chambers attended N.C. Central (where he was student body president) and UNC Law School (where he was valedictorian and the first Black editor-in-chief of the law review) before becoming among the most influential civil rights lawyers in American history. His work from small North Carolina courthouses up to the U.S. Supreme Court advanced racial equity in education, voting rights, and employment, and inspired generations of North Carolina civil rights advocates to come.

Rural North Carolina communities have made civil rights history, too. In 1982, for instance, community members in Warren County organized prolonged protests against the state’s dumping of toxic soil into the county’s landfill. By drawing national attention to the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on marginalized communities of color, Warren County inspired a new focus within the Movement: environmental justice. Today, rural, predominantly Black communities across North Carolina continue to advance Warren County’s legacy by leading the movement for safe air, water, and soil for all.

Of course, this short list is incomplete. But it already begins to teach us a foundational lesson of Black history and American history: Ordinary people showing extraordinary courage can spark systemic change. And often, it’s young people who lead the way. So today, let’s remember that North Carolina’s next generation of history-making entrepreneurs, writers, lawyers, and community leaders are currently sitting in classrooms across our state. When we invest in those students and classrooms, we plant the seeds for a better, brighter, more equitable North Carolina for us all.