When I learned that former Ambassador James A. Joseph died on Feb. 17, my mind turned to the provocative question he often posed as a lesson arising from the biblical parable of the Good Samaritan. It is a lesson to guide lawmakers amid the divisive politics and cultural clashes burdening our state and nation.

Chapter 10 of Luke’s gospel tells of a man beaten along the Jerusalem-Jericho road. A Levite and a priest pass him by. Then an outcast Samaritan acts as a genuine neighbor by bandaging his wounds and taking him to an inn to recuperate.

While recognizing the value of person-to-person compassion, Joseph asked, “Who has responsibility for policing the road?”

And he didn’t intend to limit the focus to law enforcement. He surely meant his question to extend to who has responsibility to fight ignorance, to combat the despoiling of air and water, to reduce hunger and homelessness, and to prevent and treat disease.

“What started out as an individual act of charitable aid leads to a concern with public policy,” Joseph said.

I got to know Joseph during the 2000-2011 period when he was leader-in-residence in the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. He also served as chair of the board of MDC Inc., the Durham-based nonprofit research organization, for which as a senior fellow I worked on State of the South reports.

Joseph, who died a month short of his 88th birthday, grew up in Opelousas, Louisiana. He said he had “fond memories” of the Cajun and Creole cultures, but also recalled having to walk past an all-white school to attend “the so-called colored school” where the students studied “from hand-me-down books in a hand-me-down building.”

He graduated from Southern University, an HBCU in Baton Rouge, and subsequently earned a divinity degree from Yale University. He was an ordained minister. His career was long and multifaceted: a university chaplain, an officer in the Army medical corps, founder of a civil rights organization, vice president of Cummins Engine Company, and president of the national Council on Foundations.

His experience in organized philanthropy led to his appointments to the board of President George H.W. Bush’s Points of Light Foundation and to the Louisiana Disaster Recovery Foundation formed after Hurricane Katrina. What’s more, he wrote four books.

From 1996 to 1999, Joseph served as U.S. ambassador to South Africa, appointed by President Bill Clinton. In that role, Joseph dealt regularly with President Nelson Mandela, who was engaged in the delicate task of solidifying a post-apartheid government.

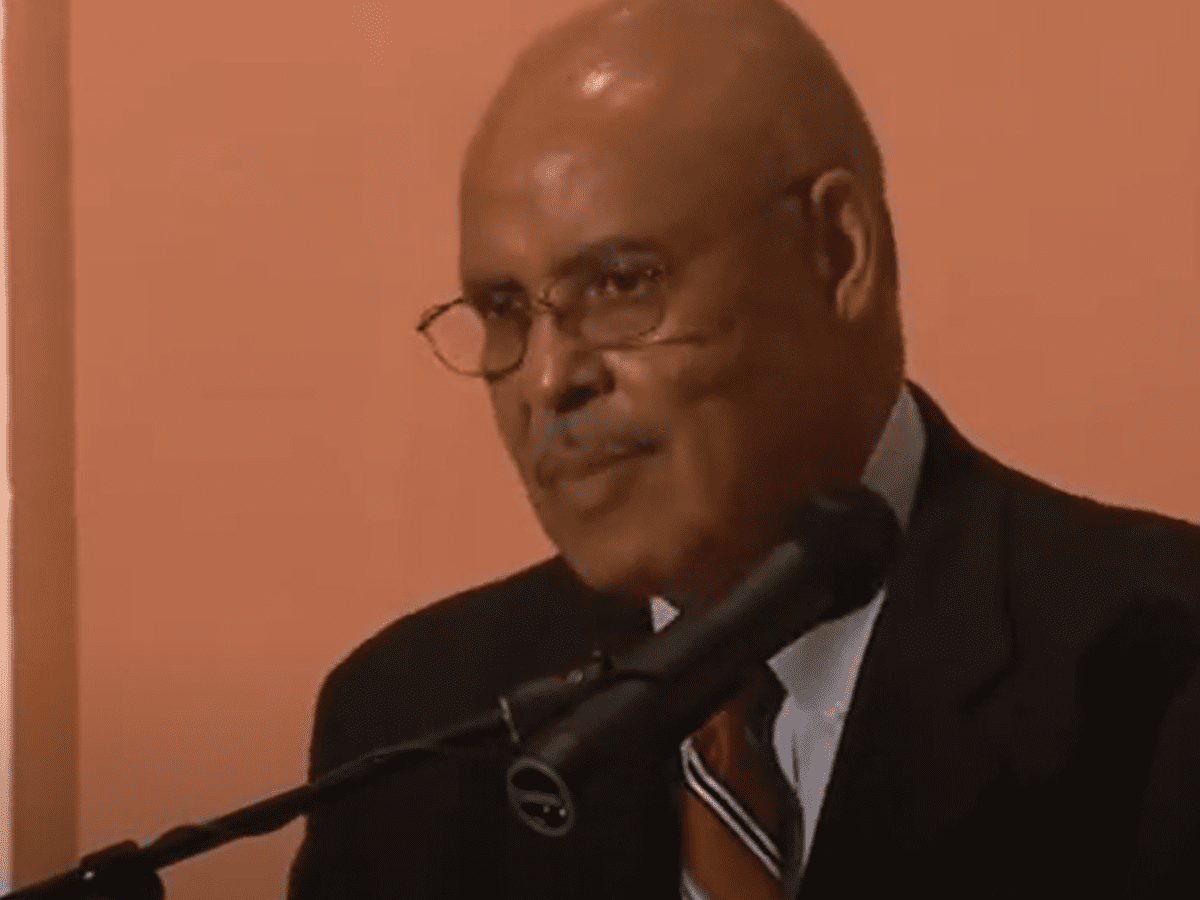

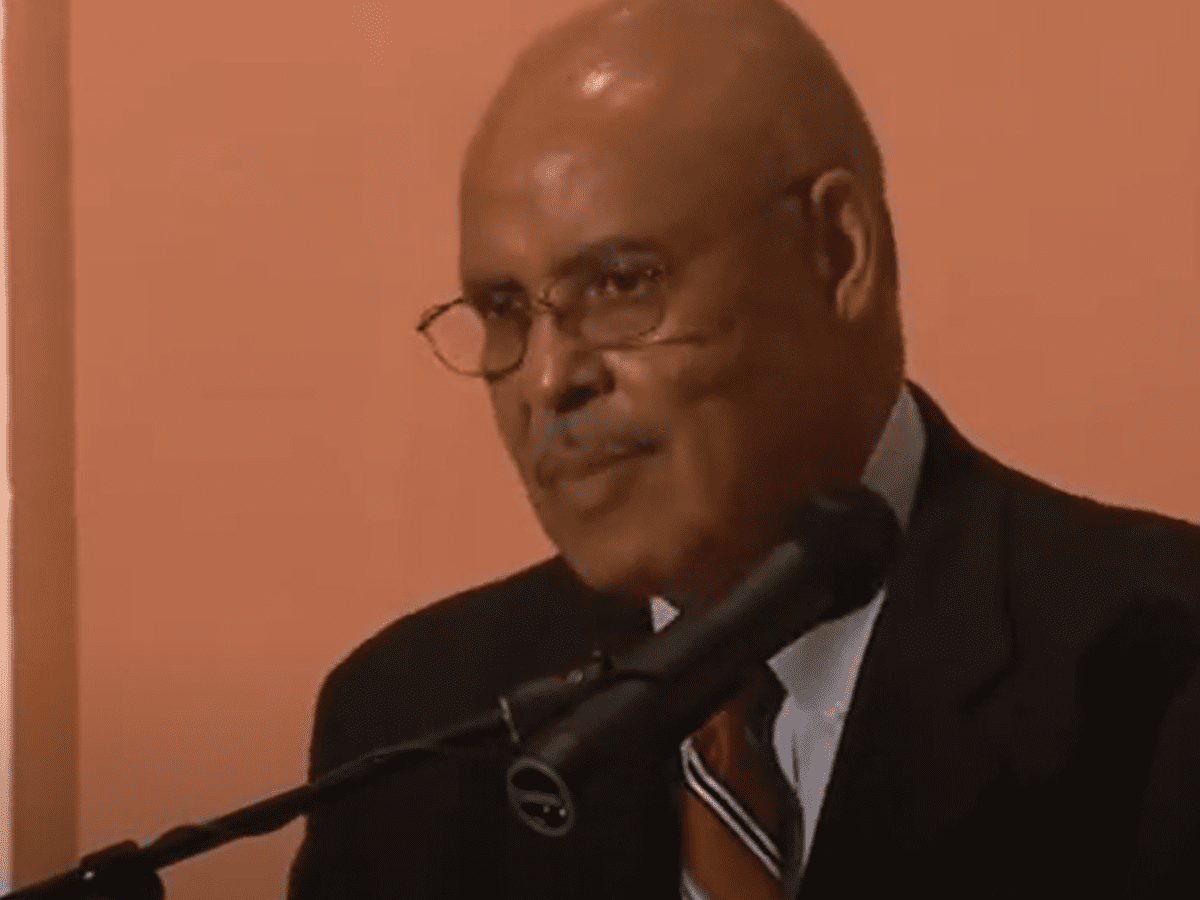

In September 2009, Joseph delivered the Lambeth Lecture at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I re-read it and watched the video below. In it, he posed the Good Samaritan question as part of an extended meditation on philanthropy, higher education, and civic engagement.

“The moral imperative of civic engagement is to help transform the laissez-faire notion of ‘live and let live,’ into the principle of ‘live and help live.’” he said.

His lecture came amid an economic downturn so severe that it is known as the Great Recession; the federal government appropriated billions to prevent a collapse of banking and automobile manufacturing. It came before the emergence of the Tea Party faction and the hardening of partisan lines. When Joseph spoke, he could not have known that a COVID outbreak would shut down schools, or that a mob would assault the nation’s Capitol, or that more than 100 elected representatives would vote to block certification of a presidential election. He spoke before the reemergence of “culture war” on matters of race and gender affecting schools in North Carolina and elsewhere.

Still, nearly 14 years ago, Joseph detected a “unique moment of free-floating anxiety.” He worried that “what should be its finest hour, the idea of civil society is in danger of being distorted and hijacked by those who emphasize its potential in order to bolster arguments for a more limited social role by government. Some of the strongest advocates of civic engagement are people with an uncivil state of mind.”

And he posed another challenging question: “How do we build community?”

“It has been my experience that when neighbors help neighbors, and even when strangers help strangers, both those who help and those who are helped are not only transformed, but they experience a new sense of connectedness,” he said. “… When that which was ‘their’ problem becomes ‘our’ problem, the transaction transforms a mere association into a relationship that has the potential for new communities of meaning and belonging.”

Joseph brought together intellectual prowess and wide-ranging personal experiences to have the confidence to address with nuance and rigor his own provocative question drawn from the Good Samaritan parable.