|

|

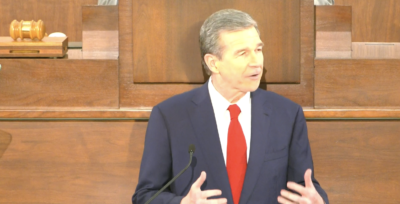

Surely Apple Inc. and the U.S. Census Bureau didn’t coordinate their big-news announcements on Monday, April 26. Still, Apple and the Census converged to confirm Gov. Roy Cooper’s assertion in his State of the State address in the evening that North Carolina has emerged “strong” after a year of “suffering and loss.”

As a key part of a five-year expansion, Apple announced that it would build a new campus on a Wake County site within Research Triangle Park. The computer company said it planned to invest more than $1 billion in North Carolina and projected “at least 3,000 new jobs in machine learning, artificial intelligence, software engineering, and other cutting-edge fields.”

For its part, the Census Bureau released the initial broad state-level results of the 2020 census, which counted 10.4 million people in North Carolina. Population growth of slightly more than 900,000 since 2010 was enough to qualify the state to jump from 13 to 14 U.S. House seats.

A new RTP occupant, however huge, and an additional congressional seat are not so much game-changers, economically and politically, as they are signifiers of North Carolina’s dramatic changes over the past three decades. Public K-12 schools, community colleges, and universities have helped shape societal changes, and now face challenges in responding to changes still playing out.

From 1990 to 2000, North Carolina grew from 6.7 million people to slightly more than 8 million, and then grew to 9.5 million from 2000 to 2010. While still robust, North Carolina’s rate of growth — 9.5% — since 2010 was well below the double-digit rates in the previous two fast-growth decades.

As North Carolina emerged as a mega-state, its growth in people and jobs increasingly concentrated in its major metropolitan regions of core city, suburbs, exurbs, and connected towns. The Triangle and the Charlotte metropolitan region are the state’s two powerful magnetic poles of the state’s economy.

In March, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported, North Carolina had 4.46 million jobs — 1.2 million in the Charlotte metro (which includes a slice of suburbs in South Carolina), 638,000 in the Raleigh metro, and 320,000 in the Durham-Chapel Hill metro. Thus, the Triangle and Charlotte regions account for nearly half of North Carolina jobs.

Growth and prosperity have not spread evenly across North Carolina. Meanwhile, Carolina Demography has reported that “population estimates suggest that 43 of the state’s 100 counties may have lost population over the decade.” For people, similarly, the state is experiencing a K-shaped uneven recovery in both the economy and education from a pandemic that exposed embedded inequalities.

Implicitly recognizing differences in capacity and need among North Carolina communities, Apple pledged to “establish a $100 million fund to support schools and community initiatives in the greater Raleigh-Durham area and across the state.” Without going into details, Apple also said it “will be contributing over $110 million in infrastructure spending to the 80 North Carolina counties with the greatest need — funds that will go toward broadband, roads and bridges, and public schools.”

Before Apple, the state’s largest economic-development deal came in the summer of 2020, when Centene, the huge managed-care and health insurance company, announced it would establish a regional headquarters and technology hub in the University Research Park in Charlotte. It’s instructive to read what Centene CEO Michael Neidorff had to say at that time, as reported by the Carolina Ledger Business Newsletter: Charlotte, he said, “has all the elements of a great city: successful schools, impressive infrastructure, great diversity and tremendous opportunity for upward economic mobility.”

Despite their economic prowess, Charlotte and Raleigh were found in a 2014 study to offer weak upward propulsion to children who grow up in low-income families — a persistent challenge for their civic leaders to address. Big companies such as Apple and Centene can contribute to the state’s future not only in high-paying jobs and in good corporate citizenship, but also in helping North Carolinians understand more deeply how their schools, colleges, and universities form an infrastructure of opportunity and upward mobility.