David S. Tatel has decided to retire as a full-time judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. A recent story on Tatel in The Washington Post focused on his influential judicial career but did not mention, as I remember, his central role in a major higher education desegregation case that resulted in strengthening North Carolina’s five historically Black public universities.

During the 1977-78 period when I was Washington correspondent for The News & Observer, Tatel served as director of the Office of Civil Rights in what was then the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Retinal disease left him blind, but did not deprive him of insight and initiative. He struck me as a diligent, thoughtful public official, even if reticent to disclose details during difficult negotiations with President William Friday and his chief aides in the University of North Carolina system.

“In nearly three decades on the appeals court in Washington,” the Post wrote, “Tatel’s lack of eyesight has never defined him. But his blindness — and more recently the attentive German shepherd at his side — is now woven into the culture of the courthouse where Tatel has been at the epicenter of consequential cases affecting major aspects of American life.”

The Post story simply said Tatel “revived” the HEW civil rights division. There, he became enmeshed in the Adams case that ordered federal officials to apply the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to public colleges and universities in 10 states — both to bring more Black students and faculty onto predominantly white campuses and to preserve the distinctive role of historically Black institutions.

UNC officialdom argued emphatically that proposed remedies, such as moving curriculum programs to eliminate duplication, would impinge on public universities’ autonomy in academic decision-making. Meanwhile, Black leaders fretted over talk of mergers and over the potential of white institutions creaming away their top student prospects.

In his 1995 book, William Friday: Power, Purpose and American Higher Education, historian William A. Link devoted more than 100 pages to the negotiations that stretched from Richard Nixon’s presidency, through Jimmy Carter’s, and into Ronald Reagan’s. Link described the desegregation issue as the “supreme test of Friday’s university presidency.” And, he wrote, Tatel, a Carter appointee, viewed North Carolina as the “most important” state in the case because of Friday’s stature and because North Carolina “possessed the best public university system in the South.”

In February 1979, Tatel and Assistant Secretary of Education Mary Frances Berry led a team of federal officials on a three-day visit to eight North Carolina public universities, including the five historically Black campuses. Here is how Link summarized their findings:

“Tatel described the ‘reality of it’ as ‘overwhelming.’ At (NC) Central they toured a physical education building with dank classrooms and a leaky roof; the swimming pool in the gymnasium was considered too unclean to swim in. At Fayetteville, one faculty member told Tatel that if he wanted his students to conduct serious science experiments, he sent them to local high schools where the equipment was superior.”

The tour sent a bolt of lightning into the negotiations by illuminating North Carolina’s Black universities. Though the case dragged on beyond Tatel’s term and into the Reagan years, Link reported, the General Assembly appropriated more than $95 million in construction and renovation for Black universities through the 1980s, as well as brought their state funding up to the level of comparable white universities.

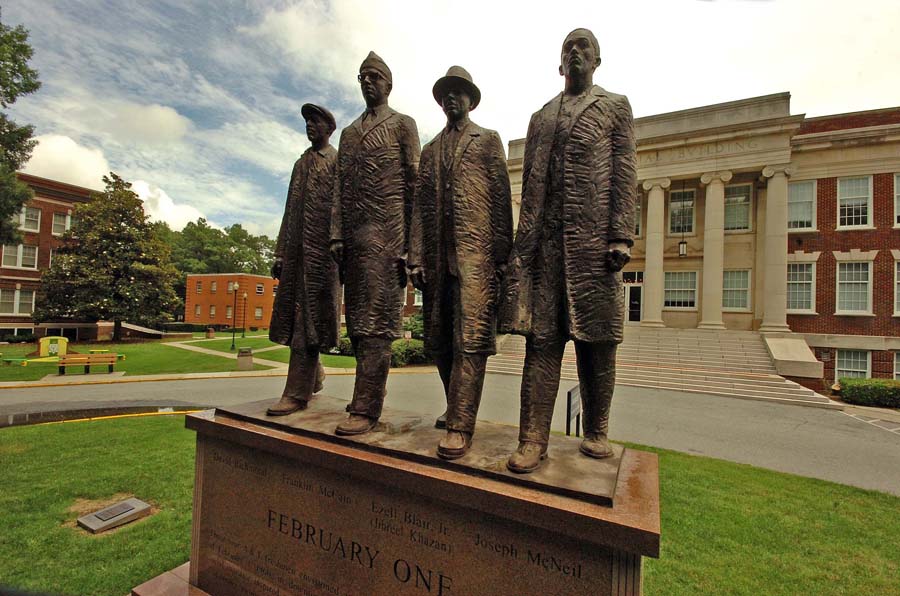

Fast forward three decades. North Carolina remains the state with the most public historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU). Of the 242,000 students enrolled in the UNC system in the fall 2020 semester, 34,728 were in the five historically Black universities. With more than 12,000 students, North Carolina A&T State University is the nation’s largest HBCU — and it ranks among the top four UNC institutions in research funding.

Earlier this week, The New York Times proclaimed that “historically Black colleges and universities are having a moment.” North Carolina’s institutions are sharing in the moment.

“And money is pouring in,” The Times reported. “The philanthropist MacKenzie Scott has given more than $500 million to more than 20 historically Black colleges in the past year. Google, TikTok and Reed Hastings, the co-chief executive of Netflix, have given $180 million more. Lawmakers on Capitol Hill delivered more than $5 billion in pandemic rescue funding, which included erasing $1.6 billion in debt for 45 institutions.”

Scott, the former wife of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, has given $45 million to NC A&T, $30 million to Winston-Salem State, and $15 million to Elizabeth City State. NC Central has broken ground on a new business school, while the NC Teaching Fellows Commission has selected Fayetteville State and NC A&T (as well as minority-serving UNC Pembroke) for expansion of the Teaching Fellows Program.

In April 2021, the Board of Governors voted to allow the five public HBCUs to raise the cap on out-of-state first-year students to 25%, a move that responds to demand from non-residents and that would bring in more tuition revenue. Elizabeth City State, which has the state’s only four-year aviation science program, is one of three NC Promise universities with $500-per-semester tuition for North Carolinians.

Historically Black universities, of course, confront challenges arising from demographic shifts and state fiscal austerity as does public higher education generally. Still, that tour Tatel led four decades ago into North Carolina gave HBCUs a chance to survive and advance to their current spotlight moment.