|

|

Nobody thought it would be Elizabeth City, this river city of 18,000 just north of the Albemarle Sound.

The racial dynamics have long been tricky in the mostly Black city, the seat of government for mostly white Pasquotank County. But local government leaders, community advocates, and university leaders had endeavored many times to prevent something like the police killing of Andrew Brown Jr.

They formed a group in 1992 to promote racial unity. About 11 years ago, they held a community dialogue around race. Recently, after the murder of George Floyd by a Minnesota police officer, the community held a two-day workshop called “Building Bridges to a Better Understanding” that brought together 40 leaders from the area.

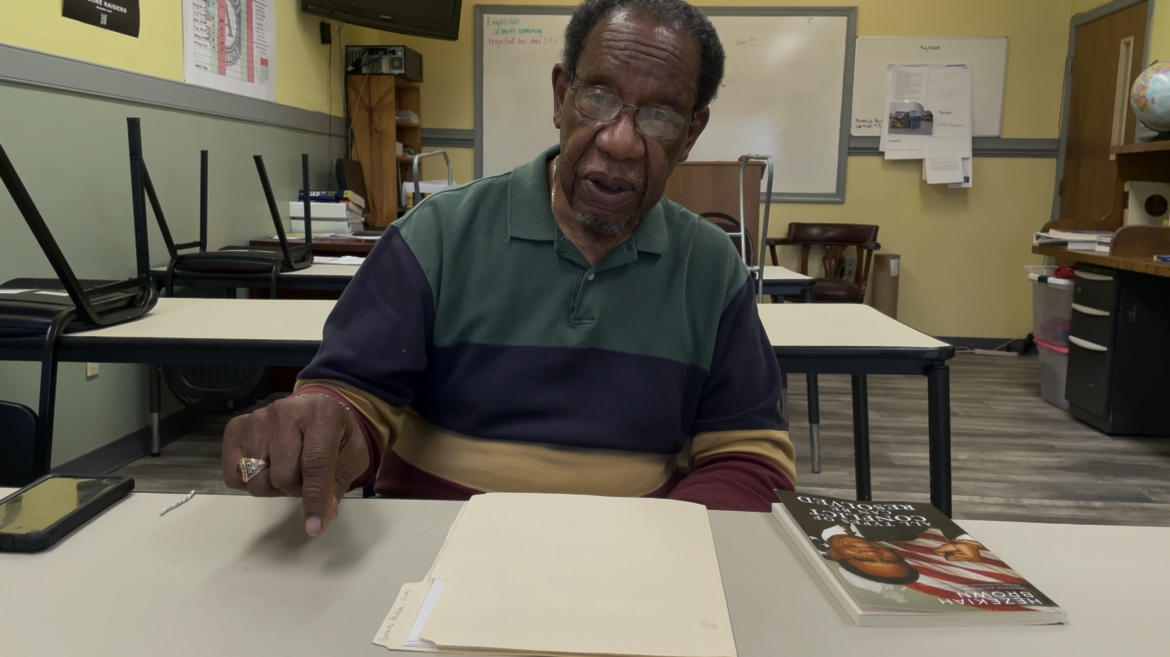

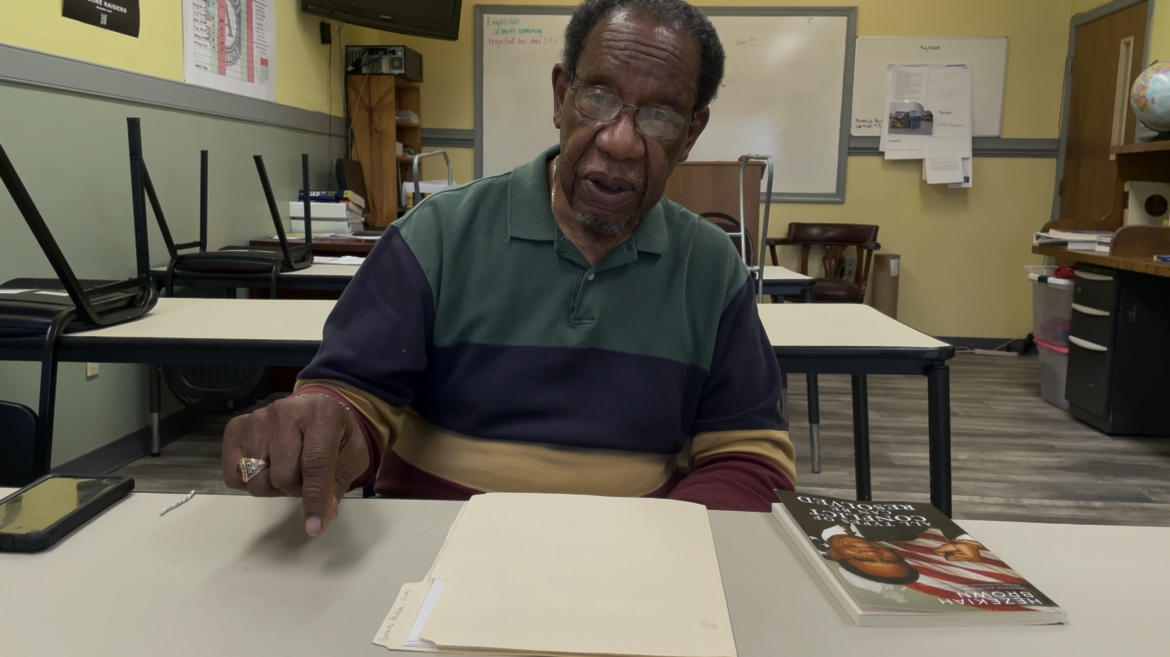

“To be honest, we did it to prevent the same thing from happening here,” community leader Hezekiah “Hez” Brown said.

Yet, it happened.

Hez Brown is a former federal mediator and was co-facilitator of the Building Bridges program. He said the events taking place in the city after police shot Andrew Brown Jr. on April 21, and during the delay in releasing officer body camera footage, reflect the power of systemic forces. It’s evidence that unity among individuals is important, he says, and yet those relationships operate separately from divisive policies and disparate outcomes at a systemic level.

“This has proven now that we need each other,” said Hez Brown, who was the chair of the former Board of Visitors for Elizabeth City State University. “There’s no silos here. And it’s going to take all of us here working together to destroy systemic racism.”

Peaceful protests bring multiracial, multigenerational crowds

For 12 nights, protesters have gathered to walk the streets and to sit in front of the county sheriff’s offices. They’ve marched past the house where Andrew Brown Jr. lived and was killed, stopping for moments of silence and prayer.

The protesters shout and sing, they play music and dance — they make their presence known. Yet, there are no bricks going through windows or violence in the street. Not a single business or home has reported damage from the protests.

“When they say peaceful protest, this is what it looks like,” said Jimmy Chambers, a junior at ECSU who is serving his second term as president of the student government association. “They understand that this is where we live, this is our community. So they’re not going to vandalize it.”

Unable to anticipate what would happen after Brown was killed, county and city officials made a number of decisions — many of which have come under the scrutiny of those they were meant to serve.

Brown was killed on a Wednesday, and there were peaceful protests that night. On the following Sunday night, April 25, the academic institutions in the county met to discuss requests from Elizabeth City officials and law enforcement.

Representatives included leaders from the two universities, ECSU and Mid-Atlantic Christian University; the local community college, College of the Albemarle; the charter school, Northeast Academy for Aerospace and Advanced Technologies; and the Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Public Schools.

One of the requests was to help keep roads clear, so all of the academic institutions agreed to go all-remote starting Monday, April 26. ECSU also made the decision that night to send students off campus, with the goal of sending students home by Tuesday.

On Monday, Elizabeth City Mayor Bettie Parker, a 1971 graduate of ECSU, declared a state of emergency. University officials said that on Tuesday morning they received a request from the city to host out-of-state law enforcement brought in after the emergency declaration. That morning the city instituted an 8 p.m. curfew.

The outcry was swift on social media, from K-12 parents upset with having to return to remote schooling, university students outraged at having to vacate their campus dorms only to learn out-of-state law enforcement would be staying on campus, and a number of protesters frustrated by the 8 p.m. curfew.

“I feel like some of the precautions that the city made were really unnecessary, you know, putting a curfew on something that is so peaceful and calling a state of emergency where now you’ve got outside agencies coming in,” Chambers said. “Now you’ve got officers who don’t really know these individuals, and that’s just going to cause more tension.”

The tension created with protesters coming face-to-face with law enforcement after curfew the past week stood in stark contrast to the tenor of most of the demonstrations. The protests have largely brought people together — people of all ages and races. Maenecia Cole is an academic advisor at ECSU. She watched the protesters walk down her street as she smiled and waved at people she knew.

“This is not the first,” Cole said, speaking of protests in the community. “This is just the first that the community has come together — Black, white, and all diverse nations. It used to just be the Blacks, because this was a segregated town. So this is just awesome. I love it because we’re not just looking at us, at people of color, out here.”

On a Friday night, Karissa Cooper sat with two friends on a curb in the parking lot between the county’s public library and sheriff’s office. The junior at Northeastern High School outlined block letters that she would later fill in to read, “Black Lives Matter.”

She needed to join the protesters, she said, to show support for the family and find a space to voice her feelings.

“They stopped the students from going to school because of the situation, so we’re online,” Cooper said. “And the teachers, to be honest, are very vague about talking about this situation. For schools, sometimes they don’t want to get into controversial talk, so they didn’t really talk much about it.”

A community that wanted to prevent this

For decades, Elizabeth City watched other locales as they dealt with racial unrest — and local leaders determined that they would prevent similar divisions from creating it in Elizabeth City.

That’s why two men, one Black and one white, shook hands in 1992 to create the Hope Group. Cader Harris, a white businessman, and W.C. Witherspoon, a Black educator, watched the L.A. riots in the wake of the acquittal of officers who beat Rodney King. They formed the Elizabeth City Hope Group to engender racial unity in the city.

Following up on the Hope Group’s work, the Elizabeth City City Council and the Pasquotank Board of Commissioners agreed to form the Community Relations Commission about a decade later, “to promote the equal treatment of all individuals, discourage discrimination of all types and to promote harmony and equal opportunity among all people.”

Two men heavily involved in Elizabeth City’s race relations watched demonstrators in Elizabeth City after the killing of George Floyd. Hez Brown, a Black man who has lived in the city for nearly 20 years, and Kurt Hunsberger, a white man who has lived there for 45 years, led the two-day convening at the community college.

“It was almost like a miracle that we were able to get the players to the table to talk about systemic racism,” said Brown, who served on the Community Relations Commission for nine years and is a co-chair of the Hope Group. “We acknowledged that systemic racism was an issue, not just in this city but throughout the country.”

In the 10 months since that convening, Brown said some solutions were starting to take hold. But they wouldn’t have stopped what happened on April 21.

Many of the initiatives look like engaging Black and white residents in events and outings to promote community, or the establishment of a unity team that brought local leaders together with students from the community college and two universities. It also included Pasquotank County Sheriff Tommy Wooten II.

“As a matter of fact, before this happened, I had talked to the universities and the college about bringing the same group of people back together, and we had agreed that it was going to be done — we were in the planning process of doing that,” Brown said. “But that wouldn’t have stopped what happened.”

Brown said that the various community groups have laid a solid groundwork and he feels optimistic about future race relations in the city. But many of these initiatives are directed at individuals, Chambers said, while he and others also want to see a different kind of change.

“Right after the verdict came out of George Floyd’s murder, we kind of took a sigh of relief,” he said. “Like the justice system is finally understanding us and seeing what we see. And then — boom — we have Daunte Wright happen and now we have, here in Elizabeth City with Andrew Brown Jr. It’s like we took four steps back after we just took that one great step.”

That’s why, he says, student voices are loudly crying out for systemic change — to state, county, and even university policies.

An engaged student body, schooled in activism

At a time when residents are protesting policing, students are directing their activism at their university. When ECSU sent students home, many had to leave the city. It was an opportunity missed, Chambers thought, for students to participate in the demonstrations.

“I do wish that our students could see this, this side of Elizabeth City where we can do civic engagement,” Chambers said. “I wish they were here so they could be able to be a part of this.”

But the students made their presence felt from afar. They took to social media to object to the curfew, and then when they learned on Tuesday that law enforcement personnel were being housed on their campus, they lodged complaints through news outlets and joined a petition demanding that ECSU remove law enforcement from on-campus housing.

The university released a statement on Wednesday, saying, “As a public University, ECSU has an obligation to support other public agencies in times of need, just as we count on their help when the campus makes a request.”

The university announced on Friday that law enforcement officers would leave campus the next day. Now students are joining a call directed at the city and county. A Change.org petition circulated by many students on social media says that “HBCUs should not be asked to provide support to law enforcement while they silence, pacify, and brutalize protestors fighting for Black Lives!”

“Students are the ones that, historically, make the most changes,” Cole said. “It’s so unfortunate that the students did have to go home, because I’m sure some of them wanted to be here. But they are at a distance, and they’re letting their voices be heard.”

Melissa Stuckey, a history professor at ECSU, has become a leading resource on Elizabeth City history since joining the university four years ago. She said the university has a rich history of activism. Notably, ECSU students joined lunch counter protests one week after the Greensboro Four.

In 1963, hundreds of students from ECSU and local high schools picketed downtown demanding that all businesses desegregate.

Far earlier, Stuckey points to Annie E. Jones, a 1901 graduate of the university and a teacher and principal in the city’s schools. Jones worked covertly for Black women’s suffrage, and after the 19th Amendment was passed, she organized literacy classes to prepare Black women to pass literacy tests that had been designed to disenfranchise the Black vote.

“I think that we can see our roots of being strong, Black activists even before the Civil Rights Movement, when I think about women like her,” Stuckey said.

The university is now preparing the next generation of activists, which she says includes understanding the history of Elizabeth City and the surrounding area. It’s not enough to know dates and events, she says. Stuckey wants her students to understand how events connect to each other and see the impacts of social and political changes over time.

She talks about the urban renewal movement in the city in the 1960s and 1970s, and how this led to many buildings that housed Black businesses now lying vacant. She talks about one of the historical Black neighborhoods in the city, just adjacent to the university. It’s the neighborhood where Andrew Brown Jr. grew up, and a drive through it finds several vacant lots, where the city came into possession of land and has not redeveloped it.

She wants her students to engage with the history, recognize systemic forces at work, and identify the impacts. That, she hopes, will prepare them to go out in the world and activate changes in society — changes, she says, that can, with some pain, move the city forward.

“And it is painful, because our history is a painful history,” she said. “So our growth is going to include discomfort. And I hope that I’m giving my students the tools and vocabulary and critical thinking skills to interrogate the world that they’re in, to interrogate the past, to make connections where there are connections, and to not make easy connections — not make facile connections, and not just jump from one century to another and assume that they can do that without really critically engaging with everything that’s happening in between.”

“But it’s really important for young people in this region to be able to see themselves in the history that they study, and to see the power that they have — the power that their ancestors had,” she said. “And it’s the reason why I emphasize so much of the local history.”