As Rashid Davis walks the hallways, he points to posters of his students hanging on the walls. Underneath their names and photographs are their various accomplishments, including sports awards, academic awards, and if they transferred to a four-year college or university. Despite having almost 100 students in six different grade levels, many of whom leave campus to take college classes, he knows every student’s name and story. Davis is the founding principal of Pathways in Technology Early College High School in Brooklyn, New York, a school that has generated significant attention and replication over the last eight years due to its innovative model.

Pathways in Technology Early College High School (P-TECH) was founded in Brooklyn in 2011. As an early college, students can take college classes and graduate with an associate degree. What sets P-TECH apart from other early colleges is the intensive collaboration with industry that is baked into the model.

P-TECH Brooklyn was founded as a partnership between the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE), the City University of New York (CUNY), City Tech (CUNY’s designated college of technology), and IBM. According to Davis, the idea for P-TECH grew out of former mayor Michael Bloomberg’s desire to partner with IBM.

“[Bloomberg] really wanted internship opportunities for students, but IBM had only worked with college students and not high school students,” Davis said.

After announcing the partnership in September 2010 on NBC News’ “Education Nation” summit, Bloomberg tasked a steering committee made up of representatives from IBM, CUNY, the NYC DOE, and Davis with bringing the school to life. Luckily, the lead architect on the IBM side, Stanley Litow, was a former Deputy Chancellor of New York City Schools. Given the focus on technology with IBM as the industry partner, CUNY felt City Tech was the best choice to be the college partner.

The city chose Paul Robeson High School in Crown Heights, Brooklyn as the site of the new P-TECH school and received a federal School Improvement Grant to assist with the cost of implementation. P-TECH opened its doors to students in the fall of 2011.

The P-TECH model

The P-TECH mission is to: “Enable students to master the skills that they need to graduate with a no-cost associate degree that will enable them to secure an entry-level position in a growing STEM industry, or to continue and complete study in a four-year higher education institution.”

The school is a 9-14 school, meaning students are enrolled for six years instead of the traditional four. The expectation is that by the end of six years, students have graduated from high school and earned an associate degree, although some students may do this in less time.

Like many early colleges, P-TECH targets historically underserved students. Their student body is majority male and majority black and Hispanic. However, unlike some early colleges, including The STEM Early College at NC A&T, P-TECH does not academically screen their students; they offer open enrollment.

The model has six key tenets, according to P-TECH Brooklyn:

1. “Partnership between school district, higher education partner, and industry

2. Integrated high school and college coursework, linked to industry Skills Map, leading to an industry-recognized, postsecondary degree for all students. Students can graduate in less than six-years, but the model ensures that students have the time and seamless supports necessary to earn their degree

3. Workplace learning strand, including mentoring, worksite visits, speakers, project days, skills-based and paid internships

4. Open enrollment with focus on historically underserved students

5. Cost-free postsecondary degree

6. First-in-line for jobs with industry partners”

‘The power of partnership’

The partnership with industry is a critical part of the P-TECH model and goes beyond simply connecting graduates to jobs. Industry is deeply involved in every aspect of the school, from creating a workplace learning curriculum to mentoring students to providing paid internships.

“The thought is,” Davis explained, “would industry’s involvement be enough to disrupt the outcomes, and particularly from students who are furthest away from the sphere of success … Would immediate access, would immediate opportunity for all students really allow the adults to make students feel empowered, connected to what we were creating? If that could happen, we could then hopefully produce better results.”

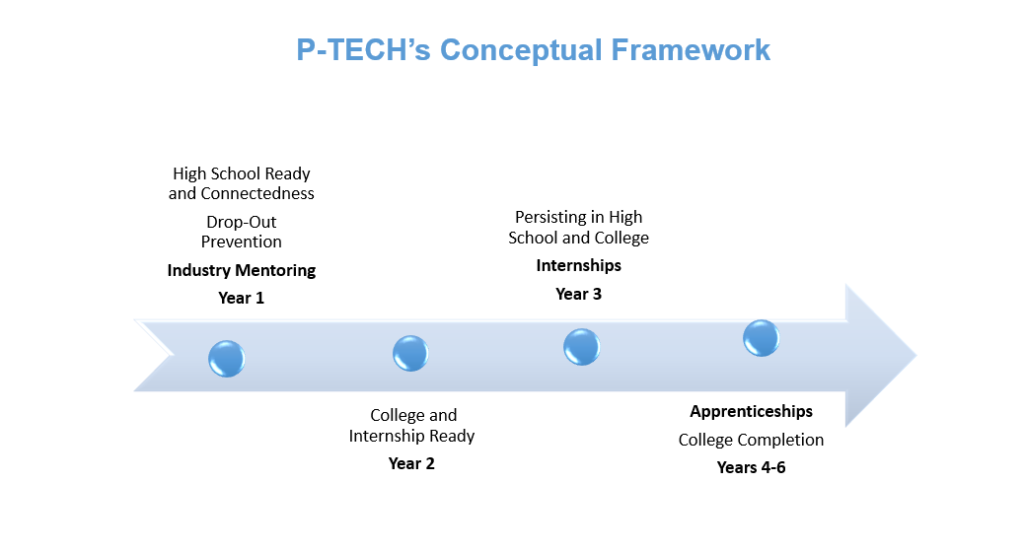

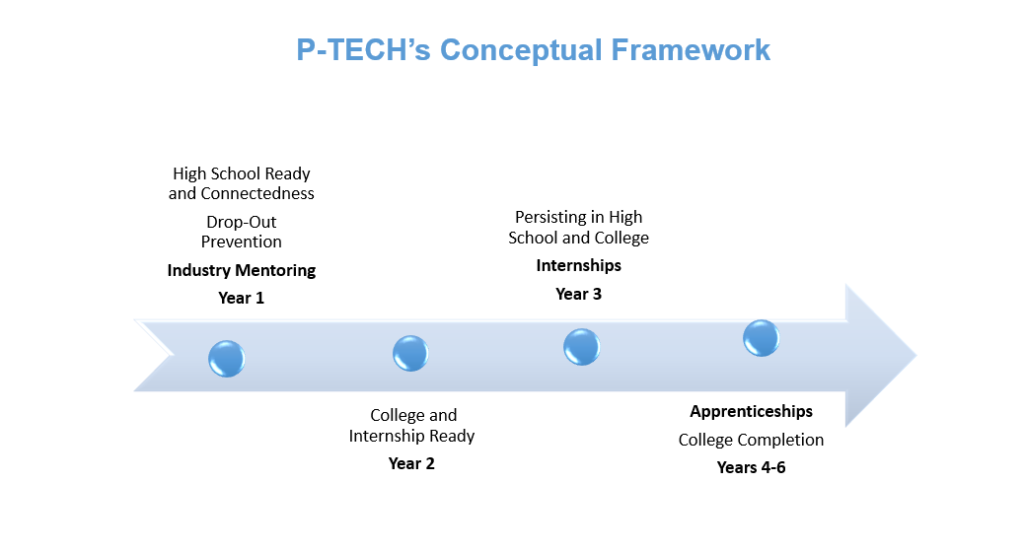

The six years are sequenced to expose students to work experiences in greater amounts as they continue in their education.

“We were really thoughtful from a scope and sequence standpoint, from a design standpoint, and that makes really a world of difference,” Davis said.

In particular, they were thoughtful about connecting industry to students as soon as possible. “We would hope that immediate access to industry would put in place a different sense of motivation,” Davis explained. So, before the end of October, they hold a mentor kickoff event where students get to meet mentors from IBM face to face. As students progress, they take a workplace learning curriculum and eventually have the chance to complete a paid internship in the summer after their junior year.

Yave Delossantos, a senior at P-TECH, completed his internship with the IBM corporate citizenship department. He described his experience: “We work hands on with them. We have mentors. We have managers that appreciate us every day, and that’s a place that we can actually network. This past summer I did the internship, and I could tell you that I would want to do that a million times … I enjoyed every single moment of it.”

Lauwens Joseph, another senior at P-TECH, worked with IBM’s Watson learning and health department, where he worked on an app to help patients going through chemotherapy.

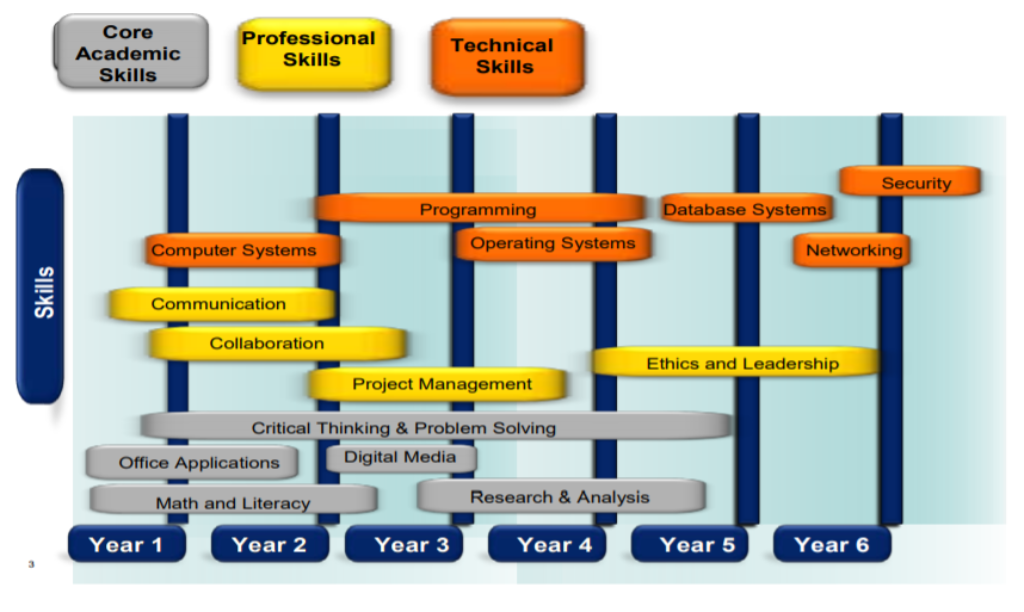

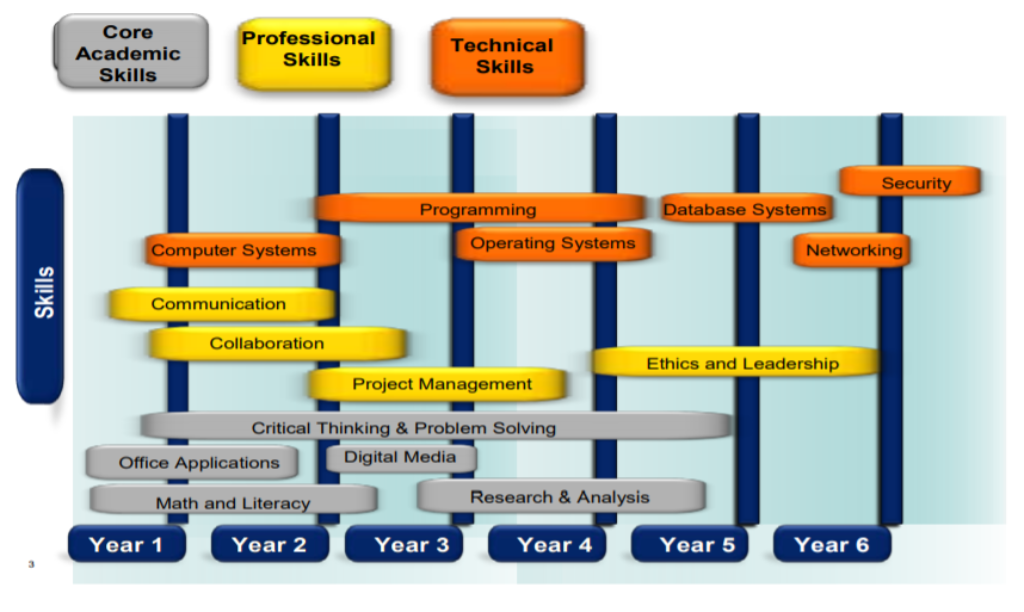

The classes students take throughout their six years is determined by a process called skills mapping.

As described in P-TECH’s skills mapping process guide, skills mapping “is the mechanism that links in-demand jobs with a highly-skilled workforce.” Through backwards mapping, the industry identifies the skills needed for high-wage entry-level jobs with career potential and works with the high school and college partners to create an integrated scope and sequence of secondary and postsecondary work required to master those skills.

At P-TECH Brooklyn, IBM looked at which jobs required an associate degree in applied sciences and had high career potential. They then outlined the tasks required in those jobs and the skills necessary to perform those tasks — including both “hard” skills and “soft” skills.

From there, City Tech determined two associate of applied science degrees that would provide students with the necessary skills for the jobs: Computer Information Systems (CST) and Electromechanical Engineering Technology (EMT). The group worked together to create a scope and sequence of both high school and college classes that would provide students a pathway to earn one of the two associate degrees at the end of six years.

“We weren’t completely starting from scratch,” Davis said. “We were pulling from the best elements of new school work in New York City, what the data was saying nationally, to try to make sure this intersection of high school, college, and industry really could be successful from a design standpoint.”

What does that actually look like? P-TECH is a year-round model with longer school days. Students begin ninth grade with a high dose of English and math classes to ensure they have the foundations for more challenging courses. Workplace, technical, and academic skills are layered throughout the six years in increasing complexity as students take on more challenging coursework and internships, as seen in the image below.

“This school doesn’t waste time,” senior Lauwens Joseph explained. “As soon as you get through the door, they go through any classes you’ve taken before, any credits you have, and map out the correct classes that you should be taking to get through all your high school classes so towards your junior and senior year, you’re only taking college classes.”

Joseph said he likes this approach because it allows him to focus on what he really wants to do.

Results

The P-TECH model has received significant attention across the country and the world. In 2013, President Obama mentioned P-TECH in his State of the Union address. Since the opening of P-TECH Brooklyn in 2011, there are now P-TECH schools in nine states and three countries.

Given the fact that the first cohort of ninth graders from P-TECH Brooklyn completed their six years in 2017, this rapid expansion has largely occurred without much evidence of success. However, now that two cohorts have cycled through the Brooklyn high school, the evidence — which Davis knows like the back of his hand — suggests this model is worth replicating.

To evaluate their outcomes, Davis compares P-TECH Brooklyn’s high school graduation and degree completion rate to New York City and New York state data. According to data from NYU’s Research Alliance, 81 percent of students who entered ninth grade in 2010 in New York City graduated from high school in six years. Additionally, 23 percent of students in New York state completed a two- or four-year degree in six years. These numbers became benchmarks for P-TECH Brooklyn.

“If we could at least, in a 9-14 model, have 81 students finish high school,” Davis said, “and at least 23 students earn the two-year degree, we would be ahead of the game.”

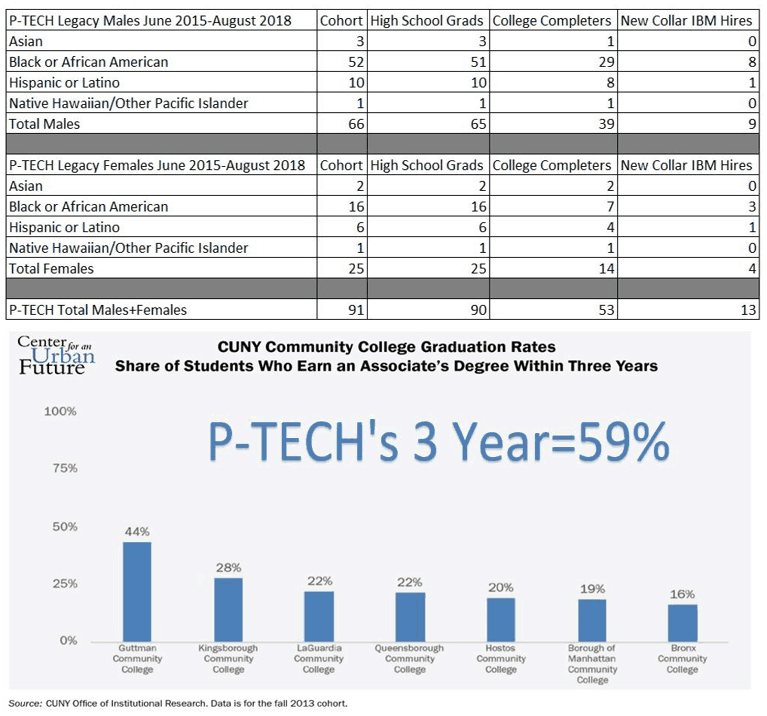

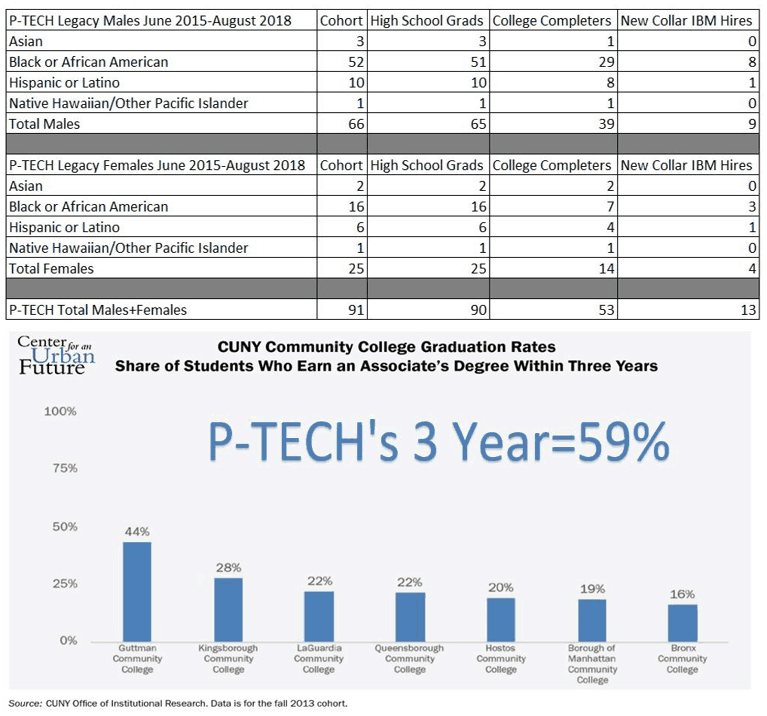

So how are they doing? Of the 91 students who entered P-TECH Brooklyn as ninth graders in 2011 (the first cohort), 99 percent graduated high school in six years. Just over half (53 percent) received an associate degree in applied sciences within six years. IBM went on to hire 13 of these students. For the fall 2012 cohort, 85 percent graduated high school in six years, and 41 percent received an associate degree in applied sciences in that time.

When you compare these degree completion numbers to community college completion rates, the results are even more impressive. The degree completion rate at P-TECH is double the New York state rate of students who complete either an associate or bachelor’s degree within six years, and it is four times the national on-time community college completion rate of 13 percent. Even the highest performing community college in New York, Gutman Community College, has a lower three-year degree completion rate than P-TECH.

Breaking the numbers down by race and ethnicity, black and Hispanic students at P-TECH Brooklyn are far outperforming their peers enrolled in New York’s community colleges. For the fall 2011 cohort, 49 percent of black students and 63 percent of Hispanic students completed an associate degree in six years.

For Davis, he attributes their success so far to a few factors. One of those is ensuring the school leader who is going to implement the design is at the table during the design phase. “Involving leadership in design is crucial because you need support on the ground level for the people in the school,” he said.

Staying true to the design is important, Davis said, because it can minimize implicit biases. “If you’re true to the design, that can minimize the biases that people don’t talk enough about. So if we truly are going to follow this design, we say students that meet the benchmark, they go into college classes because that’s what we designed,” Davis explained.

Consistency of communication between different partners is also crucial. To aide that communication, P-TECH has two liaisons, one for industry and one for college, who spend the bulk of their time at the school assisting students and leadership.

The model is replicating so fast, Davis said he can hardly keep up with the number of P-TECH schools out there. And it will likely continue to do so, as more states and countries see this as a viable way to educate historically underserved students and fill critical skills gaps. For Davis, he will continue to review the data and iterate his model towards the goal of every student graduating high school and completing an associate degree.