The John M. Belk Endowment and Durham-based nonprofit MDC have partnered to examine the patterns of economic mobility and educational progress in North Carolina to determine who is being successfully prepared for entry and success in the most economically rewarding sectors of the state’s economy. The report, “North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity,” provides data and analysis on these trends and includes a close look at eight localities across the state. This week, EducationNC will be featuring the profiles of five of those communities

This month, in partnership with the John M. Belk Endowment, MDC released a report, “North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity,” examining patterns of economic mobility and educational progress in North Carolina by demography and geography to determine who is being successfully prepared for entry and success in the most economically rewarding sectors of the state’s economy. The analysis focuses on the education-to-career continuum, a critical piece of an infrastructure of opportunity—the myriad systems that must be improved and aligned to prepare ever larger numbers of North Carolinians for family-sustaining work and a better shot at economic wellbeing.

That analysis is paired with a close look at eight localities across the state—Guilford County, Wilkes County, Fayetteville, Vance/Granville/Franklin/Warren counties, Monroe, Wilmington, Western North Carolina, and Pitt County—and sketches out a series of actions that communities across the state can take to strengthen and align these critical systems.

Far too many people in the state are struggling to make ends meet. Even in the most economically dynamic metros like Charlotte and Raleigh, people who grow up in low-income families are more likely to stay there as adults than almost anywhere else in the nation, and only small numbers make it to the middle- or upper-income levels despite thriving labor markets that seem full of opportunity. For young people born in the lowest quintile of the income distribution in Charlotte, for example, 38 percent will stay there as adults, another 31 percent will only move up one quintile, and just 4 percent will make it to the highest quintile.

“Even in the most economically dynamic metros like Charlotte and Raleigh, people who grow up in low-income families are more likely to stay there as adults than almost anywhere else in the nation.”

Other findings in the report are equally troubling:

- Upward mobility in 22 of North Carolina’s 24 regions called “commuting zones” ranks within the bottom quarter nationally—and Charlotte, Raleigh, Fayetteville, and Greensboro rank in the bottom 10 of the nation’s 100 largest commuting zones.

- While mobility varies depending on where people live, only about one-third of children born into North Carolina families making less than $25,000 annually manage to climb into middle and upper income levels as adults.

- Latinos and African Americans are more likely than whites to be in poverty and attain lower levels of education, leaving them less prepared for high-skill, well-paying jobs—and those disparities will increasingly affect North Carolina’s economy as these populations grow to make up a larger proportion of the population.

- A family of one parent and one child needs an income of $21 an hour to cover basic living expenses in North Carolina, yet only 26 percent of full-time jobs pay median earnings of that amount.

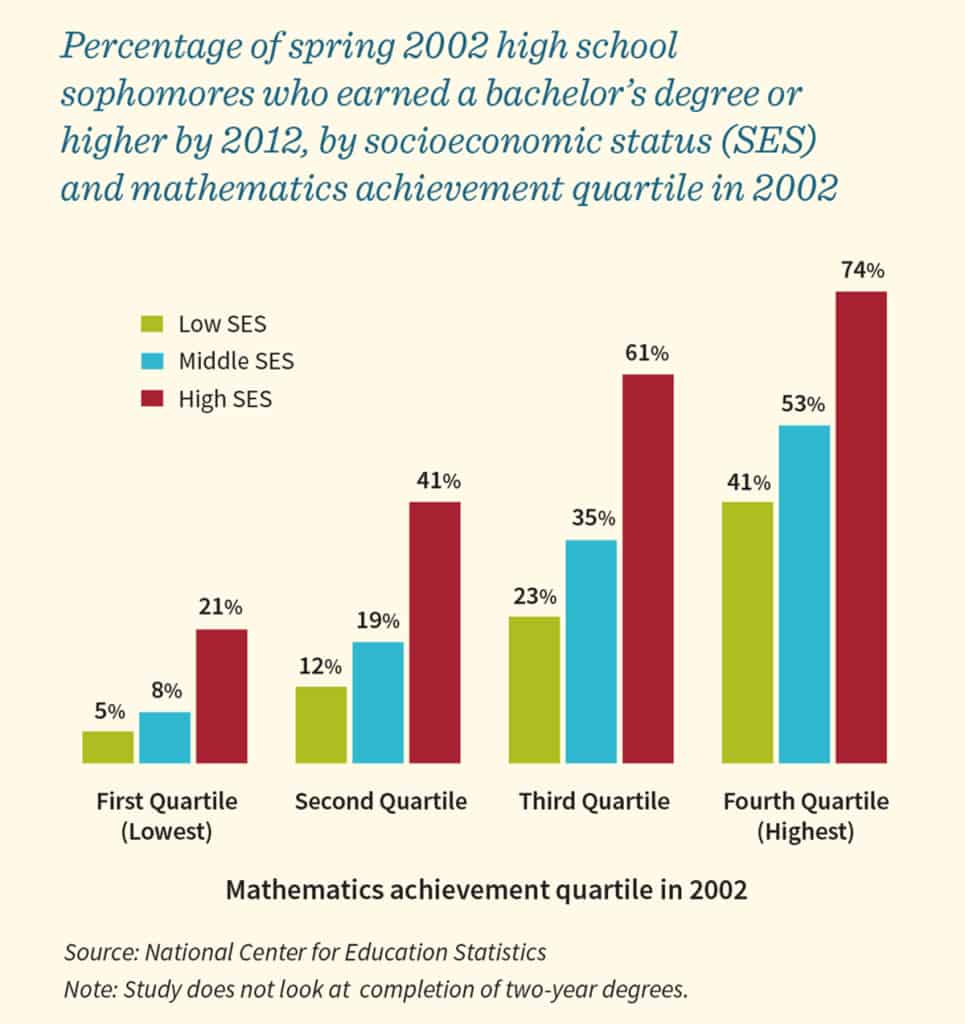

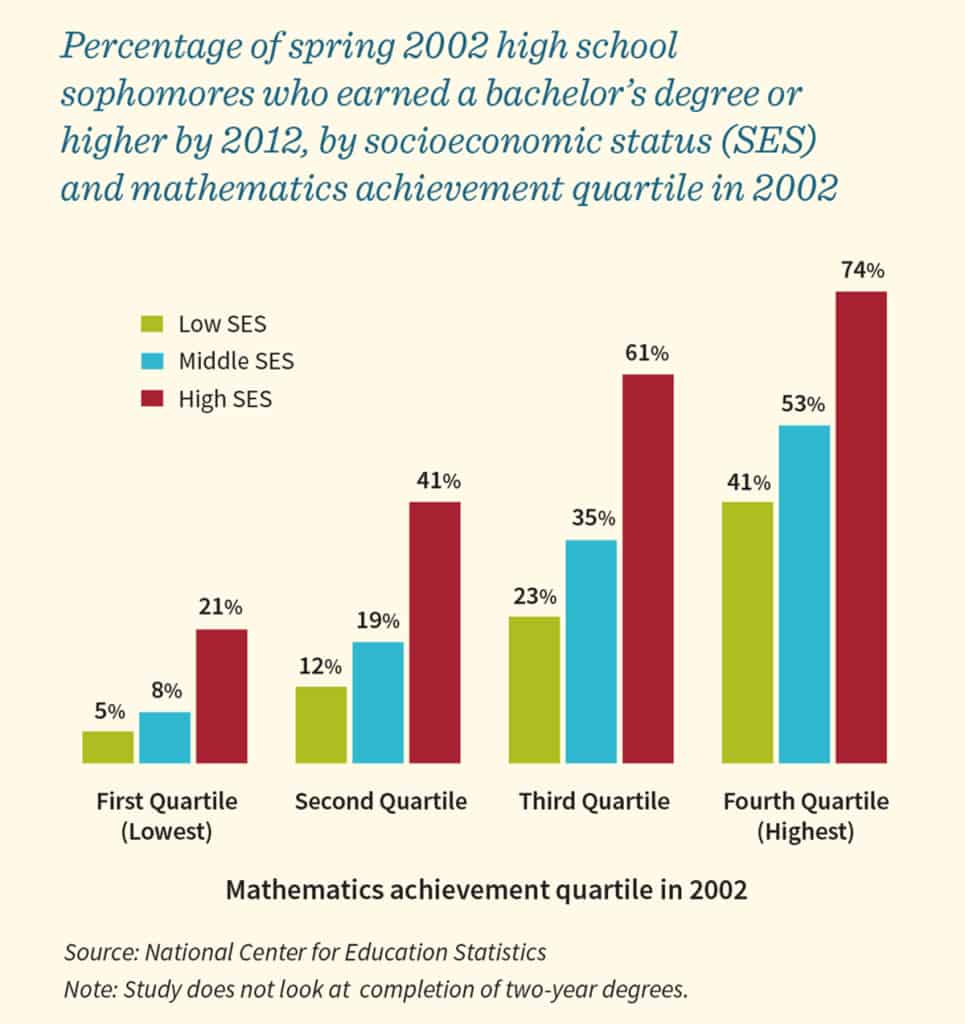

While there is significant variation in mobility levels across North Carolina, no part of the state meets the national average. These mobility patterns, paired with the rapidly changing demographics of the workforce, have significant implications for North Carolina. Gov. Pat McCrory’s postsecondary goal is to ensure that by 2025, 67 percent of North Carolinians will have education and training beyond high school. And there’s good reason for a goal like that: while 31 percent of North Carolinians who attain only a high school degree live in poverty, just 5 percent of people with a bachelor’s degree do. In order to meet the 2025 goal and the competitive demands of a 21st century economy with a skilled workforce, we need to reduce disparate outcomes in education along racial and ethnic lines.

“While 31 percent of North Carolinians who attain only a high school degree live in poverty, just 5 percent of people with a bachelor’s degree do.”

The causes of economic immobility do not exist in a vacuum, but are part of systems that can both ease and impede individuals’ access to opportunities. Improved access can often give them more control over economic outcomes for their families and, in many cases, break the cycle of intergenerational poverty. The creation of an infrastructure of opportunity is beyond the reach of any single institution to create: discrete pockets of excellence are insufficient for changing the trajectory of broad opportunity and improving education and employment outcomes at scale. To move from discrete programming to an aligned infrastructure of opportunity requires:

- Adoption of a guiding framework for communities to assess and create an action plan that is grounded in a common vision of economic productivity and advancement for the community and its people

- Design and implementation of research-based policies and programs that can be scaled for an entire population, hold high expectations for educators, employers, and the workforce

- Maintaining momentum through continuous improvement

- Commitment to providing adequate resources that support the common vision

These are not issues for individuals alone, but for communities and states: If North Carolina’s business and industry are to thrive, it is imperative that the citizenry have the skills and training necessary to thrive, too. This progress has to happen for individuals where they are—in our rural towns and our metropolitan centers. Within the communities we profiled, we saw everything from a rural, four-county region with an intertwined history and economy and limited access to living-wage work with career potential, to a city in one of North Carolina’s fastest growing counties with a diverse manufacturing sector and a growing Hispanic population—and just about everything in between.

We saw efforts that were inspiring in both aspiration and implementation—and many of them are betting on improved education as a way to jump-start change in economic outcomes. In the coming days here at EducationNC, we’ll share stories of some of these North Carolina communities and their commitment to answering the economic imperative with action.

North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity

Part 1–Introduction

Part 2–Cultivating aspirations: Vance, Granville, Franklin, and Warren Counties

Part 3–Partners at the speed of trust: Guilford County

Part 4–Recovery through collaboration: Wilkes County

Part 5–Landscape defines opportunity: Western North Carolina