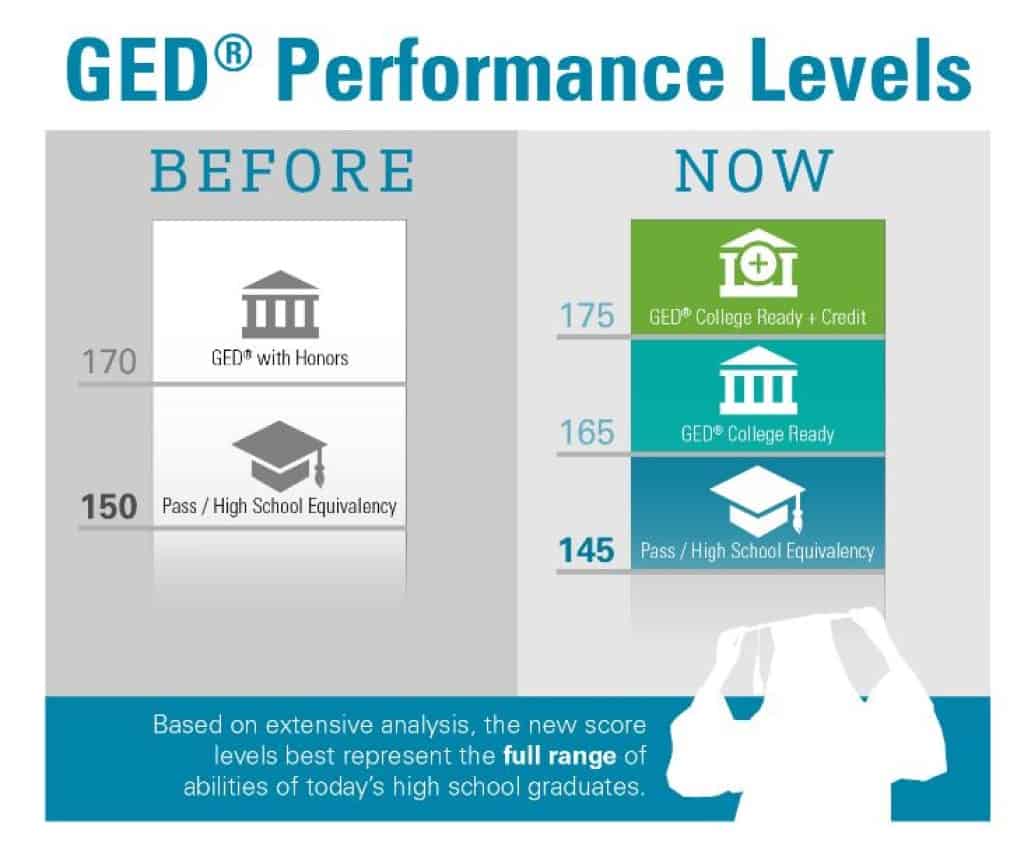

In January, the GED Testing Service announced that they would lower the passing score for the equivalency diploma. Results from the latest version of the test, released in 2014, revealed both lower passing rates and that those who passed the tests were outperforming typical high school graduates in college courses.

Since the test is meant to be equivalent to a high school diploma, the Service opted to change the passing score and recommended that states retroactively apply the new score. States are free to determine how they will apply the new policy. North Carolina, for example, is opting for retroactive; that means almost 800 more North Carolinians will earn a GED.

According the Service’s 2013 Annual Statistical Report, the most recent available on the organization’s website, nearly 21,000 North Carolinians passed the GED test in 2013, representing 1.6 percent of the state’s 1,297,505 adults without a high school credential.

In addition to the new pass score, the Service created two other cut scores: a college ready score and a college ready + credit score. They recommend students who receive these scores be excused from placement tests and/or remedial courses (college ready) or receive college credit in the related course areas.

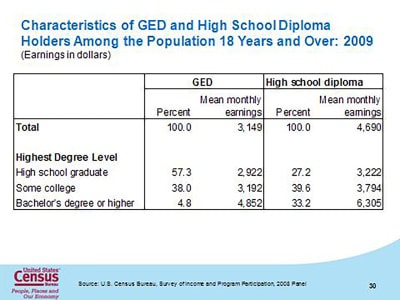

We know that educational attainment has a significant impact on lifetime earnings and economic mobility. In the South, the median income for high school graduates is $26,500. Those with some college education, the median rises to $32,299. For those with a bachelor’s degree, the median income tops out at $48,317.

And in North Carolina, those numbers are slightly lower, with the median income for high school graduates being $26,113. For individuals with some college or postsecondary education, it is $31,193; and for those with a bachelor’s degree, the median income is $45,122.

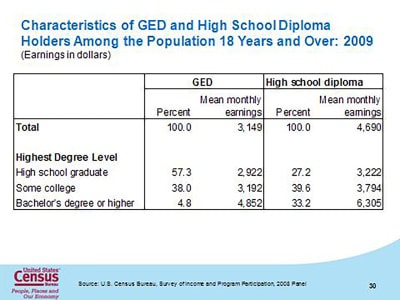

But for GED graduates, postsecondary education and employment outcomes are less than traditional high school graduates.

The U.S. Census Bureau notes that in 2009 only 43 percent of GED earners completed some form of postsecondary attainment, compared to 73 percent of those with a traditional high school diploma.

But alternatives like the GED are critical onramps for those who are not on a typical pathway to economic security—especially in the South where we have half a million young people who are disconnected from work or school, and here in North Carolina, where 38,000 young adults are disconnected, representing seven percent of the state’s population age 16 to 19.

To create conditions for thriving communities, we must encourage individual mobility that rests on a combination of personal drive, deliberately supportive institutional practices, community supports, and the eradication of structural barriers—especially for those who start out furthest from opportunity.

America’s Promise Alliance has identified a critical practice for GED students and recipients: supportive relationships. Though some have posited that these individuals were lacking the non-cognitive skills—self-control, persistence, the now-proverbial grit—Alliance research revealed that no significant difference in these social and emotional competencies existed between GED and traditional diploma youth; rather, it was supportive relationships that were missing—and along with them, the connections to social networks that are vital to securing and excelling in employment. (MDC, the Durham-based nonprofit where I work, has written about these connections here.)

In Don’t Quit on Me, the Alliance explores four types of social support—emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental—and the role each plays in a young person’s development and ability to complete a high school credential and move on to further education and employment. They recommend the following for community leaders who are trying to support young people on this path:

Assess risk and resources of young people in your community

Improve the odds that all young people have access to an anchor [relationship]

Engage health care professionals

Include social support systems

See education and youth services as an economic development investment

They’ve also got discussion guides for educators, grantmakers, policymakers, and others who want to tackle these issues in their own communities. These discussions and relationships will be necessary to help young people—smart, persistent, gritty young people—who have a GED make their way to more education, employment, and economic security.

This article originally appeared at MDC’s State of the South blog. It has been updated and reprinted here with the author’s permission.