This article was originally published by Enlace Latino NC on Sept. 22, 2025. Puedes leer esta historia en español aquí.

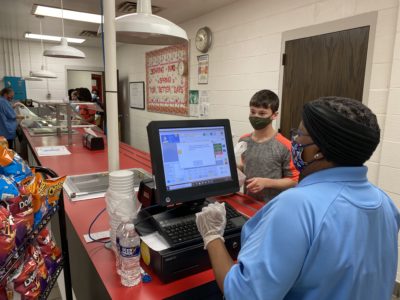

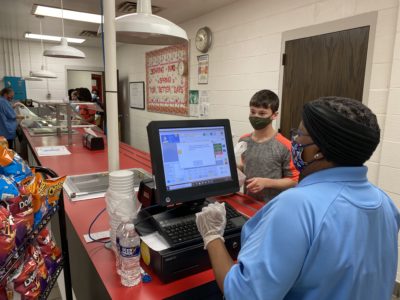

At L. Gilbert Carroll Middle School in Robeson County, Principal Zach Jones watches the lunch line carefully, ensuring every student gets a tray. Many arrive hungry; breakfast and lunch at school may be the only meals they can count on.

“Every morning, every student comes through and gets a plate for breakfast. Even if they don’t eat it, they can share it. The same goes for lunch. That way our students who we know may have some food insecurities, are getting fed,” he said.

Yet the quality and appeal of the meals, factors beyond Jones’ control, determine whether students actually get the nutrition they need.

On a recent Thursday, trays were filled with popcorn chicken, grilled cheese on dinner rolls, canned green beans, Cajun potatoes and fruit ices. Just a year ago, many of those same students were eating locally sourced hamburger patties, collard greens, and in-season berries through the Local Food for Schools Cooperative Agreement program.

Funded by a federal grant that sent $92,304 to Robeson schools and $5.5 million statewide since 2022, the program connected cafeterias with nearby farmers, letting children in North Carolina’s largest rural district eat what their neighbors grew.

But earlier this year, the grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) expired. Now, schools across North Carolina are grappling to meet federal nutrition standards while relying more on bulk suppliers and processed foods. The shift threatens children’s nutrition and puts added strain on an already fragile market for local farmers.

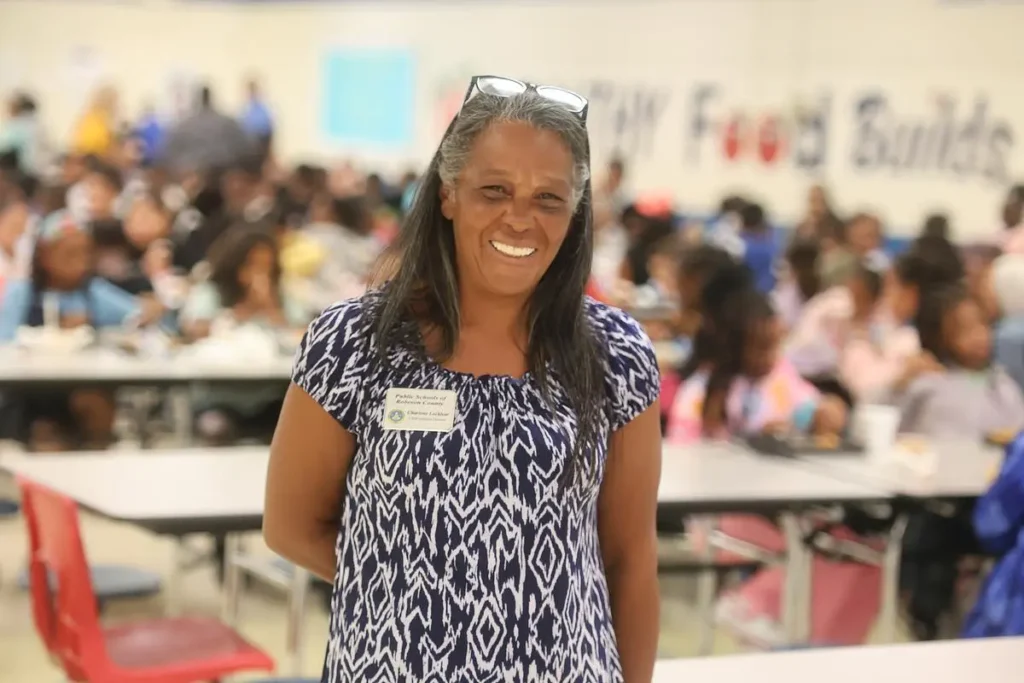

“We were heartbroken, truly,” said Charlene Locklear, Robeson County’s school nutrition director. “The kids really noticed. They’d ask, ‘When are we getting that other patty back?’”

A frontline against hunger

Food insecurity is acute in rural areas: about 16% of rural Americans and nearly 13% of all North Carolinians report struggling to afford consistent meals, according to an Associated Press analysis of U.S. Census Bureau and Feeding America data.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture will stop collecting and releasing statistics on food insecurity after October 2025, saying the numbers had become “overly politicized.”

In some of the rural counties hit by the loss of federal funds, food insecurity rates appear to surpass the statewide average: 21.9% in Robeson (25,570 people), 16.9% in Wayne (19,900), 15.5% in Craven (15,680), and 15.1% in Alamance (26,400).

In those schools, cafeterias are more than a meal line. They are a frontline against hunger.

“Good nutrition is essential for kids to have energy, to think clearly, to use their brains for education,” said Jesus Gallardo Martinez, a community health worker at UNC Health. “When school meals are lower in quality, children may struggle to focus, and that impacts their future.”

Gallardo warns that more reliance on commodity foods means diets dominated by shelf-stable starches and ultra-processed proteins — patterns linked to chronic illnesses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol.

“Today’s kids are our future,” he said. “And poor nutrition can leave a lasting mark on the whole community.”

Local farms and better nutrition

The source of the food matters: Meals made from fresh, local ingredients generally contain higher levels of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients than those relying heavily on commodity or processed foods.

Ben Grimes, who runs Dawnbreaker Farms in Orange County, supplied poultry to Durham schools through the USDA Local Food for Schools program.

“They’re out grazing in pasture, moving so much, building up their muscle mass, and eating a diverse array of foods. That all goes into the nutrition of the meat that kids end up eating,” he said.

Studies show pasture-raised meat contains higher levels of omega-3s, vitamins, and antioxidants than conventionally raised, confined livestock. Commodity chickens, raised indoors on mostly genetically engineered corn and soy, offer lower nutritional value.

Stretching every dollar

Large urban districts like Wake and Charlotte-Mecklenburg received the largest USDA Local Food for Schools grants, according to data from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumers Service. In predominantly rural North Carolina counties, where poverty rates are higher than the state’s urban districts, even modest awards had an outsized impact: Wayne County received $75,000; Craven $53,000; and Alamance-Burlington nearly $93,000.

And the state had expected nearly $19 million in federal support this year. Without it, cafeterias in rural counties are already scaling back, said Spencer Brown, the nutrition director in Alamance-Burlington. High schools that once offered four entrée choices now serve three, and salads appear less often.

“Fresh fruits and vegetables are a lot more expensive,” Brown said. “Without the grant, we’re leaning more on USDA commodities: canned corn, frozen carrots, even processed chicken products. We’re not eliminating fresh food, but we’re limiting it.”

Even at the height of the program, schools relied on those USDA commodities. The difference, Brown said, was that the grant gave directors a chance to swap in apples from the next county or beef raised along the same bus routes children rode to school.

Parents worry as cafeteria options dwindle

In Wayne County at Tommy’s Road Elementary in Goldsboro, Sunday Williams said her 10-year-old daughter often brings lunch from home, unimpressed by the cafeteria choices.

Breakfast at school, though, is harder to replace. Her daughter isn’t hungry until she arrives, and that first meal at school still shapes the rest of her day.

“Having a good option there makes a difference,” Williams said. She acknowledged that meals while the school had the Local Food for Schools program weren’t always appealing, but worried the quality could decline without it.

In neighboring counties, parents are already voicing concerns. On a Duplin County Facebook group, mothers described cafeteria meals as “highly processed microwave shortcuts,” with children often defaulting to peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

“How do you even justify not feeding the kids healthy food?” Williams said. “Some people do not have that option. They can’t pack their lunch every day.”

In her county, as in other rural corners of the state, poverty runs deep. Nearly every school qualifies for federal Title I funding, which supports schools with many low-income students, and thousands of families face food insecurity, said Cathy Larsen, a parent and community advocate.

“For many kids, school food is the only food they can count on,” Larsen said. “That makes the quality really important.”

Related reads

A Washington program, here and gone

The funding that once paid for the healthier meals began as part of a pandemic-era effort to strengthen local food supply chains. The Biden administration directed more than $1 billion in grants to states, helping schools, food banks and distribution hubs buy fresh, minimally processed food from over 8,000 farmers.

In December, another $1.1 billion was announced for the Local Food Purchase Assistance and Local Foods for Schools programs, drawn from the USDA’s Commodity Credit Corporation, a fund controlled by the agriculture secretary.

But earlier this year, USDA allowed the programs to lapse. A USDA spokesperson said the Biden administration “inflated statutory programs with Commodity Credit Corporation dollars without any plans for long-term solutions,” and continued to cite the pandemic “even in 2024” to justify new funding.

Some school officials said they were stunned to see the USDA program vanish, noting that it appeared to align with President Donald Trump’s priorities.

“We have a new administration that is heavily discussing the importance of local and ‘buy American.’ So if they really believe in what they are telling us, why defund programs that support buying local?” said Lauren Weyand, nutrition director in Craven County.

Weyand had just returned from a national school nutrition conference in San Antonio. She remembers the USDA’s top food official, James C. Miller, touting numbers from the podium: nearly 30 million students served, 7.4 million breakfasts and lunches, and billions of dollars flowing through school nutrition budgets. What struck her most, she said, was how much of that money had gone to farmers like those in her county.

“What I would like USDA to do is recognize what those numbers mean for our local economy,” Weyand said.

At the state level, Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler, a Republican, called the termination “disappointing,” noting that the federal program had connected local farmers, produce, and schools.

“We know students and our farm community benefit from local foods in schools,” he said in a statement.

The sudden cutoff was a blow to both farmers and kids, said Grimes, who runs Dawnbreaker Farms in Orange County. His farm had supplied about 2,500 chickens annually, a third of his flock, to Durham schools through the USDA program, earning roughly $25,000 per year from the contract.

Without the Food for Schools program, Grimes said, he’s had to scramble to replace the lost business, relying more on direct retail and home delivery.

“We stood up and we hit the target that they needed. And I think that they let me down,” said Grimes. “It was frustrating, disappointing for me that the farms and small farms stepped up, and the institution wasn’t able to step up. I also say they let down the kids, here we had kids who were actually getting healthy food for once in the school system.”

A state-level stopgap?

With federal support gone, the focus has shifted to Raleigh. Advocates and lawmakers from both parties have voiced support for a $2.5 million farm-to-school appropriation now before the General Assembly, with Troxler calling it “a step in the right direction.”

Some see the loss of federal dollars as an opportunity. Jon Sanders of the John Locke Foundation, a North Carolina conservative think tank, argues that Washington’s involvement could discourage private-sector and community innovation.

“If the government takes over doing something, then to a lot of people’s minds, it becomes that government’s province, and then there’s not as much pushing and prodding from the private sector to try to solve something that everyone regards as a problem,” he said. Sanders points to North Carolina’s Farm to School program, philanthropy, and entrepreneurship as potential ways to fill the gap.

Abby Emanuelson, executive director of School Meals for All NC, said the coalition was glad to see $2.5 million for local food procurement included in the proposed state House budget — but emphasized it was only a starting point. Under the proposal, about 70% of the funds would go directly to local food purchases and 30% to technical support such as storage, transportation, and kitchen training.

“We aim to be broader than just fruits and vegetables,” she added, noting that schools are also interested in local beef and grains. “This fund could help fill the gap left by the loss of federal programs. It’s about ensuring kids have access to fresh, local food, and farmers have a stable market.”

The challenge, she noted, is compounded by recent cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program under the federal “One Big Beautiful Bill.” This legislation is projected to place a $420 million financial burden on North Carolina’s budget, along with shifting additional administrative costs for federal programs to the state.

“That’s a lot of money for this North Carolina legislature,” she said.

Currently, the USDA reimburses $3.43 for each student who eats a free meal, said Weyand, Craven County nutrition director. Even a small state-level incentive for meals that use local produce would help, she added.

“What North Carolina can do is maybe add an additional ten cents on every meal that is served to students, that has a local component in that meal,” Weyand said. “That will make school nutrition professionals and directors continue to want to support local when there’s an additional monetary incentive involved to help offset costs.”

The state funding, however, is just a fraction of the nearly $19 million in federal support through Local Food for Schools that school districts were slated to receive this year. Locklear, nutrition director from Robeson County, said she would love to see the program come back.

“This was more like them assisting us to be able to provide that higher quality product. I think that it is really important that they look at the overall program and how we are utilizing our funds and helping to fill in some gaps of where we are struggling with the reimbursement that we receive,” Locklear said.

Parents, too, are hoping for change. Williams said she would feel great if lawmakers followed through with new funding. But she and her husband, Armando Iniguez, remain concerned about what will end up on their daughter’s tray each day.

“It’s kind of hard to teach your kid healthy eating habits and then send them to school where they’re getting pizza and hot dogs,” Iniguez said.

Associated Press data reporter Kasturi Pananjady contributed to this report. This reporting is part of a series called Sowing Resilience, a collaboration between the Institute for Nonprofit News’ Rural News Network and The Associated Press. Nine nonprofit newsrooms were involved: The Beacon, Capital B, Enlace Latino NC, Investigate Midwest, The Jefferson County Beacon, KOSU, Louisville Public Media, The Maine Monitor, and MinnPost. The Rural News Network is funded by Google News Initiative and Knight Foundation, among others.

Recommended reading