This is the first in a series of articles we will present over the next year examining non-academic supports for students in North Carolina. Future articles will look into the Whole Child NC advisory committee’s work and pilot programs in districts across the state.

It was 6:30 a.m., with the August sun barely breaking the horizon and much of Transylvania County still in darkness. Missy Ellenberger heard her phone ringing and looked at the screen. Carrie Norris, curriculum director for Transylvania County Schools, was calling.

Many years before, Norris was a principal and assistant principal in the district — the type of leader who got to know her students and their families. And in such a small place, she had formed deep relationships with much of the community.

Norris’s voice was heavy as she greeted Ellenberger, who is the student services director for the district.

Her news was bad. A high school student, one Norris had in elementary school, died by suicide.

“And it was just shock in that moment,” Ellenberger recalled. “I went straight to the school, got with the counselors, and it was like, ‘We’ve got to get together, and we’ve got to get to work right now.’ So I didn’t really have time to process the feelings at all.”

That time wouldn’t come until the evening, and then it would come fast and hard.

“How did we not see this coming?” she remembers thinking.

A few achingly short days later, more bad news came — this time from Ellenberger’s husband, a detective with the Transylvania County Sheriff’s Office. Another student had died by suicide.

“It was just complete devastation,” Ellenberger said. “And then it turns into a fear of, is this going to be a trend? These two so close together that were not connected at all. … And so you just are holding your breath and praying that you don’t ever see this again in your lifetime.”

In Transylvania County, the blow came suddenly, in the opening weeks of this school year, and successively, in a way that knocks the wind out of you when you were already breathless. But the response was swift, too, and the district already had programs and practices to use.

But Transylvania isn’t the only place where kids — and adults — are struggling with mental health issues as the pandemic months creep onward. And while the county’s response is indicative of the resilience of people, it also reflects some of the challenges facing the whole state.

How are the kids doing?

Nationally, research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that hospitals across the country saw a 24% increase in mental health emergency visits by children ages 5-11, and a 31% increase for students 12-17 in the first months of the pandemic. The surge compounded an already pressing mental health crisis, with youth suicide rates increasing more than 50% between 2007 and 2017, also according to the CDC.

In North Carolina, the most recent survey data show that high school students are at increasing risk of self-harm, suicidal ideation, depression, and bullying. These findings are from the latest Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), taken in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic. The state conducts the survey every odd-numbered year, with the 2021 collection having begun this month with hopes of finishing by December.

“I think what’s most important [to remember] about the survey is this is an opportunity for our students to have a voice,” Ellen Essick, DPI’s section chief for NC Healthy Schools and Specialized Instructional Support, told the State Board of Education in August.

“We have a lot of data sources that talk about students, this is a data source where students do the talking and they tell us what their health behaviors are and what they need.”

The sample of more than 3,000 students responding to the 2019 YRBS suggest kids are experiencing depression at higher rates. The survey asked whether students “felt sad or hopeless almost every day for two or more weeks in a row during the past 12 months.” The percentage of “yes” answers in 2019 was higher than from any of the past three surveys.

When the respondents were broken down by the grades they received, it suggested a connection between depression and academic achievement — 53% of students making mostly D’s and F’s felt this way, followed by 44% of students making mostly C’s, 36% of students making mostly B’s, and 31% of students making mostly A’s.

Ellenberger doesn’t need the data to see that the days are harder on everyone in school buildings right now. She trusts her eyes, and she speaks with both the kids and the educators.

“I was just at a couple of schools and, yeah, teachers are just tired. Students are tired,” Ellenberger said. “The kids, when I see them walk in the halls, they seem happy to be back at school. They’re wearing their masks like they’re supposed to. But I know there’s some internal struggles for a lot of them. And, you know, teachers, they do what they do because they love kids. They’re putting their best foot forward for the kids. But they’re struggling, too.”

The CDC promotes a Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model to address student health. In 2016, North Carolina’s State Board of Education passed a Whole Child resolution based on this model, and subsequently framed its strategic plan around a whole child approach. But resolutions and strategic plans lack the teeth of law.

When the National Association of State Boards of Education conducted a survey in 2019, it found that only two states and the District of Columbia had codified policy to implement the model. It noted that North Carolina addressed the Whole Child model, but without including it in law.

Last year, the North Carolina General Assembly did pass a school mental health law that directed the State Board to adopt a mental health policy for schools. The law requires that schools adopt mental health plans and requires schools, at minimum, to provide mental health training to teachers and develop suicide risk referral protocols.

Gov. Roy Cooper signed the bill into law last June, but the law did not include funding for these initiatives. The General Assembly’s proposed budgets do not, either. In Transylvania County, the schools are funding projects using federal COVID-19 relief dollars, so long as they last.

What’s working at the district level

When Ellenberger describes what’s working in the district, she keeps coming back to a couple of terms: restorative practices and relationships. They’re part of the district’s emphasis on social-emotional learning, she said.

The work begins with the district’s Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) team, Ellenberger said. MTSS is a framework that schools use to input multiple data sets and work out a picture of a student who might be struggling — academically or with behavior. Ideally, small teams of administrators, counselors, and teachers meet to discuss what they’re seeing and find targeted interventions and supports for those students.

Ellenberger said the district works to support schools so that using MTSS doesn’t feel like checking a box. The question she always asks is, “How are we actually using the things that we’re putting in place to help kids?”

When the district created its “mental health improvement plan” as directed by the state, it worked off a template provided by DPI. Ellenberger said she was heartened to see that many of the practices from the template were already in place in her district.

Teachers are encouraged to focus on restorative practices, which might look like affirmations or check-ins with students to see how they are feeling, but also might look like blocks of 20 to 30 minutes where teachers and students talk about issues or students take SEL screeners.

The district is allowing each school to choose its own SEL screener, a set of questions designed to identify whether kids show signs of things like suicidal ideation, depression, or anxiety. Three of the schools are using Panorama, a technology that pulls key student information into one place and offers teachers visual dashboards and guidance on interpreting data and taking action.

After student data are collected, teams including administrators, counselors, and teachers look at the information and determine next steps — whether it’s monitoring a student’s anxiety level or referring the child to counseling.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

The state doesn’t expressly provide funding for these such programs, so the district is using its Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds. It’s also using ESSER funds to put more counselors in schools. This year, the district was able to fund an additional counselor in two of its nine schools.

“Our ratios, across the state, are way off as far as the number of students that a counselor serves,” Ellenberger said. “And at some of our bigger schools, we were able to add an additional counselor, which has been a lifesaver because the needs are just higher this year. You can tell, they couldn’t be doing what they’re doing if they did not have them there.”

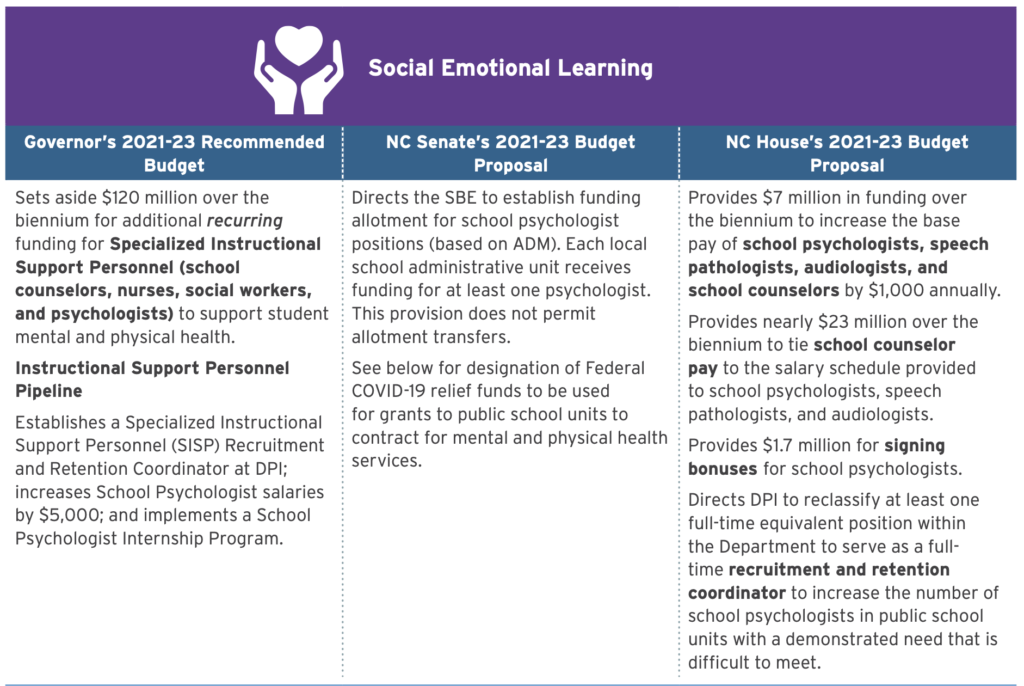

For several years, the State Board has received an annual report on student support personnel in schools and learned that the ratios do not meet the national recommendations. Some areas struggle because there aren’t enough counselors available, while others lack the funding. Cooper’s proposed budget calls for allocating $120 million for hiring nurses, school counselors, social workers, and psychologists as part of fulfilling the court-ordered Leandro plan. The House and Senate proposals stop well short.

Here’s a comparison of the three budgets, from the Public School Forum’s analysis of the proposals.

In the meantime, in Transylvania County, a partnership with Blue Ridge Community Health Services is helping. BRCHS provides two counselors, one in Brevard and one in Rosman, who travel to the schools to meet with students. That’s been a fruitful partnership, Ellenberger said, but one with its own challenges.

“Obviously, we would love to have one in every school, but that’s just not feasible right now,” she said. “It’s so challenging to find therapists that want to do this work. So that’s a real struggle I know that they have had.”

Much of the work after the two tragedies at the beginning of the school year has been emphasizing practices already in place, Ellenberger said. But two new initiatives have sprung up. One is a parent advisory network, begun after a group of parents approached the district with a desire to get involved. The district is still working out its vision for this group, but it will focus on engaging families.

The other is a Social-Emotional Advisory Committee at the district level, which is a team of 12 teachers across the county who will hold their first meeting this month.

“We’ll come together and say, ‘OK, here’s our social-emotional improvement plan. Let’s make it a living document,” Ellenberger said. “And with that group, really get to the nitty-gritty of, what do you see that our kids need? And what do our teachers need?”

Holding onto the wins

Ellenberger said the district is also trying to hold onto the everyday victories — the kinds that won’t get headlines. They’re moments like when a teacher has invested so much in a child — asking about their life and checking on how they feel — that a bond of trust develops.

That bond takes time, but Ellenberger said she recently got a reminder of how powerful it is. She recalled a student who felt so comfortable with their teacher that the student hung back after class and opened up. The teacher quickly realized professional help was needed and walked the student to the counselor. That student is now receiving regular counseling sessions, attending school regularly, and performing well.

“I think, honestly, we have those wins daily,” Ellenberger said. “This is not something that you really hear about, or talk about if you’re not in the student services world. But teachers are definitely making a difference because they’re learning how to use the restorative practices.”

Ellenberger says she’s not an expert and doesn’t have all the answers. She’s learning and working to find solutions, she says. She’ll do whatever she can to prevent future tragedies, just as she’d give anything if there was something she could do to prevent the two that happened. And she says she feels the same commitment from the school leaders and teachers in her district.

“I keep telling folks, ‘I know you’re saying we’re reacting, we’re reacting,'” she said. “But maybe we’re also being proactive for some other child. So we keep moving forward on that.”

Recommended reading