Many dogs only have one owner. Some are lucky if they get a family. Ruby’s family has upwards of 270 people. She is part of a unique program at Harris Middle School in Spruce Pine, North Carolina.

Roughly 70% of the school’s students qualify for free- and reduced-price lunch. And principal Michael Tountasakis says that’s only part of the issues that his students deal with.

“We are in a demographic that has a good deal of generational poverty, and we have a great deal of kids that would score high on ACEs — adverse childhood experiences,” he said.

Tountasakis knew that he had a lot of kids who had suffered from trauma, and while instituting some of the more conventional strategies for dealing with that, he wondered if there was another way: low cost, high impact.

He and his staff had been thinking for a while about how great it would be if they could bring their dogs to school. He knew about the benefits of dogs to mental well-being and just as a source of comfort, but he didn’t want to take his pet idea and push it on the school.

“It would have just been me trying to get a dog into school because I’m a dog lover,” he said. “That’s not really the way to go about it.”

Then, one day, he saw a news program. It talked about how many schools in New York City had instituted a comfort dog program, where they had a canine pal on campus to act as a source of comfort and reassurance to students. All of a sudden, Tountasakis had his in.

“If they can pull it off, why not a small, rural school in North Carolina?” he asked.

Before lunch that day, he’d already called the school featured in the report, as well as administration in the New York City school district. From there, he had conversations with Yale University’s Mutt-i-grees program, the originator of the curriculum used in New York City.

It took eight months to get the program approved. Tountasakis went before the local school board and the district superintendent, showing them endless presentations and introducing them to the research behind the program. He even brought a therapy dog to some of his meetings. Everybody would say hi and pet it. And then, Tountasakis would say to them: “You know how you feel right now? That’s what I want for my kids.”

Finally, he got approval for the program. But even before that happened, he found Ruby.

Tountasakis was at the local animal shelter one day when someone brought in a little black fur ball (in Tountasakis’s words) and asked if someone could hold her while they filled out some paperwork. Tountasakis said he could, and while he cuddled the creature, he realized he might have found his dog.

This is the first year Ruby has been at the school. She sits in the office and students come in throughout the day just to pet her. It not only gives them exposure to a source of comfort, but also more exposure to the principal.

“There are multiple ways that I interact differently now as a result of Ruby being here,” Tountasakis said.

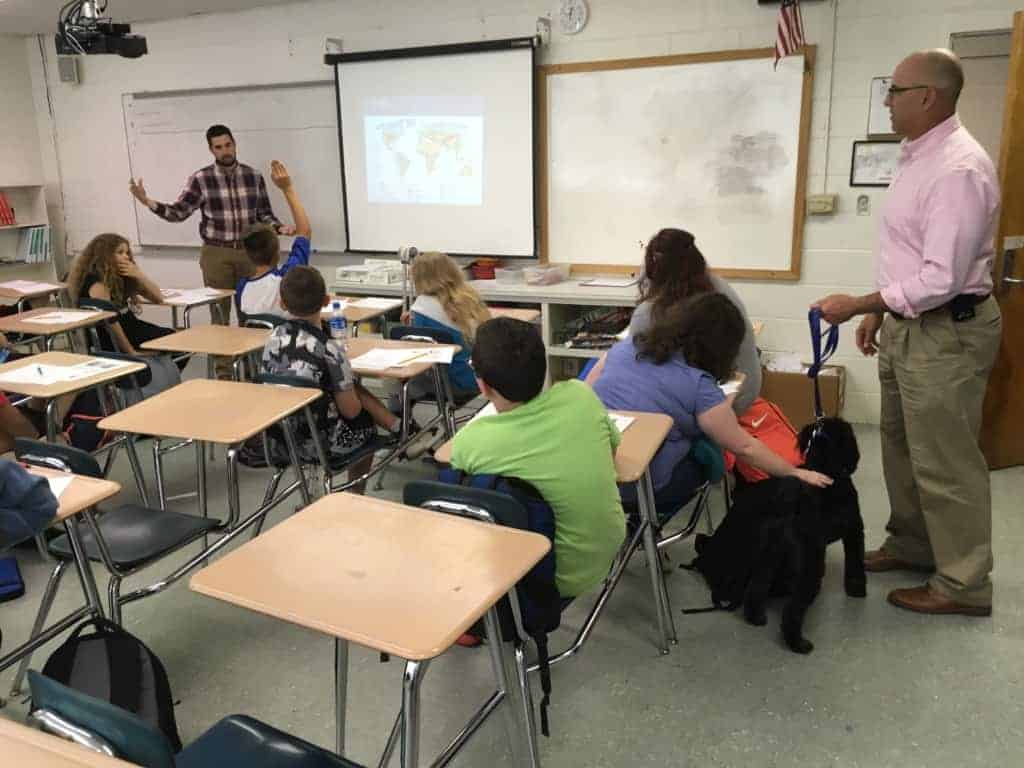

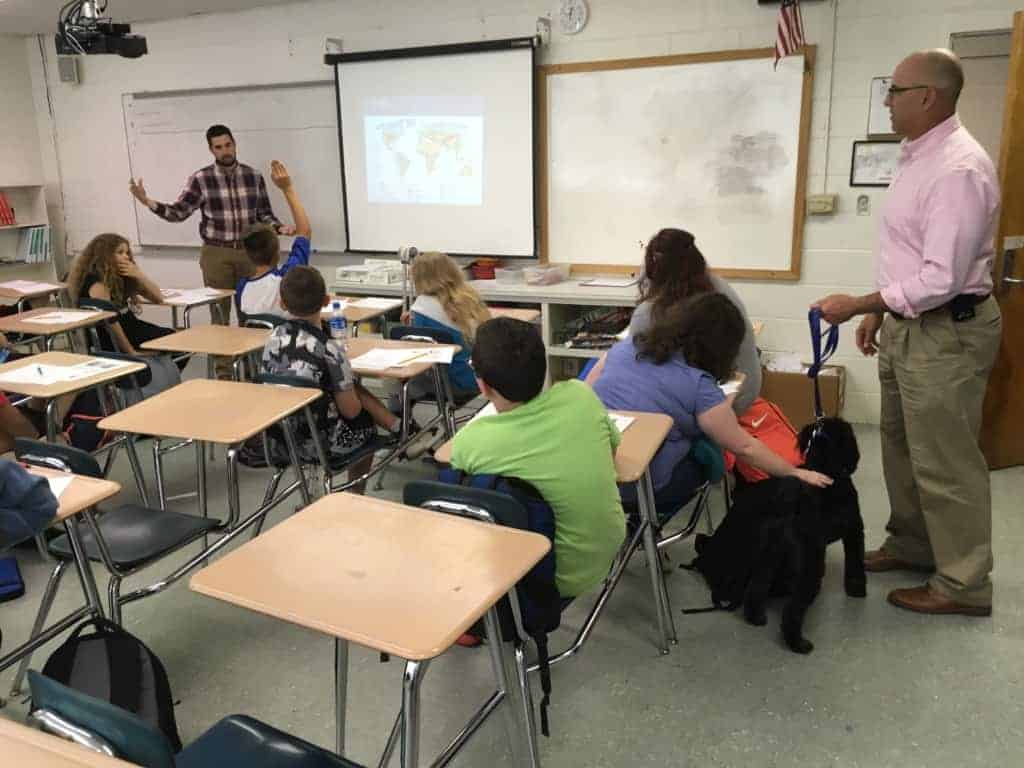

He also takes the dog from class to class throughout the day. Students will keep their eyes on the teacher while reaching out a hand to pet Ruby. She is there for arrival in the morning and during dismissal at the end of the school day. She hangs around during certain small reading groups, and counselor Matt Hollifield even uses her in some of his counseling sessions.

Hollifield is a half-time counselor — Harris Middle School has to share him with another school. Hollifield said that Ruby has been instrumental in getting through to some of his students. Mitchell County, where the school is located, has a lot of poverty as well as issues with opioid and meth abuse. Hollifield said that domestic violence, neglect, and trauma related to poverty are just a few of the issues his students deal with.

“And when you get a middle schooler who’s upset, sometimes it’s hard to get them to talk,” he said.

“I will let Ruby come with me when a kid comes in upset and I really don’t say a lot. Because they’re not going to talk. And they definitely don’t want me giving them 100 questions.”

But as Ruby sits there with the student, they become calmer, their blood pressure comes down, and sometimes, without any prodding, they start talking.

“That dog comes in and I don’t have to say a word,” Hollifield said.

Of course, Ruby doesn’t live at the school. Her real adoptive mom is Sandy Vaughn, the school’s administrative assistant. Tountasakis had been trying to get her a dog for a while. Her two sons are grown and have moved out of the house, and she had an 18-year-old dog nearing the end of its life. Tountasakis said he even tried to give her a puppy almost a year ago.

When he found Ruby, the first idea was for him to adopt her. But he brought her to school one day and Vaughn fell in love with her.

“So I said well, here’s the deal … I’ll relinquish my claim on this dog on one condition: If we get this program approved, you have to bring her to work every day. And that’s a great deal,” Tountasakis said.

Ruby has become part of the school family, and even builds relationships with the wider community. Vaughn said it’s not just the students who want to see her.

“We have parents who come in and ask to see her while they’re waiting for their child,” she said.

And Ruby loves the attention. Tountasakis said she starts to get antsy when she knows it’s time to visit the students. On her first day at the school, Tountasakis brought her around from class to class to introduce her to the student body.

“The message I gave to the student body is this is our puppy and we’re going to raise her together,” he said.

And it’s clear, as she goes up to each student, or students come in to the principal’s office to visit her, that they consider her theirs as much as any parent would.

Tountasakis has zero regrets about bringing Ruby to the school. And Ruby seems as happy as any dog in a loving home. As year one wraps up, the students at Harris Middle look forward to many more years with a new best friend.

“The climate here is better because we have a dog,” Tountasakis said. “And it’s a good dog. And we’re very purposeful in how we do this thing.”