The U.S. military faced a new threat to national security toward the end of the 20th century. This threat affected the recruitment and retention of our nation’s armed forces, reducing their capacity to defend the denizens of the United States and our interests overseas.

The threat wasn’t the Cold War; it wasn’t tension in the Middle East; and it wasn’t international or domestic terrorism.

The threat was a lack of affordable, accessible, high-quality child care.

The makeup of the armed forces changed following the shift from a national draft to an all-volunteer military after the war in Vietnam. More service members had families in the late 1970s and 1980s — many of them with young children. And many more of those families included two working parents than in previous decades.

The child care crisis faced by the military 40 to 50 years ago was similar to the one civilians face today. More families with working parents increased the demand for child care. Thousands of children languished on waitlists, forcing families to consider forms of supervision that lacked consistent standards for safety, teacher training, student/teacher ratios, and curricula. Teachers were poorly compensated, and turnover was high.

Back then, as now, parents couldn’t afford the fees necessary to cover the costs of addressing these challenges, and limited public investment wasn’t enough to fill the gap.

Because the child care crisis was seen as a threat to the collective future of Americans, elected officials took action. Congress passed the Military Child Care Act of 1989, which put a priority on affordability, accessibility, and quality in child care for service members.

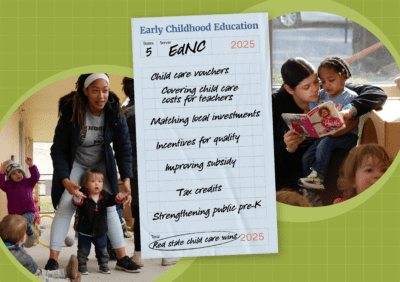

With the end of child care stabilization efforts that were undertaken during the pandemic, North Carolinians now face a similar threat to our own collective future. The military’s approach offers lessons for where we can go from here, in our communities and across our state.

An experiment in universal child care

The Military Child Care Act wasn’t the first time the military had taken the lead on child care. During World War II, women entered the workforce in massive numbers, filling the roles of men who were drafted to serve in the military. This raised the question of who would care for children when both parents were working outside the home to defend American interests.

Congress responded with the Lanham Act of 1940, creating a nationwide, universal child care system to support working families with children through age 12. Federal grants were issued to communities that demonstrated their need for child care related to parents working in the defense industry.

The program distributed $1.4 billion (in 2025 dollars) between 1943 and 1946 to more than 600 communities in 47 states. The grants could be used to build and maintain child care facilities, train and compensate teachers, and provide meals to students.

In his 2017 analysis of the Lanham Act’s outcomes for mothers and children, Chris M. Herbst, of Arizona State University’s School of Public Affairs, found that “the Lanham Act increased maternal employment several years after the program was dismantled.”

Herbst also found that “children exposed to the program were more likely to be employed, to have higher earnings, and to be less likely to receive cash assistance as adults.”

One lesson Herbst took from his research was that the Lanham Act was successful because of the broad support it received from parents, advocates for education and women, and employers. He noted: “Each group was committed to its success because something larger was at stake.”

Today’s military-operated child care model

While the Lanham Act was a short-lived national experiment that hasn’t received much study, the military’s child care program since adoption of the Military Child Care Act of 1989 has become a widely acclaimed model for publicly subsidized early care and learning, serving about 200,000 children each year.

Four categories of child care are available through military-operated child care programs: Child Development Centers (CDCs), Family Child Care (FCC), 24/7 Centers, and School Aged Care (SAC). The official military child care website describes each program type:

- Child Development Centers (CDCs) — CDCs provide child care services for infants, pretoddlers, toddlers, and preschoolers. They operate Monday through Friday during standard work hours, and depending on the location offer full-day, part-day, and hourly care.

- Family Child Care (FCC) — Family child care is provided by qualified child care professionals in their homes. Designed for infants through school agers, each FCC provider determines what care they offer, which may include full-day, part-day, school year, summer camp, 24/7, and extended care.

- 24/7 Centers — 24/7 Centers provide child care for infants through school age children in a home-like setting during both traditional and non-traditional hours on a regular basis. The program is designed to support watch standers or shift workers who work rotating or non-traditional schedules (i.e., evenings, overnights, and weekends).

- School Aged Care (SAC) — School age care is facility-based care for children from the start of kindergarten through the end of the summer after seventh grade. This program type operates Monday through Friday during standard work hours. SAC programs provide both School Year Care and Summer Camp.

Requirements for military-operated child care programs are typically more stringent than state requirements. For one thing, they must be accredited by one of the following: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), National Early Childhood Program Accreditation (NECPA), the Council on Accreditation (COA), or the National Accreditation Commission (NAC).

For context, the requirements for licensed child care in North Carolina are relatively stringent compared with other states, but still fall below the requirements for NAEYC accreditation, which is widely recognized as the national standard. Only 110 programs in our state are NAEYC-accredited — many of which are Head Start or military-operated programs — out of about 5,300 total state-licensed programs.

Military-operated child care programs offer families hourly, part-day, full-day, extended, or overnight care, plus afterschool and summer programs.

Fees are on a sliding scale based on income, ranging from $45 to $224 per week.

The maximum rate is on par with the national average for civilian child care in 2023, meaning that almost every family using military-operated child care programs is paying less than the national average for typically higher-quality early care and learning.

The Department of Defense budgeted about $1.8 billion for child care in 2024 — about 0.2% of its $841.4 billion total budget.

Military child care in North Carolina

In addition to military-operated child care programs, service members may be eligible for Military Child Care in Your Neighborhood (MCCYN), a fee assistance program for families who can’t access military-operated child care. MCCYN pays a portion of the cost of enrolling children in early care and learning programs that meet the military’s high-quality standards in their community.

North Carolina is one of 19 locations where military families may be eligible for MCCYN-PLUS, which expands the MCCYN program to child care programs that participate in state or local Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS) in places where nationally accredited care is not available.

Both programs rely on the availability of high-quality child care in civilian communities. That’s a challenge in North Carolina, which was already facing a child care shortage before the pandemic. Our state has lost almost 6% of licensed child care programs since February 2020, with more expected to close because stabilization grants have ended.

According to the NC Military Affairs Commission, there are 12 military bases and more than 130,000 active-duty military members in North Carolina, giving us the fourth-largest active-duty military population in the nation.

In January 2025, Fayetteville Technical Community College hosted the state’s first N.C. Military Community Childcare Summit, organized by the North Carolina Department of Military and Veteran Affairs (NCDMVA) to discuss the problem that military communities are having with access to community-based child care.

The summit culminated in a screening of Take Care, a documentary about North Carolina’s child care crisis produced by the state Department of Health and Human Services and featuring EdNC’s early childhood reporter, Liz Bell.

Along similar lines, at the North Carolina Defense Summit in April 2025, the theme was “Spouse Resilience,” and the summit included a panel and presentation on child care.

Higher compensation for higher quality

The issues of spouse resilience and child care are inextricably linked for Angie Mullennix, who works for The Honor Foundation at Fort Bragg, helping members of the U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF) transition to careers in the private sector after their military service.

Mullennix served in the U.S. Army for four years after high school and has previously worked for the Department of Public Instruction as the state military liaison. Her husband recently retired from the SOF himself. They have two teenage children.

“If you look at the number of military spouses in North Carolina who have degrees and credentials and could be in the workforce, from nurses to lawyers, lots of them are staying at home,” Mullennix said.

“A big reason why about 40% of (military) spouses do not work is because of child care not being available to them,” Mullennix said, noting that lack of child care is also a barrier to workforce participation among the civilian population.

Related reading

When Mullennix’s children were under the age of 5, she used hourly child care on base, which was available at no cost when her husband was away on assignment.

“You ask any parent in the world, I don’t care who they are, there’s nothing more important than their child’s safety — then their education,” Mullennix said. “And yet, the two things we think are the most important, we put (their providers) at the lowest pay and ask them to do quality care.”

That’s what sets military child care apart from civilian early care and learning for Mullennix: high quality standards and higher pay for early childhood educators, including benefits. She sees lessons in this for North Carolina.

“You gotta pay them to keep them, there’s no secret behind that,” Mullennix said. “If you pay them high, you can also set the standards really high.”

And because workforce participation — and military readiness — is directly tied to the accessibility and affordability of high-quality child care, not investing in it threatens our collective future.

“North Carolina, or any state that doesn’t offer child care, is shooting itself in the foot,” Mullennix said.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Lessons from military child care

Policymakers at every level who are seeking to end the child care crisis can learn much from the military child care model. One report on the topic offers these lessons:

- Do not be daunted by the task. It is possible to take a woefully inadequate child care system and dramatically improve it.

- Recognize and acknowledge the seriousness of the child care problem and the consequences of inaction.

- Improve quality by establishing and enforcing comprehensive standards, assisting providers in becoming accredited, and enhancing provider compensation and training.

- Keep parent fees affordable through subsidies.

- Expand the availability of all kinds of care by continually assessing unmet need and taking concrete action steps to address it.

- Commit the resources necessary to get the job done.

That report was published 25 years ago by the National Women’s Law Center, but its lessons hold up today. Similar lessons have been highlighted in more recent articles published by The New York Times, The 74 Million, and New America, along with the final report published by Mission: Readiness before the Council for a Strong America dissolved last year.

EdNC ran these lessons by Susan Gale Perry, CEO of Child Care Aware of America, and Linda Smith, director of policy for the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska — and one of the primary architects of the military child care system.

Both agreed these are the right takeaways for policymakers across North Carolina to consider.

Other lessons from EdNC

Lesson 1: Do not be daunted by the task

Gale Perry said the top lesson for her is: “Start where you are, know that change is possible, and have a goal post in mind.”

She pointed out that the military’s goal wasn’t a fully publicly funded child care system. It was a system that acknowledged Americans’ values around the role of parents in raising young children — and paying for their care and education. But also that their employers and the government “have a role in offsetting that cost, so that we can ensure that child care is quality, and it is stable, and that the families can actually afford it.”

Smith said there was no “silver bullet” when she and her colleagues were tasked with solving the military’s child care crisis in the 1990s — and there isn’t one for the civilian child care crisis today.

We had to redo the standards, we had to look at the workforce, we had to look at the health and safety issues, we had to look at the fees and how we could bring those fees down. We had to look at the infrastructure of all of it. We’ve got to start thinking about the interconnectedness of all of these things if we’re going to be successful in this country.

Smith said people think that because she worked for the secretary of defense, “I could just tell all the bases what to do, and that would magically happen, which is so not true. It wasn’t just like we could give an order and everybody jumped.”

She said you just have to start where you are, and move up.

Lesson 2: Acknowledge the seriousness of the problem and the consequences of inaction

“The military understood very early the link between people getting to work and child care,” Smith said.

As the military shifted away from relying on conscription and became a more welcoming workplace for women, the need for child care became evident. Smith described working on a base where children were routinely left in cars when their parents were unexpectedly called into work.

“So (military leaders) really got the connection to their guys going to work very quickly, and I think that we still haven’t all understood that in this country,” Smith said, though she notes businesses have started making that connection since the pandemic.

“The other thing the military understood was that a pilot is every bit as important as the mechanic who works on the plane, and so they invest in all of their people,” Smith said.

She and her team had to design a program that worked for everyone, or it wouldn’t work for anyone.

Lesson 3: Improve quality

Smith said quality was of critical importance when she was designing the military’s child care system in the 1990s, especially after child abuse and neglect scandals that came to light in the 1980s.

She and her team studied the child care standards of all 50 states and created a set of military standards that fell squarely in the middle. Then they set about training the 22,000 early childhood educators they already had — most of whom were military spouses — to meet those standards.

That was a six-month training program. Then there was an 18-month training to get them to move beyond those standards toward national accreditation. They hired highly qualified trainers to work with educators at each site.

“And if you didn’t do it, guess what? You’re fired!” Smith said.

There was an incentive to participate in the training, beyond keeping their jobs — higher compensation.

“Maybe some were grumpy about it, but we didn’t have to fire people,” Smith said.

North Carolina already has some tools in place to help educators advance their education and improve their compensation, specifically through the WAGE$ and TEACH programs — both of which were highlighted in the report that identified these lessons.

“(The military) realized they had to get serious about quality and quality standards. And I would say that’s a lesson for us now, particularly in a climate that is deregulatory,” Gale Perry said. “And while I’m for sensible regulatory reform, I think we have to be really thoughtful about not wanting stacks of child deaths in child care sitting on a desk waiting to be investigated.”

Lesson 4: Keep parent fees affordable through subsidies

Smith said that while designing the military’s child care program, she and her team figured out that there was no way parents could afford the actual cost of high-quality child care. So they set up a subsidized system that would provide a 50% match — on average — to parents’ fees, paid directly to child care programs.

“We had to, on average, match parent fees dollar-for-dollar, with the higher-income people paying more and the lower-income paying less,” Smith said. “So a major, for example, would pay two-thirds of the cost, and a private would pay one-third, but the average was 50/50.”

Smith pointed out that we’re already subsidizing child care in ways that are hidden — through the public benefits and social programs that early childhood educators often rely on because of low compensation, and through lack of workforce participation.

Lesson 5: Expand the availability of all kinds of care

Gale Perry said the military’s model really stands out to her for its ability to assess unmet needs and take action to improve.

“In the early 2000s when there were the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there were a lot of deployments of National Guard and Reserve who did not live on post and did not have access to on-post child care,” Gale Perry said. “That is really when the military got in the business of thinking about, how do we help build capacity and make child care accessible for military families off post?”

That’s when the MCCYN came about, subsidizing high-quality early care and learning in a broader array of settings in the communities where service members live.

Smith said that the Military Child Care Act was originally targeted toward child care centers, but she recalls briefing the assistant secretary of defense on the potential effects of that strategy when they were designing the system:

I remember saying we need to apply all of this to family child care, to school-aged care, to part-day preschools, because if we don’t, all the parents are going to have a demand on these centers that we can’t meet, right? Because if you lower the cost in the centers and you improve the quality, why would somebody go to another place when they get it cheaper and better over here?

She made the case for educators in every setting getting the same access to training and the same level of compensation, because that’s what would work best for everyone.

“Everything applies to everybody,” Smith said. “And I think that was one of the smartest policy decisions we made.”

Lesson 6: Commit the resources necessary to get the job done

“There was this perception that we just had a lot of money and we threw it at” child care, Smith said. But that wasn’t the case.

“When they passed the Military Child Care Act, it didn’t come with an appropriation,” Gale Perry said. “So they had to fight equally hard for the funding, and a lot of the funding actually ended up coming from local base commanders making the decision to invest in child care.”

Now the military submits a budget request to Congress each year, and depends on those appropriations.

For state and local policymakers seeking to solve the civilian child care crisis without public investment, the woman credited with solving the military’s own child care crisis 35 years ago has a message.

“It’s gonna cost. There’s no way it doesn’t cost,” Smith said.

Recommended reading