|

|

The mission of the Center for Child and Family Policy (CCFP) at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy is “improving the well-being of children and families through research, education, and engagement.” Jennifer Lansford has been with the Center since 2000 and recently became its director. EdNC spoke with Lansford about her time at CCFP, her policy goals, and what keeps her up at night. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

EdNC: How did you get interested and invested in policies related to children and family?

Lansford: I am a developmental psychologist by training, and my interests are at the intersection of child development, culture, and policy. Early on one of my frustrations doing pure basic science was, if you got some interesting results, that was interesting from a research perspective, but you thought, “Well, who else cares about that? And how would that actually be useful to anybody?” So for me, it was appealing to take that knowledge and figure out how this could be used in the service of society.

EdNC: Walk us down the path that led you to become the director of CCFP.

Lansford: I have been at Duke with the Center for Child and Family Policy since 2000. For the last 22 years I have served in different roles here, but primarily as a researcher. I’ve worked on a number of studies of child development and parenting, and some evaluations of long-term interventions. But after being here for so many years, it’s fun to take on a new set of responsibilities and opportunities outside of the research that I’ve spent most of the last 22 years doing.

EdNC: What is your highest priority for the center as you settle into your new role as its director?

Lansford: We have three main areas of our mission: teaching and mentoring, research, and engagement or policy outreach. The center is in a good place, so I am hoping to build on what is already a really successful organization. Right now we have an exciting career development series that’s about careers in child and family policy. We have a lot of one-on-one mentoring opportunities for students, and I think those kinds of relationships can be really important, both for students and faculty. We also have a number of ways for students to get involved in the research that’s going on at the center. As far as the research part of our mission, we have a lot of exciting projects going on there too. The research spans a wide range, from evaluating local programs going on in preschools or home visiting for newborns, to international work, and everything in between. It’s exciting to think about these different spheres of research inquiry going on at the local level, at the state level, nationally, internationally. You can make an impact at the intersection of the practice and policy at those different levels. It’s kind of a challenge, but also fun to think about how you would go about doing that through local partnerships, through state partnerships. And some of those partnerships are just figuring out who the stakeholders are, who it makes sense to try to reach.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

EdNC: Some of the policy measures that were put in place to support the child care industry during the pandemic are set to expire soon, causing experts to warn of a looming “child care cliff.” What sort of policies do you think might prevent us from falling off that cliff?

Lansford: I think a big question is how to build systems of care. If I were going to design an optimal system to avoid things like the child care cliff, it would start with universal paid parental leave. Mothers are either demonized or valorized as being the ones who are responsible for figuring out the child care issue, but systems that do [parental leave] well don’t treat this as just a women’s issue. Sweden, for example, designates a certain number of the leave days for fathers. And if the fathers don’t take it, the family loses it; it’s not like it can be then shifted over to the mother. That’s great from a systems perspective because it clearly involves fathers, not just mothers, and that has benefits for kids as well.

EdNC: The U.S. is a long way from having something akin to Sweden’s Nordic model, so what are some alternatives that might work in a place like North Carolina right now?

Lansford: I think there are some things that don’t necessarily require revamping an entire system — some of the credits that happened during the COVID pandemic, for example. It provides a bit of a buffer for families, especially for families who are living in poverty or close to poverty. Having even a small amount of extra funds per month, whether that’s in the form of a tax credit or cash stipend or something like that, can help with food security, it can help prevent evictions, it can prevent losing utilities. Those kinds of things can be expensive when you’re talking about an entire statewide program, but they can also do a lot of good. Other things that are short of the full Nordic model, but could still do some good are extending some of the Family and Medical Leave Act provisions to smaller employers, for example. Anytime businesses are able to offer that kind of flexibility, that’s helpful to children and families. There are also certain business practices that are hard for children and families, such as last-minute scheduling. This often applies to lower-wage hourly workers who are then scrambling to arrange child care because they can’t predict what their work schedule is going to be. And if they don’t get the hours they’re expecting, or their hours vary from week to week, they can’t predict what their income is going to be and they can’t budget. There’s been some movement, I think, on trying to change these practices.

EdNC: What keeps you up at night?

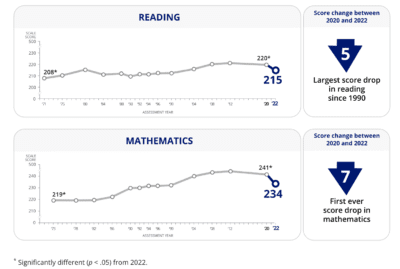

Lansford: From the pandemic perspective, kids are still suffering repercussions from learning loss during the pandemic. The latest national numbers that just came out showed big drops in test scores in reading and math, and bigger growth in disparities than we’ve seen in a long time. It’s going to take a long time to recover both academically, as well as socially and emotionally, from the pandemic. Especially for adolescents, we’re still seeing these really scary rates of mental health problems like suicidal ideation. It’s going to take teachers, families, and communities having some grace with kids, and not expecting them to go back to pre-pandemic levels right away without some extra support. The thing that keeps me up at night, non-pandemic related, is violence against children in general. And some of the violence against kids, it can be due to discrimination against kids. I think about LGBTQ kids who continue, in some states in particular, to really be quite marginalized by state policies. That’s hard for parents who are already trying to help kids through a tough transition, and then for those parents to be accused of maltreating their kids? That stuff breaks my heart.

You can learn more about upcoming CCFP events by contacting Erika Hanzely-Layko, or learn more about CCFP’s research projects by contacting Berkeley Yorkery.

Recommended reading