“The poorer parents are, the less they talk with their children,” was the subtitle of an article in the New Yorker entitled The Talking Cure in 2015. As a retired teacher, this article grabbed my attention. It opened my eyes to why remedial reading classes, however well-intentioned, struggled to overcome the extreme disadvantage children in these classes have with a limited vocabulary. Dana Suskind’s “Thirty Million Words: Building a Child’s Brain” describes how parents can be shown how to “tune in, talk more, and take turns.”

During my 30 years of teaching third- through sixth-graders, I was always disappointed that remedial reading did not succeed in bridging the gap between children entering school with a 650-word vocabulary and their classmates who had 1,000-1,500 word vocabularies. Children were pulled out to attend remedial classes and were understandably not enthused about lining up to go. Critically, they missed what was being taught in their regular classrooms. These remedial classes did not tend to instill a love for reading, which engaging in literature circles can do.

The New Yorker article focused on a grant that Bloomberg had given Providence, Rhode Island to implement LENA (Language Environment Analysis). This article gave me pause, and reminded me of a classroom memory from 1987.

I was teaching sixth grade in South Carolina when “Baby Jessica” fell down the dry well in Texas. The children in my class came to school the next day and told me it was impossible for Jessica to fall in a well. I carefully explained what I had learned on the news before realizing my students thought Jessica was in a whale; they had never heard of a well. This experience brought me up short, and I began to pay closer attention to what other words I used that I assumed my students understood.

Around this time, there was a growing body of evidence about language development in 0- to 3-year-olds. Results of the Perry School Project in Ypsilanti, Michigan from 1962-1967, the Abecedarian Project conducted by the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute from 1972-1985, and the ongoing Child-Parent Center study in Chicago provided longitudinal data on the positive effects of high-quality early care and education.

A statement on the Chicago Child-Parent Center study published by the Glasscock School of Continuing Studies at Rice University states he following:

The Chicago Child Parent Center references both the Abecedarian study and the Perry Preschool study, noting that their “findings square with the Chicago Child Parent study: students enrolled in these studies had a 29 percent higher graduation rate from high school, a 41 percent reduction in enrollment in special education, a 33 percent lower rate of juvenile arrest, a 42 percent lower rate of arrest for violent offense and a 51 percent reduction in child maltreatment. All of which confirms that for every $6,730 required to invest in each child the rewards equate to $47,759 for each participant.”

The success of these three projects resulted in my pursuit of LENA. I contacted Courtney Hawkins in Providence to learn more about what the schools there were doing. She explained how LENA, which targets 0- to 3-year-olds, could increase the vocabulary of children entering preschool. She gave me a contact at LENA, who suggested I contact the Huntsville City Schools system in Alabama as the demographics there are more similar to Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, where I now volunteer as a tutor.

Helen Scott, school readiness director in Huntsville, invited me to observe their LENA Start Program, which uses recorders (not tape recorders) to track parent-child conversational turns. Huntsville schools recruited volunteer participants and have achieved such significant success they no longer have to recruit — parent participants have spread the word.

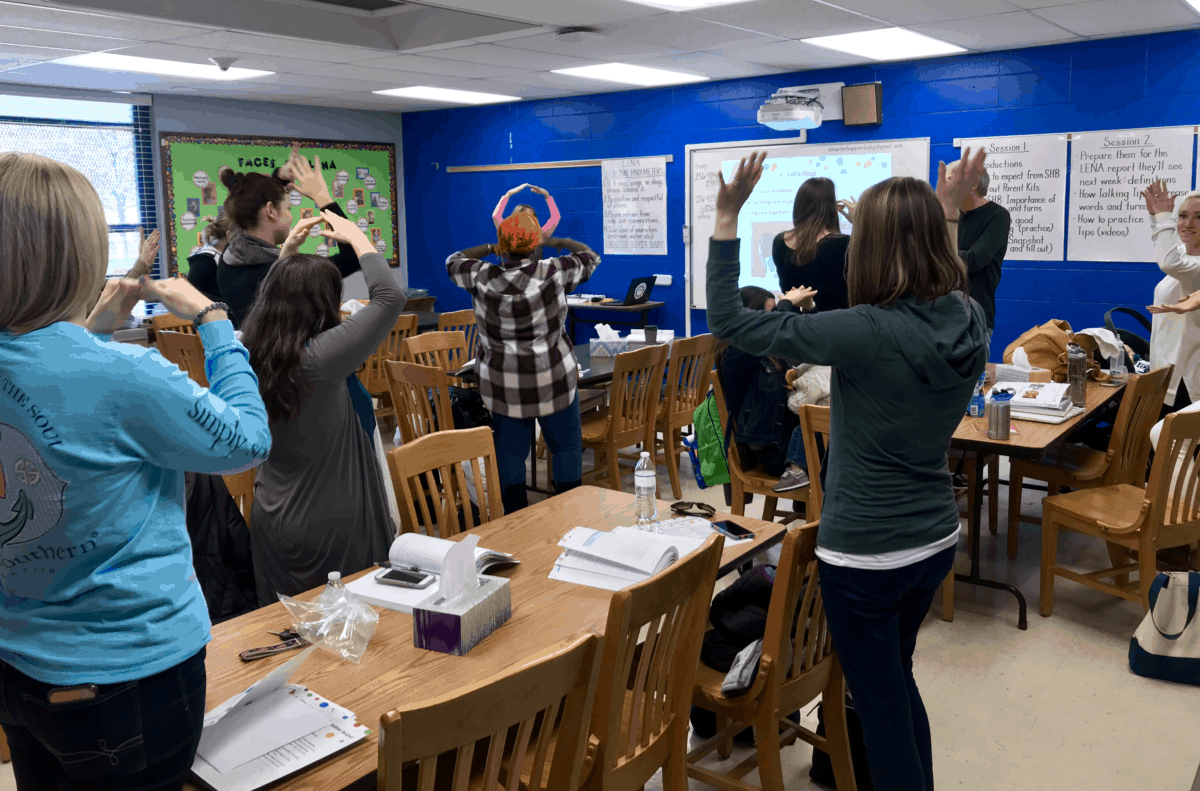

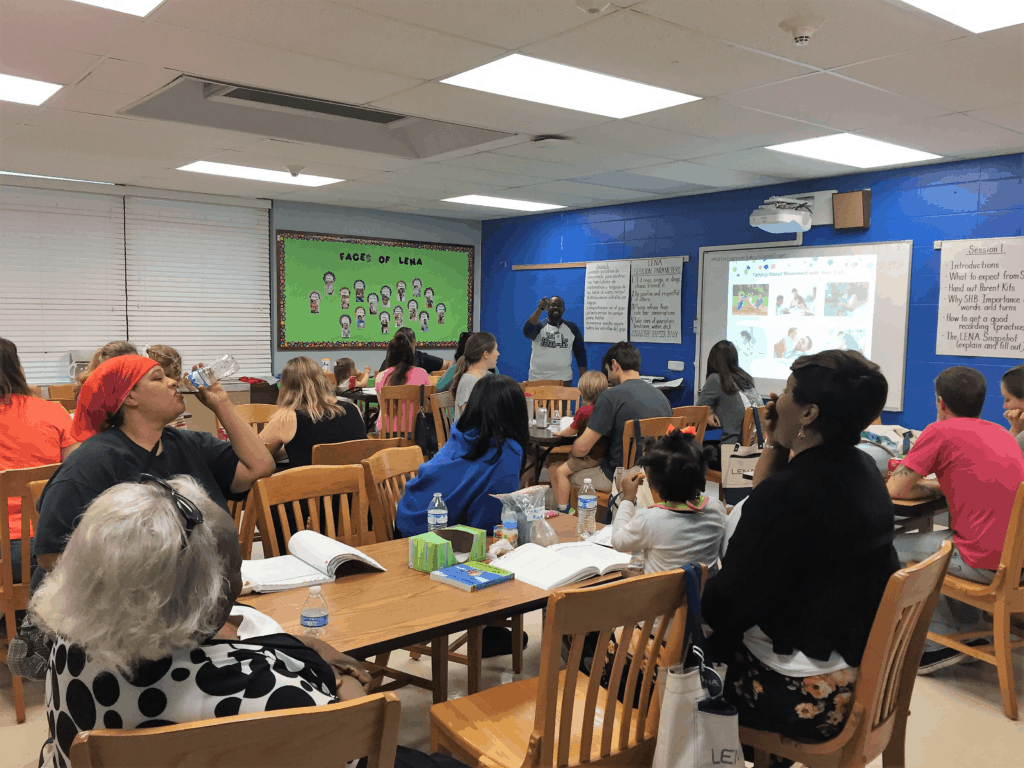

I spent two days in Huntsville, where the staff shared what they were doing and included me in a parent session at a local school. Childcare was provided in a separate room at the school. The parents in attendance enjoyed a meal with other parents of 0- to 3-year-olds, discussed their experiences from the previous week, compared their progress graphs, and engaged attentively in the evening’s video from LENA. At the end of each of the sessions, which were held weekly for 13 weeks, the parents received a new book to put in their child’s library.

For comparison, I also spent a day in Gaffney, South Carolina where the schools were in their third year of using LENA Home, a less expensive program that does not use the recorders. I attended a parent session in a school library and made two home visits with Laura Camp, the coordinator of early childhood education in Cherokee County, South Carolina.

In September 2017, LENA invited me to their conference in Colorado. A myriad of topics were addressed which enhanced my understanding of how effective LENA could be. I also visited the LENA Start program in Greensboro. Participants there were enthusiastic, and suggested a second opportunity to use the recordings to be sure students maintained and improved their progress.

LENA Start works to ensure that the early childhood word gap is closed long before children enter school. This program both empowers parents and gets them actively engaged in their children’s learning from the very beginning. LENA Start has possible economic advantages, too. If children come to school ready, money used for the decades-long and expensive efforts to remediate children could be used to enhance other educational opportunities for all children.

“Paying it Forward: The Economics of Closing the Opportunity Gap,” a talk given at the LENA conference by Flavio Cunha, professor of economics at Rice University, underscored the increasing disparities in income equality. There are huge differences in cognitive skills evident by age 6 between children when divided into groups based on family income. Cunha stressed the need to identify the right tools for all families, as income is not the only factor in student success; the amount of words said to children is also critical. He summed up his talk by stating, “modern economy is more than vocabulary, it is also cognitive ability.”