According to the consent order signed by Judge David Lee, a plan of action for the provision of the constitutional Leandro rights must ensure a system of education that includes “a system of early education that provides access to high-quality pre-kindergarten and other early childhood learning opportunities to ensure that all students at-risk of educational failure, regardless of where they live in the State, enter kindergarten on track for school success.”

This is the foruth piece in a week-long series that will examine each of the components of the Leandro consent order through the lens of schools and communities in North Carolina. Follow along with the entire series here.

An early childhood teacher is asking her 4-year-old Chapel Hill students, in Spanish, how many plates they need at their table.

The students, most of whom are native English speakers, speak only in Spanish in this NC Pre-K classroom at Spanish for Fun Academy, a Spanish-immersion private child care center.

Students are excitedly counting the spots around their family-style dining setup. “Cinco!” “No, seis!”

The Orange County Partnership for Young Children — one of 75 local Smart Start partnerships — makes sure sites like this one are supported, from providing professional development to teachers, to introducing healthy nutritional practices, to funding outdoor learning environments.

Around back, Maria Hitt, the partnership’s program manager for Healthy Starts for Infants and Toddlers, points out that the center has cut the number of trashcans lined up by the side of the building in half by getting rid of paper products for meals. She says the partnership provided the center with a dishwasher to make that possible.

Smart Start partnerships serve as local hubs for early childhood services and centers for young children and their families. In the long-running Leandro case, which established North Carolina’s constitutional obligation to provide every child with a sound, basic education, the path forward includes strengthening the early childhood system across the state.

In a consent order in the case signed in January, Judge David Lee outlined critical needs of the state’s education system, including a “system of early education that provides access to high-quality pre-kindergarten and other early childhood learning opportunities to ensure that all students at-risk of educational failure, regardless of where they live in the State, enter kindergarten on track for school success.”

The consent order also endorsed the findings and recommendations of a report from WestEd, an outside consultant that has been studying how the state should make changes to meet its Leandro obligation since the court commissioned its work in 2018.

In that report’s section on early childhood education (starting on page 87), the group found the system that cares for and educates the state’s youngest children has strong points but needs greater funding, more qualified educators, and broader reach. Both the consent order and the WestEd report specifically mention targeting “at-risk” children and their families with high-quality services and education.

Below, we break down the WestEd recommendations for early learning — scaling up Smart Start, expanding NC Pre-K, aligning early education and elementary settings, and strengthening the early educator pipeline — and examine the state’s status with each of them.

University Child Care Center cares for children of UNC-Chapel Hill employees. Liz Bell/EducationNC

The center is known for its early childhood teacher retention. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Smart Start

Smart Start began in 1993 with the intention of meeting 25% of the early childhood learning need, which the program calculates by using data on child population, cost of care, poverty levels, and existing state and federal funding. The infrastructure met only about 5% of that need in 2018, according to the WestEd report, spending $147 million.

Research from a 2011 Duke University study found that children in counties that received relatively more Smart Start funding than others had higher math and reading scores by the time they reached third grade and were less likely to be placed in special education.

The WestEd report calls for increased overall funding so local partnerships can meet their original intention of 25% of early learning community needs, as well as specific funding to address administrative costs of the 75 local partnerships across the state and start-up costs for new programs.

“With more adequate funding levels, the potential to have significantly greater impact is really phenomenal so that we can ensure children really are developmentally on track when they enter school,” said Donna White, interim president of the NC Partnership for Children, the Smart Start network’s state-level organization.

The report also suggests that Smart Start funding sources are shifted to better support the specific needs of communities.

In about half of counties across the state, local Smart Start partnerships like the one in Orange County administer NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds. Partnerships also support home visiting programs, provide technical assistance in classrooms, and connect families to education, health, food, and counseling resources. They sort out several federal, state, and local funding streams and try to strategically distribute funds to meet the distinctive needs of their communities.

Local partnerships are mandated by statute to spend 70% of funds on early education programs. More flexibility, White said, could lead to better uses of funding, determined by local needs.

“We need to get that flexibility back,” White said, “… to get back to the root of what Smart Start is all about and really ensure that the local-specific strategies that vary from one community to another can be implemented.”

White and Orange County partnership leaders said more funding flexibility would allow partnerships to invest in systems that support children during the first three years of life — the most rapid period of brain development, research shows. White said new funds, as much as possible, would be directed to such services.

“The science is just too clear for us to do otherwise,” White said.

The WestEd report echoes this sentiment, calling for funding and infrastructure changes to support a “robust array of early childhood programs with a high-quality workforce,” pointing to initiatives like home visiting and child care subsidies.

“This statewide early childhood infrastructure that Smart Start has is an envy of other states, and this is a moment for North Carolina,” White said. “We have the knowledge. We have the will. We must take advantage of this opportunity to make North Carolina a great state for children and families and for our prosperity in the future.”

Students at Spanish for Fun are encouraged to serve themselves at lunchtime. Liz Bell/EducationNC

Orange County Partnership is teaching other centers this family-style dining model — as well as other nutrition and health components. Liz Bell/EducationNC

NC Pre-K

The WestEd report says the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, NC Pre-K, has been proven effective but is falling short in its reach.

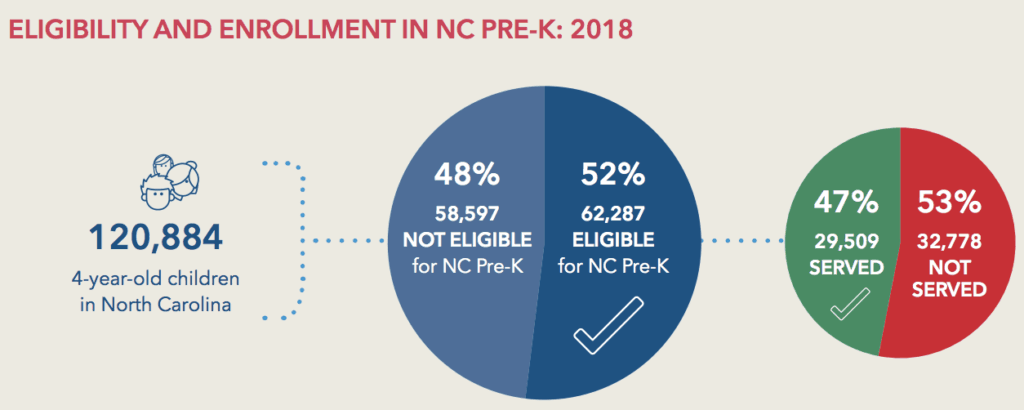

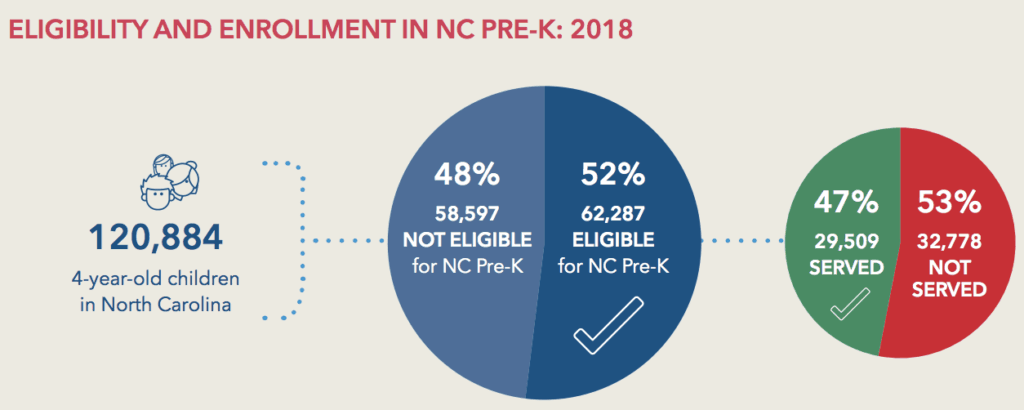

The program, which research has linked to school readiness and academic gains in the early elementary grades, reaches a little less than half of the children who are eligible. Under current eligibility requirements, which are based on income and other factors like military status, English language learning, and special needs, about half of the state’s 4-year-olds are eligible.

In 2018, the legislature committed to adding $9.3 million each year to NC Pre-K from 2019 to 2021 with the goal of eliminating waitlists across the state. More funding for more slots is needed, but the story became trickier than that.

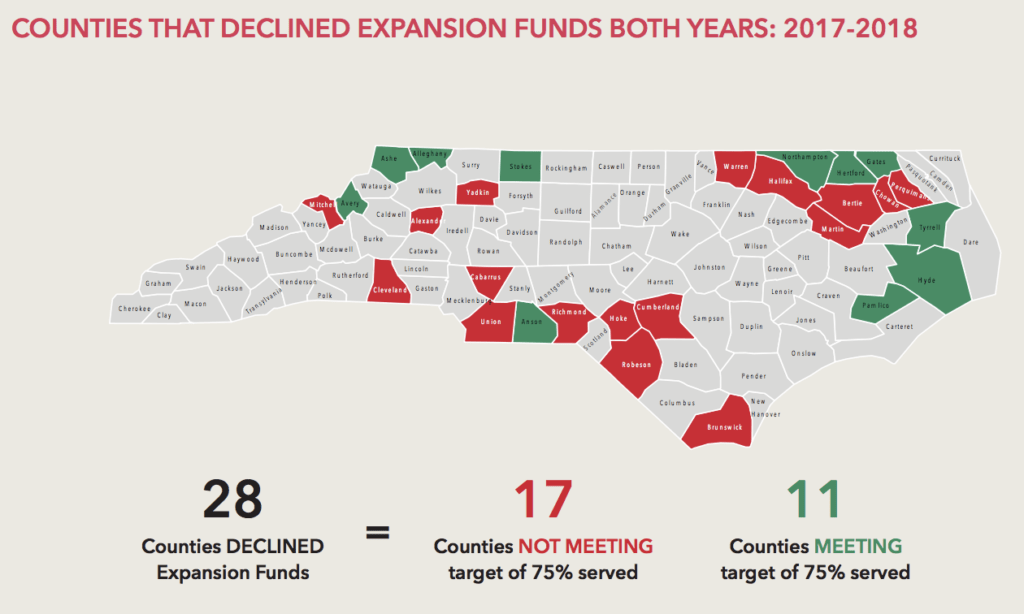

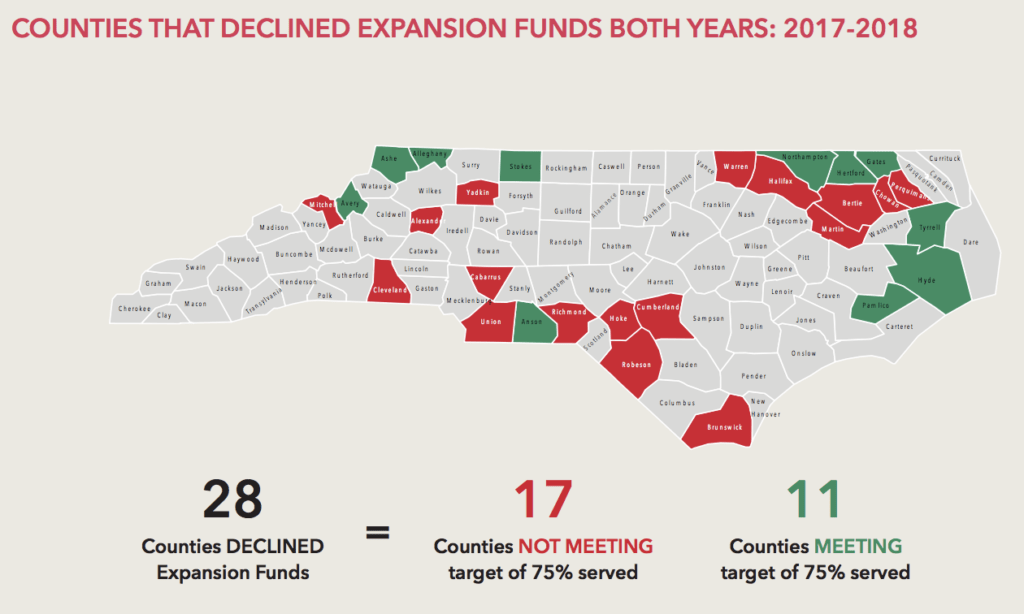

A group of state business leaders commissioned a report to look at why some counties were turning down expansion dollars from the state. That 2018 report from the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) found that 28 counties declined funding for more NC Pre-K slots in both 2017 and 2018, and 17 of those counties were not reaching an enrollment benchmark of 75% of eligible children. Why turn down the money, then?

The same report outlines barriers to serving more children, even with more state funding for slots. First, state funding for each NC Pre-K slot covers only about 60% of the actual cost. Counties must come up with the rest, normally using a mix of federal, state, and local dollars.

And money for slots is only part of the equation. Some counties do not have enough early education programs or centers that meet NC Pre-K standards. Finding enough early childhood teachers with adequate credentials and education levels is another issue. For many families, especially in rural areas, transportation challenges keep them from enrolling their children.

As a result of the NIEER report, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) conducted a legislatively-mandated county-by-county study of challenges facing NC Pre-K programs and barriers to expansion, which has not yet been reported to the legislature. The legislation also asks DHHS to make recommendations based on the results of that study as to how to shift the state’s funding structure.

The WestEd report recommends the state work to knock down these barriers to expansion, focusing first on children in low-income families and communities.

The report calls for expanding the program to care for all at-risk 4-year-olds for the entire day and entire year. It also calls for higher reimbursement rates for NC Pre-K providers to cover administrative costs, the costs of raising quality when necessary, and the cost of keeping programs open longer.

The report also calls for a data-collection process to identify the children and families who need services — and removal of obstacles the NIEER report found: by building new facilities, offering transportation support, and giving financial incentives to four- and five-star private centers in high-poverty areas to offer NC Pre-K and meet the program’s quality standards.

Elementary alignment

The WestEd report found that transitions between the early childhood and elementary environments were disjointed and difficult for children and families.

A state pilot project is working to address lack of communication between those systems by encouraging data sharing and the development of transition plans in certain counties.

At the state level, the B-3 Interagency Council — established in 2017 by the General Assembly — is working to develop better alignment of pre-K and K-12, starting with governance. Members include people from both the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees most of the early childhood system, and the Department of Public Instruction, which oversees K-12 education.

The report calls for pre-K teachers to ease transitions into kindergarten for students and for elementary schools to be ready to take those children. It suggests formative assessments across the systems to create alignment in instruction.

Since 2015, the Kindergarten Entry Assessment has been mandated across the state, requiring kindergarten teachers to fill out information on their students in the first months of the school year. Implementation of that formative assessment has varied among districts and schools.

Once children reach elementary school, the report calls for more teaching assistants, more specialized support personnel such as nurses, psychologists, and social workers, and professional development for elementary principals to better understand early childhood development.

Early childhood teachers

Finally, the WestEd report calls for more qualified early childhood teachers to meet the needs of students and families. That workforce is struggling with low education levels and compensation, and high turnover rates, the report says.

Across the state, early educators are required only to earn credit for a single community college course. In practice, the requirements vary depending on the star rating of the center. NC Pre-K has its own education standards as well. Lead teachers must have a bachelor’s degree and hold a license or be working toward one.

But overall, the report notes that 64% of lead child care teachers did not have an associate or bachelor’s degree in early childhood education in 2015. And 38% did not have an associate or bachelor’s degree of any kind.

Experts say compensation is generally lower and turnover higher for teachers caring for infants and toddlers.

The report recommends identifying how many early childhood teachers are necessary to meet five-year workforce targets to provide early childhood education to all at-risk 4-year-olds. It also urges boosting recruitment efforts such as loan forgiveness and home-grown preparation programs.

The report suggests linking early childhood teacher compensation packages to public school salary schedules and adjusting pay to comparable fields.

For NC Pre-K teachers, the report calls for additional funds to bring salaries for teachers at private centers up to those in classrooms at public schools.

The report also suggests investing in the early childhood teachers now in the classroom to increase quality, through professional development as well as programs from the Child Care Services Association (CCSA) like Infant-Toddler Educator AWARD$ and Child Care WAGE$ that support teachers’ salary growth and further education.

The report calls for fully funding the child care subsidy system and eliminating waitlists. Estimates put the number of children on waitlists for subsidized care across the state at between 30,000 and 40,000.

Supporting early educators in Orange County

Even in a higher-income area, Orange County struggles to get high-quality teachers in its early childhood classrooms.

“Many centers are understaffed, particularly the privates,” Hitt said. “It’s hard for them to compete with the public school system.”

In 2015, the Child Care Services Association found 19% of early childhood teachers in North Carolina were leaving the field within three years of entering.

Most sites in Orange County score four or five stars on the state’s five-star quality rating system for child care centers, said Shawna Daniels, the partnership’s Healthy Starts coordinator. That means most educators at those centers must have at least associate degrees.

Even in higher-quality centers, Daniels said, turnover is an issue, especially in classrooms for infants and toddlers, where pay is often lower. Intensive support is needed to make sure teachers feel supported in their work, have the knowledge they need to do good work, and can ensure a high-quality environment for children, she said.

An initiative called Ready Infant/Toddler Classrooms, which the partnership began funding four years ago through the CCSA, aims to provide that support.

Interactions between teachers and students are measured with a tool called CLASS (Classroom Assessment Scoring System), and professional development is given to teachers through weekly visits. Daniels said that things such as the teacher’s responsiveness to nonverbal cues and level of language-building were observed and scored.

Daniels said getting center directors involved was also important.

“We learned pretty quickly that those classrooms have so much of an emotional need that if administrators are not keyed into that — the teachers being responsive to children emotionally aren’t getting the same support from their administrator— it makes it really hard for them to do their work.”

CCSA, through federal block grant funding obtained by the state, has taken components that are working from the Ready Infant/Toddler Classroom Initiative in Orange County and created a pilot program in other parts of the state — Randolph County, Watauga County, and a nine-county Child Care Resource and Referral region in Alleghany, Ashe, Davidson, Davie, Forsyth, Stokes, Surry, Wilkes and Yadkin.

The Infant & Toddler Technical Assistance Model Pilot Project, over three years, will aim to see how intensive coaching for both teachers and directors, as well as small caseloads for the coaches, can lead to sustainable change in classrooms, said Monnie Griggs, CCSA’s director of technical assistance.

“We want the practices to become part of the culture in the center,” Griggs said.

Professional development, Daniels said, is not the whole answer. She said the early educator workforce needs a shift in outside perception as professionals, as well as more education requirements and better compensation.

“If we don’t have dedicated and educated teachers, then all of the other stuff we’re doing is for naught,” she said. “I mean there’s not going to be adults in the room to make ratios, let alone provide quality education.”

Leandro resources

Everything you need to know about the Leandro litigation by Ann McColl

Sound Basic Education for All: An Action Plan for North Carolina (WestEd Report)

Executive Summary of WestEd’s Report

WestEd’s supporting reports:

- Statewide assessment system

- Statewide accountability system

- Cost adequacy, distribution, and alignment of funding

- Supporting student learning by mitigating student hunger

- High-poverty schools: Assessing needs and opportunities

- School success factors

- Attracting, preparing, supporting, and retaining educational leaders

- Educator supply, demand, and quality

- Developing and supporting teachers

- Best practices to recruit and retain well-prepared teachers

- Retaining and extending the reach of excellent educators

- How teaching and learning conditions affect teacher retention and school performance

Supplement to the Investment Overview and Sequenced Action Plan in the WestEd Report

Judge David Lee’s consent order

Draft priorities from the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education