Assigning letter grades to each and every public school in North Carolina made manifest what educators and policymakers have long known: The standardized test scores in schools filled with students from low-income families fall far below the scores of schools loaded with students of middle-class and affluent families.

Most high-poverty schools got Ds and Fs. Most schools given As and Bs have fewer than half their students from low-income families.

Yes, poverty burdens schools. Now, let’s focus on an equally potent proposition:

Schools fight poverty.

Schools ameliorate the physical sting of poverty by serving as societal feeding stations.

They do so based on the educational rationale that students can’t learn on empty stomachs. Aside from the educational benefits, free and reduced price lunches offer more than half the public school students in North Carolina at least one proper meal each weekday.

In a moving story by Martha Quillen – and a follow-up editorial – The News & Observer emphasized the importance of schools as feeding stations by calling attention to the fact that “snow days can lead to hungry days” for thousands of school children, even in the economically robust Triangle region. In addition, Lou Anne Crumpler, director of No Kid Hungry NC, has pointed out that little more than half of the school children eligible for free breakfast and summer meals programs actually show up for the food.

Ultimately, schools fight poverty by delivering their own most critical service – education itself.

As my friend, the late George Autry, who recruited me from daily journalism to join the nonprofit research firm MDC, used to say repeatedly, “Educated people refuse to be poor.”

For public schools in today’s economy, fighting poverty effectively means preparing young people for, and propelling them into, education and training beyond the 12th grade. Data show wide gaps in pay, in employment, and in poverty rates between adults with no more than a high school diploma and with a college degree.

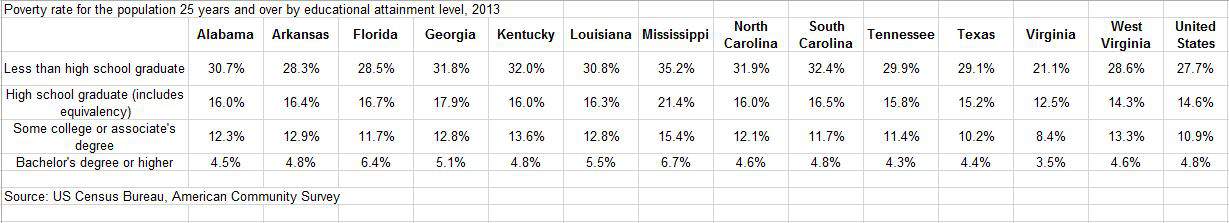

Alyson Zandt, the former Autry Fellow who manages research for MDC’s State of the South publications, provided this illustrative chart (click on chart to enlarge it).

It makes the point that the more education an adult attains, the less likely he or she is to live in poverty. Indeed, the 4.6 percent poverty rate among North Carolinians with a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2013 was somewhat lower than the national rate of 4.8 percent.

One method for increasing the chances that students from low-income circumstances would escape poverty is to wrap them in schools and classrooms with middle- and upper-middle class students.

Considerable research has suggested that mixed-income schools raise educational achievement among lower-income students without diminishing achievement among higher-income students.

Unfortunately, socio-economic integration has grown more difficult. Public support appears soft for school assignments with such integration as a high priority. And arraying students to form mixed-income schools is hard in North Carolina, where more than half the students qualify for free and reduced-price lunches (a proxy for determining students of low-income circumstances), and especially difficult in distressed rural counties with even higher proportions of students in poverty.

Another important way to improve the poverty-fighting potency of public education is for North Carolina to regain momentum in expanding high-quality early childhood education. Kirsten Kainz, a former Durham school board member and now director of statistics at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, recently pointed me to a paper, with 10 co-authors, summarizing research on preschool education. Let me summarize the summary with two illuminating quotes, the second of which responds to concerns that educational gains in early childhood “wear off’’ as students proceed through elementary, middle, and high school.

“Quality preschool education can benefit middle-income children as well as disadvantaged children; typically developing children as well as children with special needs, and dual language learners as well as native speakers.”

“Long-term benefits occur despite convergence of test scores. As children from low-income families in preschool evaluation studies are followed into elementary school, the differences between those who received preschool, and those who did not, on tests of academic achievement are reduced. However, evidence from long-term evaluations of both small-scale, intensive interventions and Head Start suggest that there are long-term effects on important societal outcomes, such as high-school graduation, years of education completed, earnings and reduced crime and teen pregnancy, even after test-score effects decline to zero.”

For a while, North Carolina appeared to position itself as a national leader in early childhood education initiatives. Gov. Jim Hunt had launched SmartStart, a state-local program of child care, as well as health and family support services. Subsequently, Gov. Mike Easley launched More at Four, an in-school four-year-old kindergarten for economically at-risk young people.

When they gained a majority, Republican legislators had questions about whether SmartStart and More at Four overlapped. The legislature converted More at Four into North Carolina PreK, and placed it in the Department of Health and Human Services, not in the Department of Public Instruction that oversees schools.

Thus, the state retains platforms for strengthening early childhood education and offering it to more of the state’s ethnically diverse population younger than 5 years old.

The question now is whether North Carolina has the will to strive to break the inter-generational cycle of poverty by enhancing the life prospects of children who live in poverty through no choice of their own.

Here is EdNC’s additional research on schools as places where young people can eat, and where they should encounter healthy food.