Last week I had the opportunity to visit UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus and speak to a class full of social entrepreneurs as part of UNC’s Food for All campus-wide challenge.

I graduated from UNC in 2008, and yet it still strikes me as entertaining to speak before students. As I told them last week, it seems like just yesterday that I was also wearing basketball shorts, playing on my iPhone, and generally thinking about my next meal during a lecture.

The three hundred-plus students who assembled for ECON 145 last week are likely far smarter than I was during my time on campus.

I was asked to speak as part of a panel designed to present “reverse pitches” to the students — in other words, we were asked to present challenges in hopes that we would inspire the students to present possible solutions. The energy and optimism in the room was palpable.

Tamara Baker from No Kid Hungry NC, Maureen Berner from the UNC School of Government, Cynthia Ervin from the Department of Public Instruction, and Jim Green from Stop Hunger Now were the other panelists.

The numbers that we presented were staggering.

Twenty-seven percent of North Carolina children are food insecure.

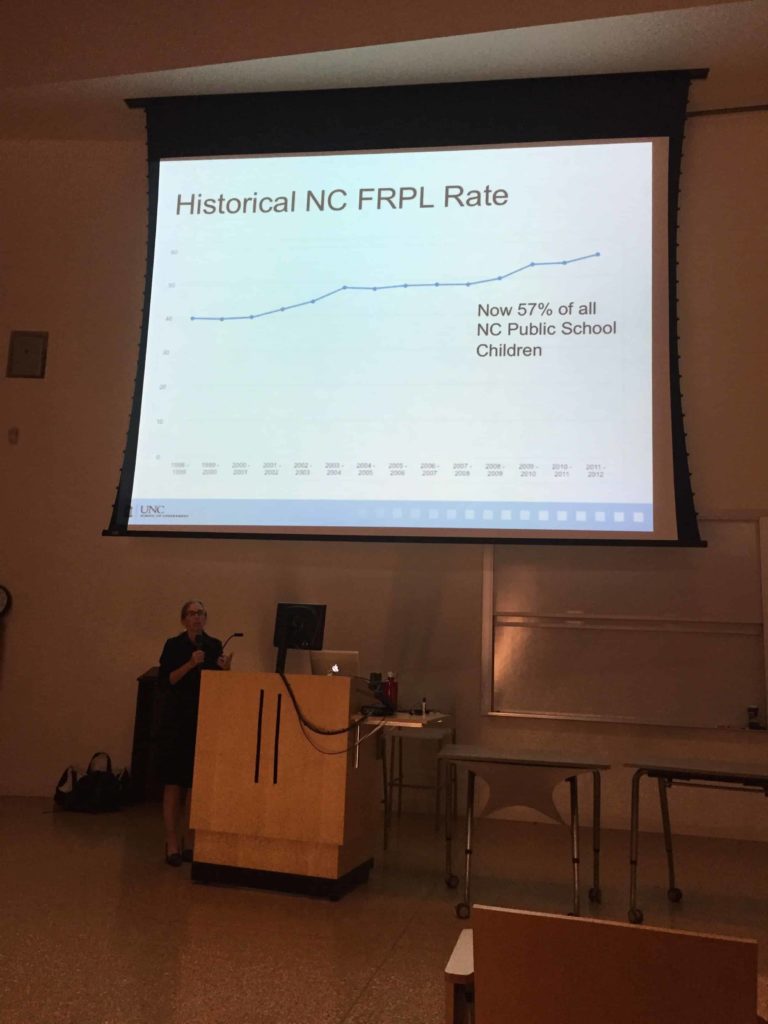

Nearly 60 percent of North Carolina children enrolled in our public schools qualify for free or reduced price lunch. Sixty percent.

The Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina distributed 55 million pounds of food in 2014, as opposed to five million pounds in 1991, and the need is only growing.

When our panel finished presenting the challenges, one of the UNC professors asked the assembled students if they had known those facts before the day began. Just two dozen hands of the 300+ students went up.

I left the class following the lecture, ducking and dodging students on their way to class, and walked through the campus for a while to think. It was one of those gorgeous days where summer bleeds into fall and you can feel a hint of the crisp weather to come. I walked around the bell tower, strolled through the quad, and stopped to think in the Paul and Sheila Wellstone memorial pocket garden.

That evening I resumed reading $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America by Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer. Their book zeroes in on the fact that by “early 2011, about 1.46 million American households, with 2.8 million children, were living on less than $2 in cash per person per day in a given month.”

$2 per person per day is a measure of extreme poverty that the World Bank uses for global poverty.

As I read the book, I found myself stunned by the statistics and the story that was being told. I was particularly surprised that these facts were new to me given that I have dedicated much of my life to examining and working on these issues.

Yet extreme poverty, just like hunger, is often invisible to us. We commute to work, to places of faith, to restaurants and coffee shops. We go on runs through our neighborhoods or on greenways. We pay our bills, raise our children, and tend to our pets. How often do we come face to face with poverty? How often do we open our eyes to the problems of others?

The next morning I woke up and went on a run. In the months after I lost my wife I found that running was both an excellent form of therapy, but also a time to think.

I often run through Southeast Raleigh, past the Camden Street Learning Garden that the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle manages in an attempt to pilot strategies to combat the food desert, and on that morning I thought of both the hunger pitch and $2 a day.

We are bombarded by statistics, flooded with content, and busy keeping up with our own lives. Was it really surprising that so few students knew about the hunger crisis in North Carolina? Should I have really been shocked by the prevalence of extreme poverty in the United States?

Should I be surprised by how often people are invisible? Unseen?

Former President Bill Clinton gave a commencement address at Harvard University in 2007 where he told the students:

“In the central highlands in Africa where I work, when people meet each other walking…on the trails, and one person says, ‘Hello, how are you, good morning,’ the answer is not, ‘I’m fine, how are you?’ The answer translated into English is this: ‘I see you.’

“Think of that. ‘I see you.’

“How many people do all of us pass every day that we never see? You know, [after] we all haul out of here, somebody’s going to come in here and fold up 20-something thousand chairs. And clean off whatever mess we leave here. And get ready for tomorrow and then after tomorrow, someone will have to fix that. Many of those people feel that no one ever sees them.”

It struck me as I ran through Raleigh that perhaps the students reaction was cause for optimism rather than pessimism. After all, the students were resolving to make a difference in the lives of others through responding to the challenge, and they had attended a class to see the challenges facing our state.

The challenge for all of us is to keep raising up this issue that faces our state, and to show that solutions do exist to our most pressing challenges.

The challenge is to make it clear that this is not a Republican or Democratic issue. Families of each political party, or no political affiliation at all, live in poverty. My own family was poor, occasionally hungry, and conservative.

The challenge is for us to make sure that all of our children are no longer invisible, so that we might say to all of the children of North Carolina:

We see you.