Editor’s note: This article is part of EdNC’s playbook on Hurricane Helene. Other articles in the playbook are available here.

Including a resource from a meteorologist on assessing weather and risk

Kristin Buchanan, student services coordinator at Yancey County Schools (YCS), has grown up in the shadow of Mount Mitchell. And it casts a large one. It’s not only the highest peak in North Carolina, but the tallest mountain in the Appalachians, reaching 6,684 feet above sea level.

Mount Mitchell is well over a mile high and nowhere near the sea. I’m taking special care to note this, because this playbook is about a hurricane, and the stories of hurricanes begin in the ocean.

In the southeastern United States, we have a season dedicated to the hurricane. From June 1 to Nov. 30, when a storm is approaching the coast, those close to the Atlantic or Gulf are tuned into the weather and possible hurricane landfalls. While a handful of named storms have had impacts in the western North Carolina (WNC) area over the last century, it is historically not typical for someone in the Appalachian region, like Buchanan, to be worried about a hurricane.

Well over 400 miles from the North Carolina shore rises Mount Mitchell and the home of Buchanan. She attended YCS, as have her children, and has spent the last 24 years working for the school district.

She and her neighbors on NC-80 aren’t strangers to storms. She remembers a big blizzard as a middle schooler in the winter of 1993 when the snow was so high it reached the windows of her dad’s pickup truck. And right before she got married in 2004, the South Toe River, which runs along NC-80, flooded due to impacts of Hurricane Frances. She says water reached her house.

So yes, there have been storms, but none so significant that it could aptly prepare her region for the end of September 2024 and Hurricane Helene.

“We’ve had some flooding,” Buchanan recalls, “but nothing — nothing, nothing, nothing — you know, like Helene.”

“Mount Mitchell acts as a sponge,” says Buchanan. “I mean, it just keeps squeezing rain out, squeezing rain out where it may not be raining that hard other places, [but here] it will continue to squeeze and squeeze and squeeze like a sponge — all the rain out.” Her whole life, she says, it’s been hard for anyone to predict the weather in her particular area.

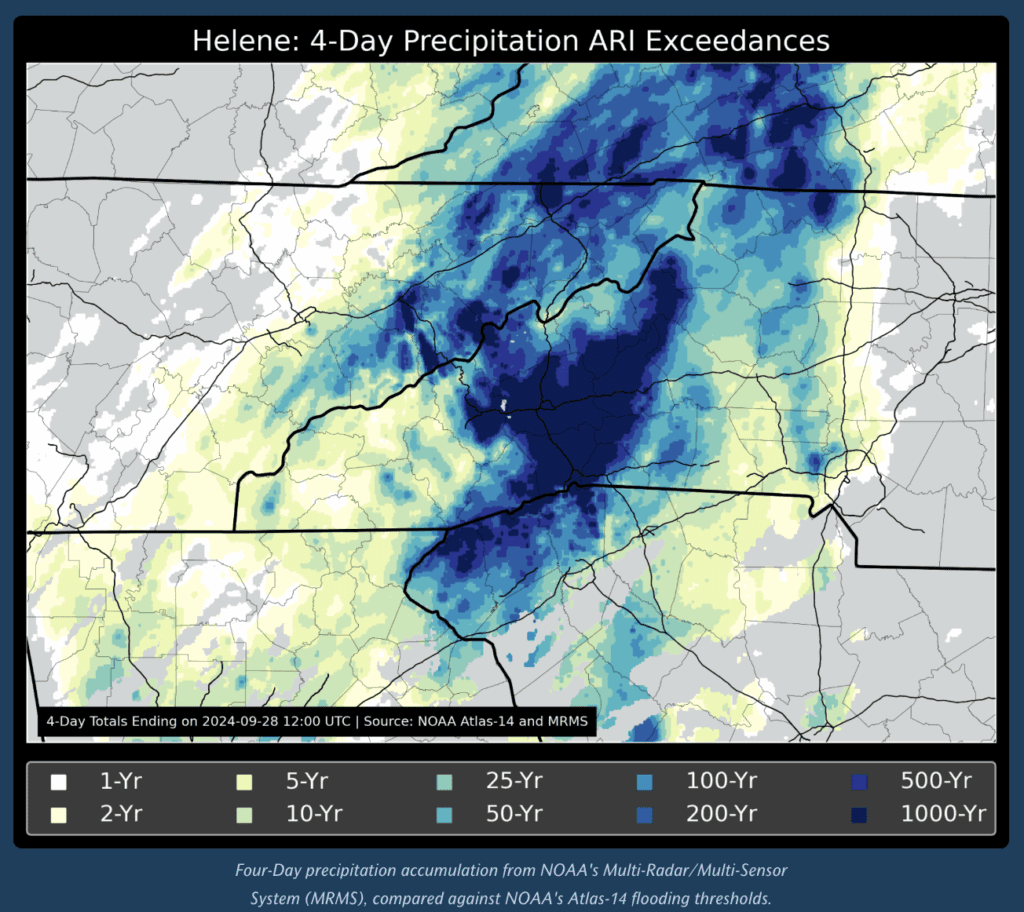

She lives a five minute drive from the township of Busick. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Busick had the highest observed rainfall of any place during Hurricane Helene. A recorded 30.78 inches of rain fell from Sept. 25-28, 2024.

Buchanan’s colleague at YCS, Tina Haney, lives a couple miles down the road from her and South Toe Elementary, where she works in cafeteria management. Haney has a weather station at her house. It measures rainfall, barometric pressure, and wind speed, among other things. She said from Monday, Sept. 23 to Friday, Sept. 27, she recorded 48 inches of rain.

John Wilson is the resident fire chief at Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College (AB-Tech). He lives in Black Mountain, well over an hour’s drive from Busick, and he is in his 40th year of service at his local fire department in Black Mountain.

He said, “You look at the river, you always hear (that) water always follows a path of least resistance. However, in this situation, it was following the path of least resistance, but it was also making its own pathway as well.”

Traveling to the impacted areas to cover the aftermath of Helene for EdNC, I heard this rhetorical question over and over again — “Who has ever heard of a hurricane in the mountains?”

At a church in Old Fort on Oct. 8, Principal Jill Ward posed this same question to her students’ families as they sat in pews learning what would become of their recently flooded school building.

Old Fort Elementary School in McDowell County is 40 miles from Busick.

Mill Creek, which flows behind the school, swelled and brought in water and sediment into the building, displacing students for a year. The school’s three buses were destroyed — one found miles away in a field.

Ashe County is 80 miles north of McDowell, and that school district was out of school for 33 days due to damaged roadways.

While each of these counties is in WNC, their populations are not consolidated. Mountains, valleys, ridgeways, and forests naturally divide the region and communities.

The effects of this storm were incredibly widespread. Two days after the rain stopped, 25 of North Carolina’s 100 counties were declared federal disaster areas.

Why did this much rain fall, where did it fall, and what were the consequences for our schools, our community colleges, and the region? Most importantly, what did people do in the face of the flooding? What does rebuilding and recovery look like, and how do we prepare for the future?

We hope our playbook helps people prepare and, if needed, put things back together after the next storm.

Setting the stage: Climate, conditions, and community in WNC

A hurricane and the mountains

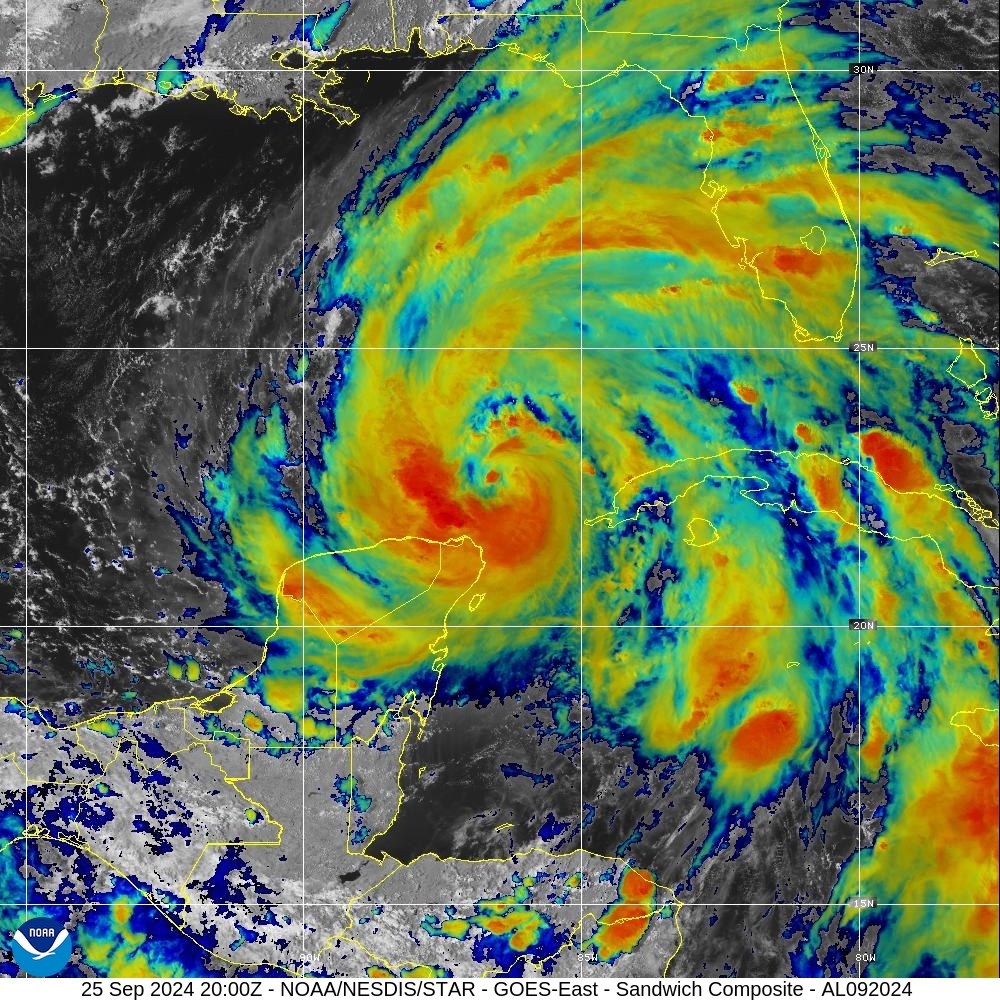

At first, a hurricane is just a storm — a storm in the ocean that builds upon itself with ingredients of warmth, wind, and moisture. Warm ocean air rises into the established storm, creating low pressure underneath the developing cyclone of clouds. That low pressure allows more air to rush in — where it then rises, cools, and forms into more clouds. Once wind speeds in this swirl hit 74 miles per hour, it officially becomes a hurricane.

Before Hurricane Helene came to WNC, Southern Appalachia had what they call a predecessor rain event (PRE).

According to NOAA, “conditions in the upper atmosphere funnel enhanced water vapor from the Gulf waters towards the Southeast U.S.” The incoming hurricane moved a front into the mountains. Then, “the interaction of this moisture with the terrain of the Blue Ridge Mountains resulted in nearly six to eight inches of rainfall before Helene arrived in the area.”

With the PRE, waterways were already swollen and the ground highly saturated. Then Helene arrived in the mountains and created an oprographic uplift. This is when air is forced upwards due to mountainous terrain, and the air can cool, condense, and turn into clouds. Because Helene was an already intense system, the clouds produced extensive precipitation.

The average rainfall for September in the region is usually five to six inches, according to data from NCEI’s 1991-2020 normals. In “Helene in Southern Appalachia, One year later: An event analysis and how we move forward,” NOAA estimates five and a half months’ worth of rainfall fell in just four days.

The rurality of WNC: Roads and water

Western North Carolina is rural, as are most of the counties in the state. Of the original 25 declared federal disaster areas, 20 are considered rural by the NC Rural Center.

More sparsely populated, these counties have long winding roads due to mountainous terrain, protected national forests, and natural waterways. Neighbors may not be next door, but miles down the road. School buses travel down through hollers and across one-lane bridges to pick up students around these areas.

There were 2,000 recorded landslides during Helene. These landslides took down mountainsides, trees, homes, and cars, displacing the landscape and creating heaps upon heaps of debris.

According to the US Army Corps of Engineers, between Sept. 27, 2024 and Dec. 11, 2025, they removed 9,049,119 cubic yards of debris from 22 counties.

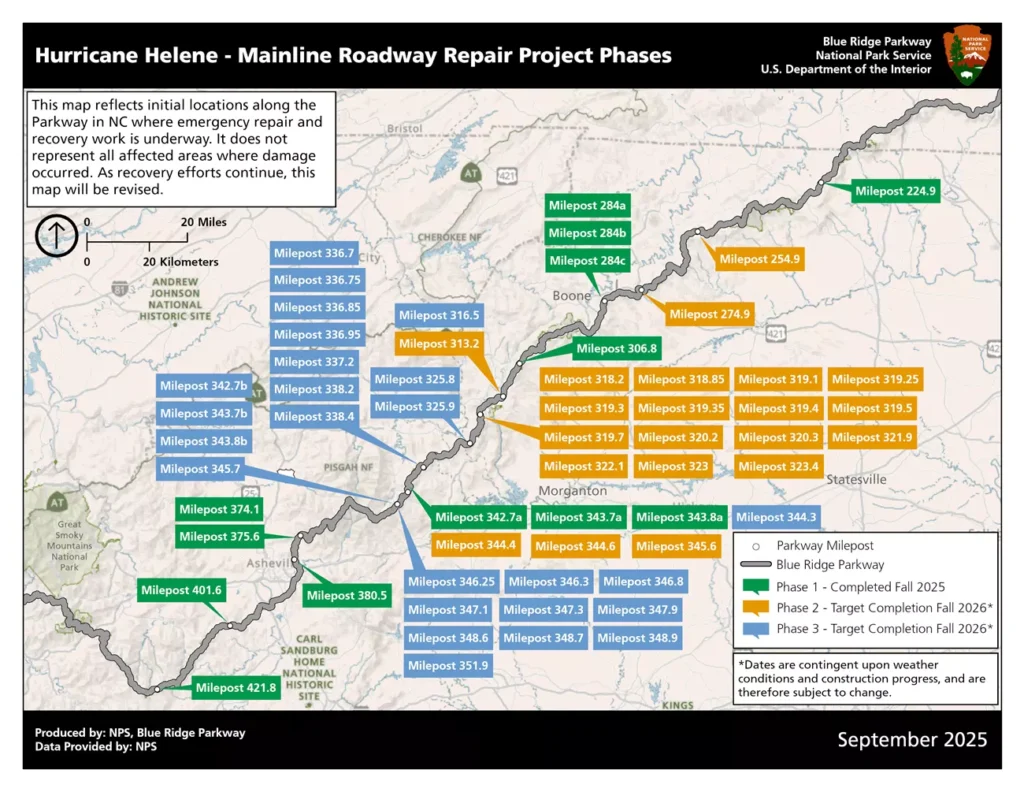

The North Carolina Department of Transportation recorded over 9,000 damage sites and more than 1,400 road closures after the storm. The Blue Ridge Parkway runs through WNC, and the National Parks Service identified 57 landslides that impacted 200 miles of the historic landmark byway.

The region’s infrastructure — electricity, roads, water, and communication — was destroyed. In Mitchell County, Spruce Pine’s water treatment plant flooded, cutting off water for thousands of customers. Asheville was without drinkable water for more than 50 days.

According to the Hurricane Helene Damage and Needs Assessment from the Office of State Budget and Management, there were at one point 900,000 homes and businesses without electricity due to the storm.

The report states, “the breadth of the storm caused enough damage that eleven K-12 school districts closed for 10 or more days, and 82 public schools across six local education agencies (LEAs), two community colleges, and one UNC institution closed for 20 or more days.”

The report estimates the total cost in damage and needs as $59.6 billion.

The challenges after Helene were staggering

First responders compared their experience of Helene to other natural disasters they had encountered, noting the challenges were staggering. “Just so people maybe can understand that Helene for me, that’s the worst storm I’ve ever seen, far as in our area, and just worst storm in general, just devastation,” said one lineman.

The state’s response to the storm was complicated by a gubernatorial transition. Gov. Roy Cooper had just three months left in office when the Helene hit.

Gov. Josh Stein took office on Jan. 1, 2025, and immediately established disaster response as a priority, establishing the Governor’s Recovery Office for Western North Carolina (GROW NC) on Jan. 2nd. According to the website, the goals include:

- Developing strategies and goals to guide and accelerate recovery efforts

- Facilitating collaboration across state agencies supporting recovery

- Deploying the expertise and innovation necessary for a swift and robust recovery effort

- Coordinating communications about recovery-related needs across state and local governments

- Ensuring transparency and accountability, including offering regular updates to the public and meeting federal and state reporting requirements

- Providing administrative assistance to the Governor’s Advisory Committee on Western North Carolina Recovery

The website includes a recovery resource hub — where those impacted can scroll through organizations offering help, ways to get connected to a NC disaster case manager (someone who can guide you through recovery process), and a list of upcoming program and grant deadlines.

Find members of the GROW NC leadership here. For recovery priorities and progress and to find ways to stay connected, see here.

Also staggering was the human spirit and the sentiments of gratitude, blessings, and resilience.

“You just don’t know what the day is going to bring, you know?” said Kathy Amos, superintendent of YCS. Her district was the last in the state to return to school. “We are able to see our students, and we’re so blessed to have them back in the building.”

A meteorologist helps us understand how to assess the weather and risk moving forward

by Tom Sorrells

In the world of instant communication, websites, notifications, and social media, getting accurate, correct, and true weather information can be difficult. It can sometimes become a battle over headlines that are designed for attention and clicks, versus good information that applies to you.

When trying to determine what risk you are facing and what to do next, it is important to know if you are under a watch or warning. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) will issue a hurricane watch when an area MIGHT experience hurricane-force winds within 48 hours. That hurricane watch will become a hurricane warning if the NHC determines the area WILL have hurricane-force winds within 36 hours.

The best place to keep up with this change is on the NHC website. This page will update every six hours at 5 a.m., 11 a.m., 5 p.m., and 11 p.m.

Now let’s talk about inland threats. The National Weather Service (NWS) will be our guide for all things “local.” North Carolina is served by seven different branches of the NWS. The branch that serves you will be based on what part of the state you live. For Asheville, the NWS office is the Greenville-Spartanburg office. The Wilmington office covers the southeastern coast, and the Newport/Morehead City office covers the northeastern coast all the way to the Virginia state line.

Here are the links to all the offices:

- NWS Blacksburg, VA

- NWS Greenville-Spartanburg, SC

- NWS Morristown, TN

- NWS Newport/Morehead City, NC

- NWS Raleigh, NC

- NWS Wakefield, VA

- NWS Wilmington, NC

To determine which NWS office serves your area, navigate here and type your city or zip code in the search bar in the upper left corner. Hit “go,” and on the page that loads, there will be a section in the upper left corner that says “Your local forecast office is,” followed by one of the NWS offices. Click on that NWS office’s link, and bookmark it for easy access.

You will be looking for Hurricane Local Statements (HLS) and Tropical Cyclone Watch/Warning (TCV). These will include tropical storm watch/warnings, hurricane watch/warnings, high wind advisories, tornado watch/warnings, and flood watch/warnings. In addition, you will also be on the lookout for Special Weather Statements.

I can not stress enough that all information about what will happen in your backyard will come from the local NWS office. The NHC will focus more on hurricane track and coastal impacts. The NWS will focus on your local impacts.

When it comes to plans, I believe you should always be ready. What does “ready” look like? It means knowing who is making the decisions and where to get the right information (see above), being on stand-by when the “watch” is issued, and moving as fast as possible when the “warning” is issued.

The time frame of 36 hours should be enough for you to make the right decisions. If you feel rushed by that time frame, it might serve your interest better to make moves when the “watch” is issued at the 48-hour mark. I strongly advise you not to wait any later than the 36-hour mark.

When deciding who to listen to online and on TV, make sure the person you are watching/reading has the Certified Broadcast Meteorologist (CBM) Seal of Approval from the American Meteorological Society.

EdNC’s playbook

When the Pactiv Evergreen mill closed in Canton, EdNC used a playbook from the Pillowtex closing as our roadmap. The lessons learned from the insurance subsidies provided for workers after Pillowtex closed were especially important, and may have saved lives in Canton by reducing the suicide risk. We realize that the authors of the Pillowtex case study could not have predicted at the time how important their work would be.

It is in that spirit that we will be rolling out this playbook during early 2026. Here are the forthcoming chapters:

- ‘Mutual aid’ in the days and months after Hurricane Helene, by Ben Humphries

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: Lessons learned in emergency management, by Ben Humphries

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: Lessons learned in early childhood, by Liz Bell

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: Lessons learned from community colleges, by Emily Thomas

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: The role of philanthropy in disaster relief and recovery, by Kelley O’Brien

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: Lessons learned in leadership, trauma, wellness, and ‘facing forward’, by Mebane Rash

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: The role of faith and faith institutions, by Hannah Vinueza McClellan

- EdNC’s Hurricane Helene Playbook: Lessons learned in K-12, by Mebane Rash and Caroline Parker

Recommended reading