The Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission (PEPSC) met Thursday for its monthly meeting and discussed a wide range of issues, including a newly-recognized accrediting organization for educator preparation programs, responses to passage of Senate Bill 621 regarding teacher licensure requirements, and further movement on an evaluation system for educator preparation programs that could now be subject to sanctions under House Bill 107.

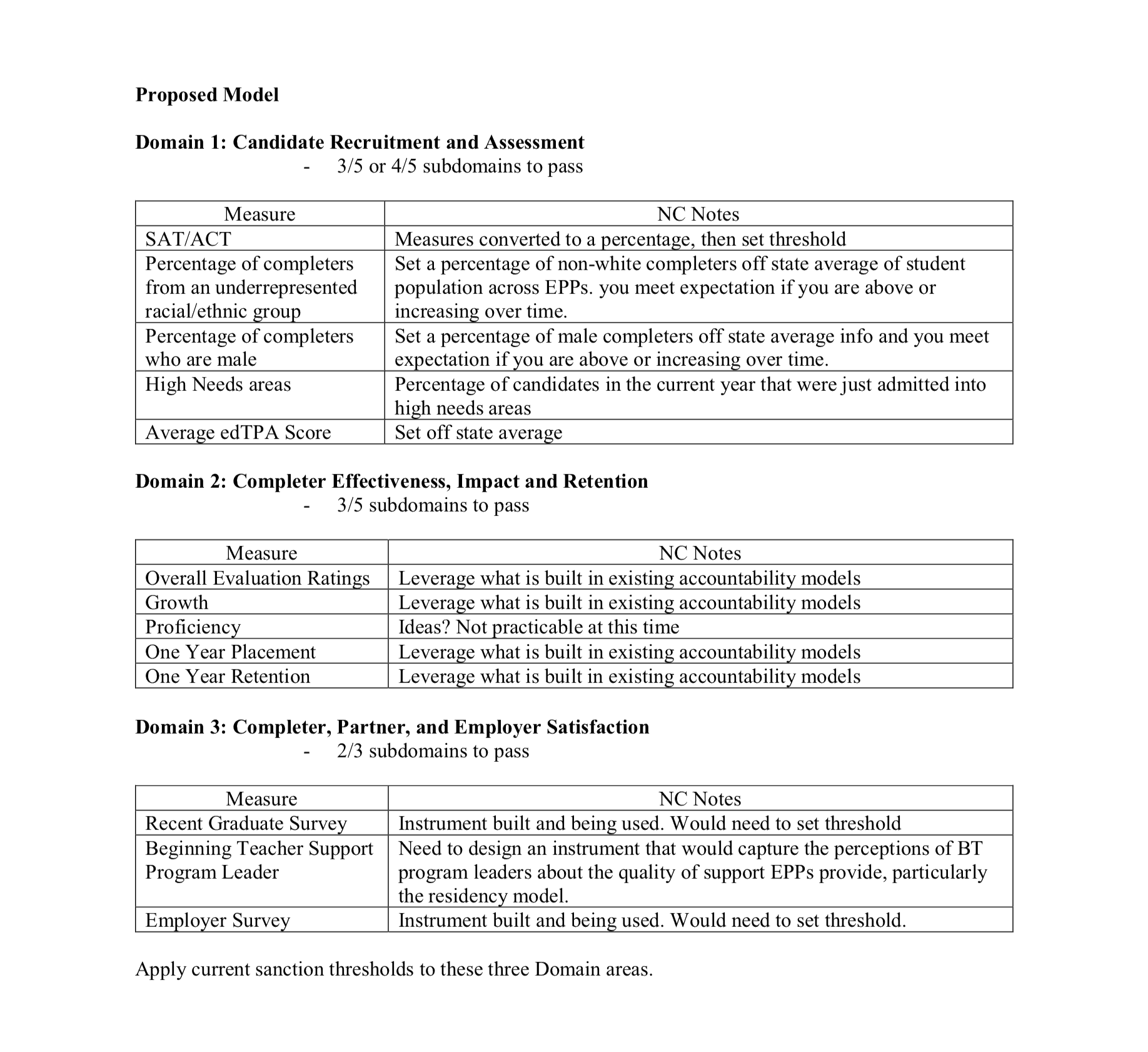

A highlight from the meeting was ground gained on a starting point for developing accountability standards for educator preparation programs (EPPs). The assessment and performance subcommittee of the commission met to further discuss design of an accountability model for EPPs to comply with House Bill 107, which was signed into law by Gov. Roy Cooper in July.

First, some context…

When PEPSC was created in 2017, the same law which created it also established sanctions that EPPs should face if their scores for certain performance measures fell short. Initial fear that an EPP could face sanctions for falling short on any one performance measure were quelled in July when House Bill 107 was passed. EdNC.org wrote about impact of the bill last month.

The first thing House Bill 107 did was lay out three criteria for judging performance of EPPs.

- Performance-based on the standards and criteria for annual evaluations of licensed employees (NCEES).

- Proficiency and growth of students taught by educators holding an initial professional license, to the extent practical (EVAAS).

- Results from an educator satisfaction survey, developed by the State Board of Education with stakeholder input, performed at the end of the educator’s first year of teaching after receiving an initial professional license.

References to initial professional license were expanded to also apply to recipients of residency licenses (which are awarded to teachers who move here from out-of-state and sets them on track for North Carolina licensure).

The second thing House Bill 107 did was allow the State Board to come up with “a formulaic, performance-based weighted model for the purposes of comparing the annual report card information between each educator preparation program.”

This could allow the state to make sure some criteria carries more weight than others when evaluating EPPs.

As EdNC.org reported previously, the law as written essentially said that if EPPs fail on any one of the required accountability standards, they would be sanctioned. If EPPs repeatedly fail, this could lead to probation and eventually revocation of state authorization for the EPPs to produce teachers. After passage of House Bill 107, the subcommittee went to work designing a weighted formula that would soften the previous, all-or-nothing approach.

What happened at the meeting?

The subcommittee agreed on a starting point for developing the weighted model and set a timeline for completing the work. The deadline to provide the joint legislative action committee with a proposal approved by the state board is Feb. 15. In order to comply with that deadline, the subcommittee took feedback from previous surveys of the subcommittee and determined a starting point for discussions, with the goal of taking recommendations to the entire commission in December, presenting the proposal to the State Board in January as a topic of consideration, and setting it for a vote of the State Board in early February.

The starting point was derived from an accountability model utilized by Tennessee, but takes five “domains” of accountability and conflates it into three to specifically address the three state-mandated performance measures.

The idea was to “take a look directly at the Tennessee accountability model and [ask] are there things in the accountability model from Tennessee that we can glean from rather than reinventing the wheel,” said Andrew Sioberg, director of educator preparation for DPI. “We can take spokes from this wheel, and they may be useful to us as we create our own performance accountability model, the weighted model.”

Initial feedback on what spokes may be useful came from the subcommittee prior to Thursday’s meeting and boiled down to three areas of concern. The subcommittee wanted to be careful in promoting diversity among EPP students without penalizing EPPs that have historically had low numbers of diverse applicants and a low number of diverse residents living in their area.

The subcommittee also cautioned that the accountability model should not unintentionally incentivize EPPs to narrow a subgroup in order to comply with performance standards. For instance, if an EPP has few white, male students, and that subgroup is underperforming, the accountability standards should incentivize EPPs to help raise that subgroup rather than stop recruiting them in an effort to avoid low numbers among the subgroup.

Finally, since the EPPs will be measured based on its students performance as teachers after graduation, the subcommittee voiced caution over unintentionally discouraging graduates from taking positions in challenging, historically underperforming districts. This is of particular concern as the starting-point model proposal would also hold EPPs accountable for placing student teachers in low-performing districts.

The subcommittee seemed universally pleased with the idea of three domains, with sub-domains within each that would result in a total score for that domain. This would allow EPPs, they said, to focus on things they do well without the fear of sanctions if they fell short in any one area. Concerns mainly centered around the prospect of EPPs receiving sanctions.

For instance, subcommittee member Ann Bullock, dean of the School of Education at Elon University, said her school has a diversity recruitment plan. However, “we only get what comes to us, we can try all we want,” she said. She wondered if recruitment plans and evidence of attempting to diversify would be the accountability standard — like setting a percentage goal for increasing diversity and showing all of the efforts taken to achieve the goal.

“At the end of five years, you could have tried 100 different things and none of them worked,” she said, “But you tried 100 different things.”

Evidence of the attempts, she said, should be considered somewhere because some schools just may have difficulty increasing their diversity.

Andrew Lakis, executive director of Teach For America — Eastern North Carolina, suggested using a three-tiered measure of compliance with recruitment, including (1) growth over time; (2) how the education school performs relative to the larger university it sits within; and (3) setting a state target for percentage of diverse students.

Van Dempsey, dean of the Watson College of Education at UNC-Wilmington, pointed out that his college of education does not have a direct impact on recruitment of freshmen. The university at large recruits freshmen, and that creates the cohort group from which the undergraduate college can pull. Even graduate programs at the college of education, while they might prioritize diversity, have other priorities that are competing for consideration in recruiting strong teacher candidates.

“So part of this is nuanced,” he said. “While we don’t want to make it overly complicated, we don’t want an accountability model that misses the point.”

He said the model should not conflate attributes of an EPP and attributes of a strong candidate. With respect to the latter, he said: “Can the person teach? That’s the most important question.”

Dempsey worries that having a diverse EPP that is not producing quality teachers defeats the purpose of the commission, as would an accountability model that sanctions an EPP that produced high-quality teachers but is not diverse.

Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, attended both the commission’s meeting and the subcommittee meeting. He spoke at the end, encouraging the subcommittee to continue its hard work but to try not to develop a model out of fear of sanctions.

“If we don’t put requirements, nothing’s going to happen,” he said of the legislative sanctions. “You can say it will, but history shows pretty clearly, we’re all so busy doing what we do. But don’t let fear of failure be a deterrent.”

Recommended reading