Share this story

- There's a lot of reading research out there. How will teachers know what to follow, and what do they need to implement effective instruction?

- “I think that's the next important step. We have the science of reading. But what does that mean? And what are we going to do with it? How do we pull all these parts together and see the outcome?”

|

|

A school district leader observes a second-grade reading teacher leading students through the end of a phonics lesson. It’s refreshing, she says, watching teachers take what they learn in training and use it in their classrooms.

“This is what we want to see for our students — to make sure we’re reaching all of them, not just some of them,” the district leader says.

Just then, a student moves toward a row of boxes atop a bookshelf in the back of the room. Inside are leveled readers — books designed to help students predict words on pages. They aren’t designed to help students practice phonics skills, like taking apart and blending sounds in words.

These books are vestiges of an approach the state is discarding as it implements a law that grounds instruction in the science of reading. But nobody has discarded these books, the district leader notices. She winces as the student tips the box slightly forward and pulls out a book.

“There’s a lot of great changes happening,” she says, “but it’s not all going to happen at once.”

Behind the Story

This article is part of a series updating North Carolina’s efforts around the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021. EdNC visited 10 schools across five districts and interviewed leaders from the Department of Public Instruction, UNC System, and North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities. We wanted to learn about changes to instruction, the state of curriculum and instructional materials, the role of building student background knowledge, challenges from teacher turnover and chronic absenteeism, and where teacher prep programs are with implementation. You can find the entire series here.

The state’s definition of science of reading covers a lot of ground. So does the reading research. Fidelity to both means that many things in the classroom need to align. And teachers can’t be the only ones trying to pull it all together.

For example, as phonics instruction changes, students will still need districts and schools to provide decodable books so they can practice what they just learned.

But it’ll take time for everything to fall into place.

“I think that’s the next important step,” said Amy Powchak, an early intervention instructional coach in Asheville City Schools. “We have the science of reading. But what does that mean? And what are we going to do with it? How do we pull all these parts together and see the outcome?”

Critically examining materials, beyond their marketing claims

As educators navigate that process, they confront decisions about what materials to use. And how to use them. History teaches that relying on materials that market themselves as aligned to the science of reading might not work.

The term “science of reading” is easy to use – not unlike the term “balanced literacy.” While certain approaches that vendors label as balanced literacy are now under scrutiny, that wasn’t always the case. The balanced literacy approach, “in its infancy, had a focus on skills-based teaching and explicit instruction during independent blocks of reading,” one graduate paper says.

But in the 2000s, publishers started selling curricula labeled as “balanced literacy” that didn’t fit that graduate paper’s definition. The curricula popularized certain approaches — like using context clues and cues to guess at words. Rather than emphasizing explicit instruction, these “balanced literacy”-labeled approaches looked more like whole language, a literacy theory that says kids will learn to read naturally through exposure to books.

“It’s not going to take long for these vendors to slap the words ‘science of reading’ on the front of materials,” said Lynn Plummer, Stanly County Schools’ director of elementary education. “But will it actually align with the research?”

Determining what aligns with the “research” is a puzzle itself.

The state is investing in teachers to become experts on evidence-based reading instruction. The hope is that teachers become confident choosing different instructional materials, knowing which to use for different purposes, when to use them, and how to tie it all together.

“But that comes down to the implementation science – how are we supporting the rollout on a continual basis, because this is a lot of information that teachers are getting all at once,” Powchak said.

What does instruction grounded in the ‘science of reading’ really mean?

The research is extensive and fluid, and often tells what doesn’t work rather than what does. Educators need to critically examine a studies’ claims before deciding to follow any of its recommendations or findings.

Tim Shanahan, a researcher, author, and professor emeritus, writes that “evidence must be derived from a scientific method that is appropriate to the claim being made. If you want to claim that a particular instructional method or approach improves reading achievement, you need to prove that; that such instruction is more beneficial than other approaches.”

That means trying that approach out in a classroom and comparing its results to results yielding from other approaches. But not all research is conducted in classroom settings. And some that is done in classrooms uses relatively small sample sizes. Other researchers work in labs, often with even smaller samples.

It’s a lot to expect educators to sift through the research, figure out which studies are actually designed to predict movement in student outcomes, and turn all that into classroom practices designed to teach a lot of things. A lot of things.

The expectation isn’t for teachers to figure out things that researchers are still testing. Over time, through different practices, the hope is that teachers will get comfortable with what works for their students.

But, for now, the focus in North Carolina seems to be on something else. The research makes clear that reading instruction should be explicit and direct, and it should cover things like decoding, oral language, and writing. For years, that idea has been missing from what some teachers are taught. It’s been missing, also, from the curriculum many teachers used to teach students. Getting that fixed is where this all starts.

“Right now, this is really the first step in moving [away] from balanced literacy,” said Theresa Melenas, executive director of instructional services in Clinton City Schools.

Finding a groove piecing reading programs together

As teacher training in Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) unfolds, it’s leading to a lot of changes in classrooms. LETRS covers mostly decoding research and instruction in the first year, and oral language and background knowledge in the second.

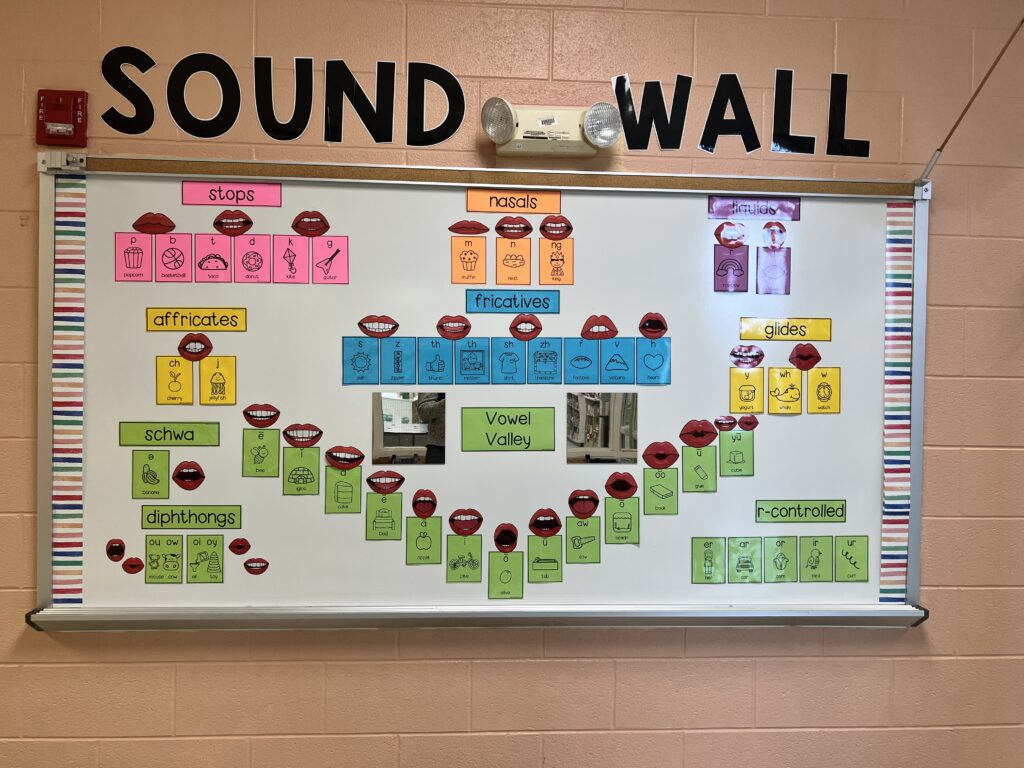

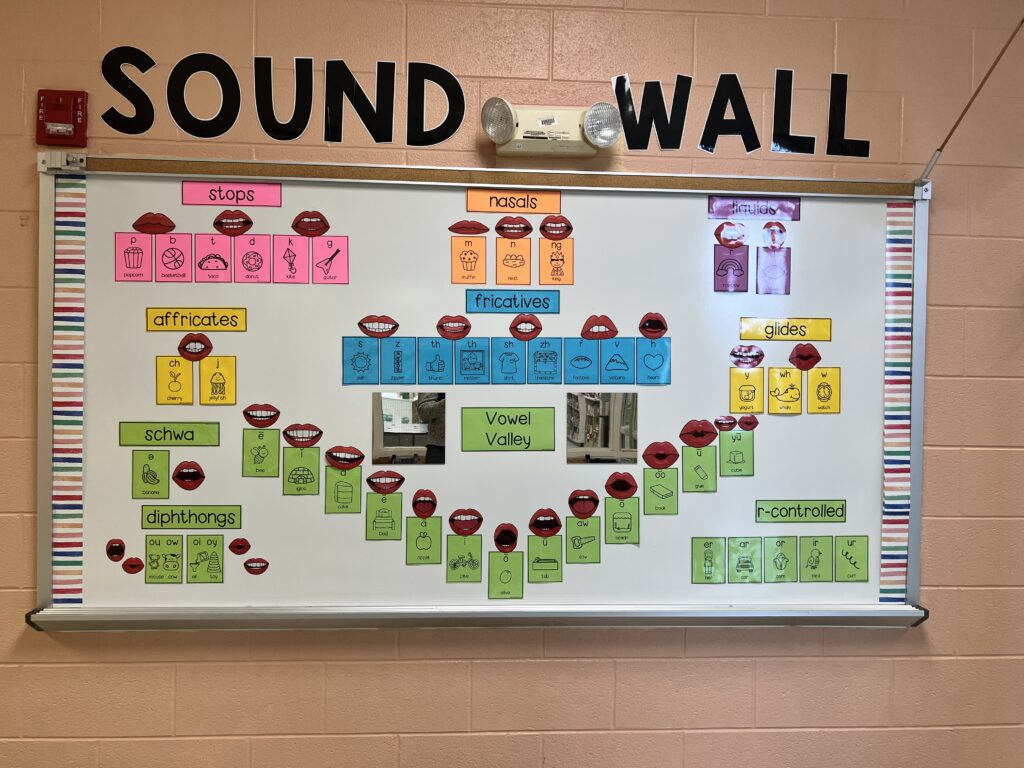

For decoding, LETRS emphasizes the development of phoneme awareness. Phonemes are the smallest unit of sounds in a word LETRS takes a print-to-speech approach, meaning students are connecting written letters to those units of sound.

A lot of districts, upon examining assessment data, determined that they weren’t teaching phonemic awareness skills effectively. So districts invested in programs that supplement core curriculum and focus on phonemes.

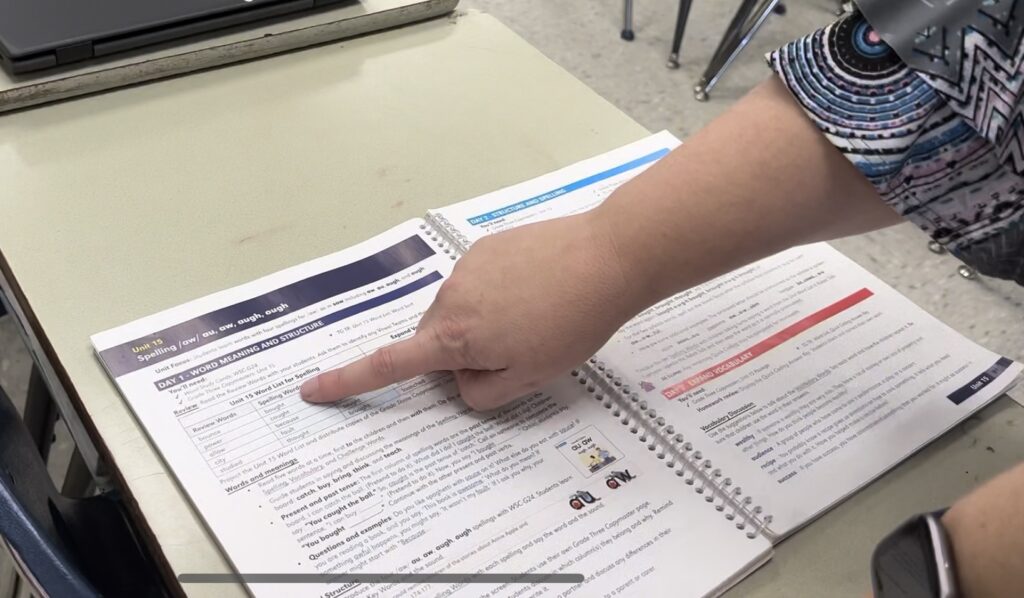

Early on, district and school leaders noticed teachers following these programs page-by-page from the teacher guides. Teachers then moved on to a different program for phonics instruction. Finally, teachers used core curriculum to support knowledge building and comprehension.

Sometimes, that could look like three completely different lessons throughout a single day’s literacy block. And when the lessons don’t connect, some of the programs’ activities become ineffective.

For example, some phonemic awareness programs have students practice phonemes out loud, without seeing the printed letters in front of them. The research does not clearly support that.

Now, educators are finding ways to connect lessons throughout the various programs and curricula. That means phonemes that students hear and repeat during phonemic warmup exercises are presented to students again, in print, through follow-up phonemic awareness lessons or through the phonics lesson.

A walk down the halls of Perquimans Central Elementary shows this in action. Principal Tracy Gregory stops outside a classroom doing a Heggerty phonemic warmup activity.

“That’s just introducing phonemes,” she says. “It’s getting students used to the idea that sounds are represented by letters.”

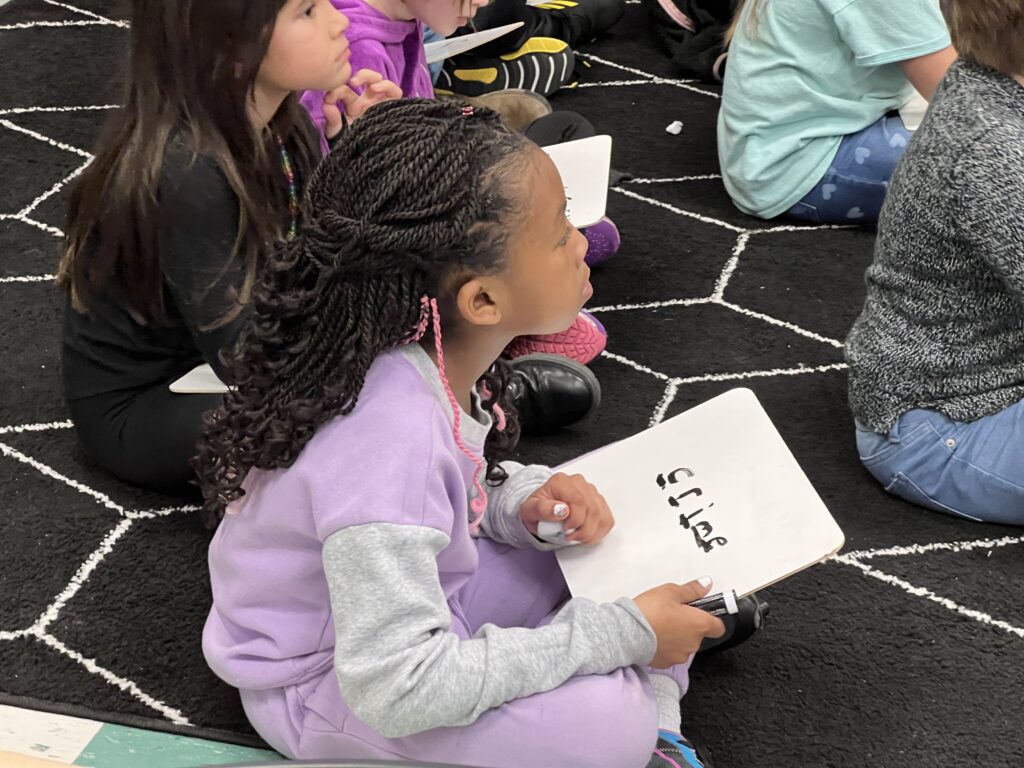

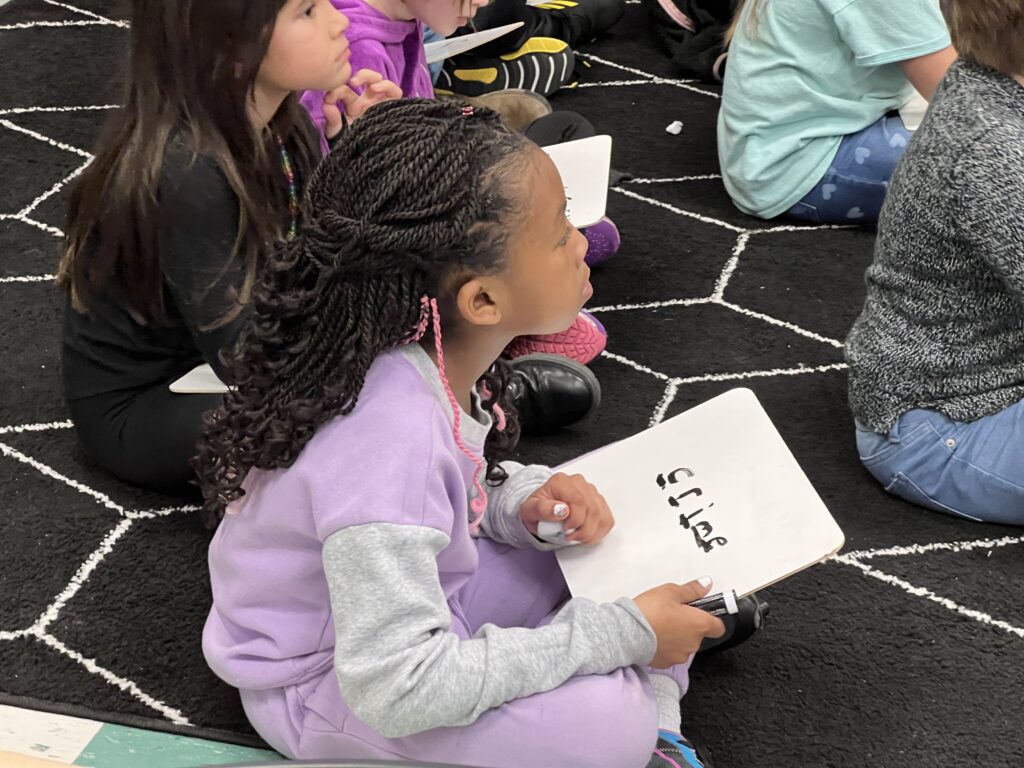

She walks down the hall and opens the door to a classroom where students hold whiteboards in their laps. They’re writing sounds as they hear them.

“(Now) they’ll see those phonemes again during phonics lessons,” Gregory said.

“The next word is CRIME. Can everybody say CRIME?” the teacher asks, following up to ask whether the students know how many sounds are in the word. Sounds, not letters.

The students shout that there are four, and together with the class the teacher walks them through each of the four sounds: /K/ /R/ /EI/ /M/. She instructs the students to mark four blanks on their whiteboard and write down the letters for each of the four sounds.

“Good,” she says as she scans the students’ work. She’s about to move on before she spots one little girl’s board. It reads, “CH – R – I – M.” She’s going to come back to the ending letter, but first she wants to talk the students through the beginning sound.

“Check it out,” she says, pointing at her mouth. “Do we say CH or do we say C?” She then breaks it all down, very explicitly. “What do your lips do? Think about your lips. How are your lips forming? Where’s the sound coming from? Is it from your throat – C? Or is it your teeth and lips – CH? Think about your sounds.”

Her student mimics the sound, erases her CH and replaces it with a C.

How will districts monitor practice against the evidence?

While districts search for ways to ensure that what teachers implement shows fidelity to good research, they’re also working on ways to monitor how it’s showing up in classrooms.

In Clinton City, Melenas says this happens through districtwide walkthroughs.

“So knowing we’re only a year into it, there are many, many things that we’re not expecting to see yet,” she said. “But if we don’t look for them and at least provide that as an expectation, I think we would miss the boat.”

District and school leaders have long done walkthroughs in Clinton City Schools, but they’re looking for an entirely new set of things now. On the walkthrough checklist, these additions fall under the title “Science of Reading.”

The checklist sets forth practices to follow and practices to avoid that align with an implementation guide called “Making the Shift,” published by Amplify.

The district’s executive cabinet, including the entire curriculum and instruction team, does a minimum of five walkthroughs a week. The superintendent probably does more than that, Melenas says.

“It’s really important for us to be visible, to know what’s happening in classrooms, and then to really identify areas that we can support,” she said.

By looking at data trends, Melenas said, the district can determine where teachers might need more training or professional development. And she intends to offer support multiple times, because teachers — like students — may need to see information more than once.

“We’ll just keep bringing that back up so it isn’t something that’s just lost,” she said.

Educators fear another false start

While teachers report feeling optimistic about the direction of reading instruction in their schools, many say they need more time and, often, better materials to truly align with the research. Some say they appreciate LETRS, but still want to know that their districts are independently vetting classroom practices against research.

It’ll take time for all of that to fall into place.

“It seems like that’s a long time, but you’ve got to have time to get this implemented and let it work for the students,” said Katie McLam, Whiteville City Schools director of curriculum and instruction. “You can’t expect that to happen overnight.”

Teachers feel pressure, though, sensing that lawmakers and policymakers — and parents — want to see outcomes quickly. That creates anxiety because states or districts sometimes abandon reforms before teachers have a chance to fully establish them.

“It’s hard to get them to believe – truly believe – that this isn’t going to be the next thing that goes away,” Stanly County’s Plummer said. “But this has got to be able to maintain and sustain itself moving forward because whether a program comes and goes or not, that’s one thing, but the science is not going to immediately change.”

Plummer said he hopes districts are given time to implement over the next few years, and then the state understands it will be a few more years after that for incoming kindergartners to matriculate to third grade before scores show significant gains.

Stanly County started its science of reading journey about two years ahead of the state. Plummer said he knows what’s ahead if the state exercises some patience.

“Imagine the day when we get to where all the energy and time that we’re spending on the (training( can then be put back into the classroom and what we’re doing with those kids,” he said. “(Teachers are) not going to be doing the reading, they’re not going to do the online modules and the bridge to practice. They will be putting it into practice. And it won’t be about me learning, it’s about me putting it in practice for those kids.”