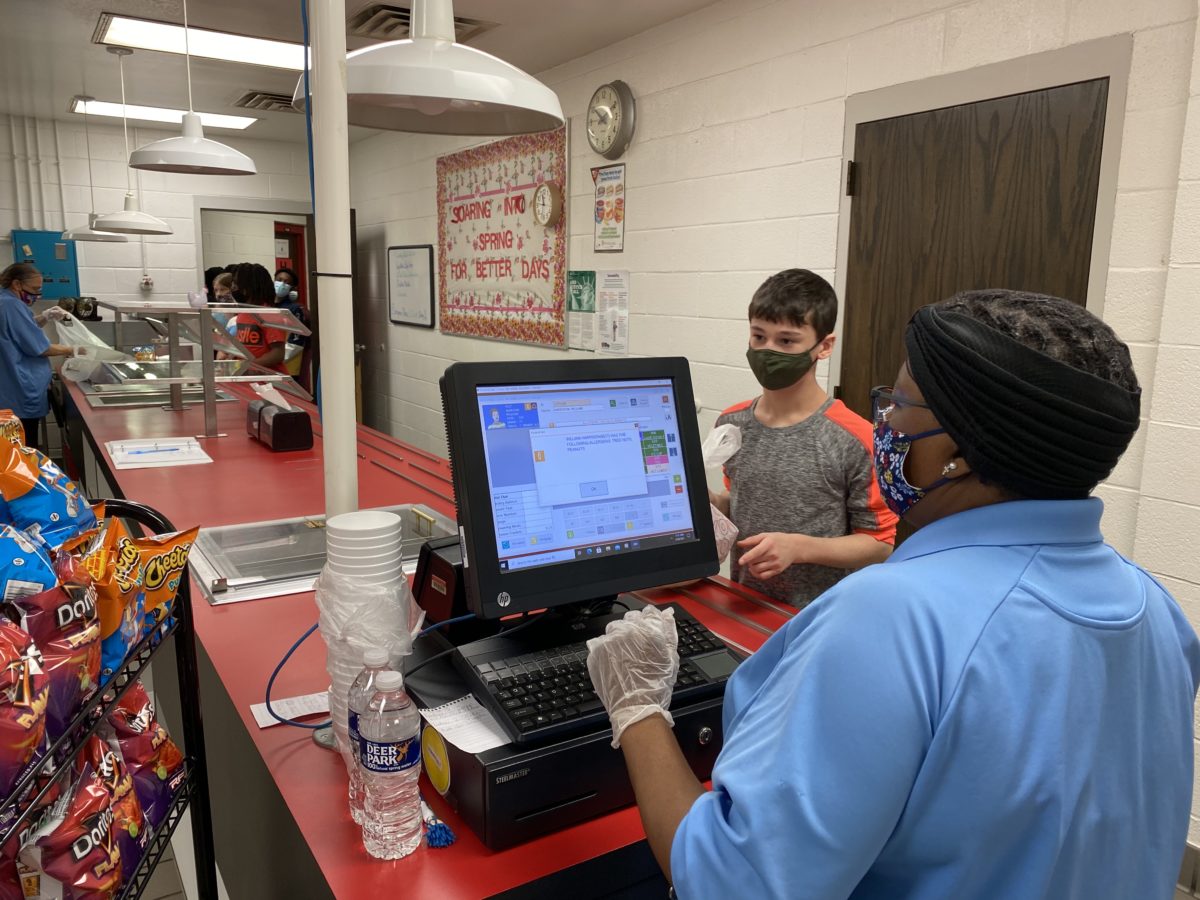

With a new school year underway, cafeterias are once again filled each day as students move through the line to receive breakfast and lunch. But a flurry of policy changes at the state and federal levels are impacting the delivery of school meals, including who has access to free meals.

During the 2023-24 school year, the most recent available data, North Carolina schools served 73.1 million breakfasts and 128 million lunches, the vast majority of which were provided for free to students from low-income families. Research shows that school meals have many benefits, including alleviating food insecurity, supporting good nutrition, and increasing student achievement.

As the school year begins, here is a look at three major policy changes impacting school meals in North Carolina.

Cuts to SNAP and Medicaid will impact access to free meals

The federal budget reconciliation bill, signed into law by President Donald Trump on July 4, 2025, cuts federal funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by $186 billion through 2034. That’s about 20% — the largest cut in SNAP history.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Some of these cuts stem from a major restructuring in how SNAP is funded. Historically, the federal government has fully funded the cost of SNAP food benefits, the money households use to buy food, while states pay half of the costs of administering the program. Under this law, beginning in October 2027, most states will be required to pay 5-15% of food benefits based on their SNAP payment error rates. The bill also increases states’ responsibility for administrative costs from 50% to 75%.

According to estimates from Gov. Josh Stein’s office, North Carolina may owe an additional $420 million annually to fund its share of SNAP benefits. This is on top of increasing administrative costs, which are fully funded by counties in North Carolina rather than the state. According to a memo from the National Association of Counties, North Carolina counties are projected to owe an additional $96 million to cover the increase in administrative costs.

If the state and counties cannot pay that, SNAP would end entirely. The program currently provides food assistance to 1.4 million North Carolinians.

In addition to alleviating hunger, SNAP also plays a crucial role in supporting jobs and local economies across the grocery, agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation industries.

According to a June letter sent to congressional leadership, signed by Stein and 22 other governors, “If states are forced to end their SNAP programs, hunger and poverty will increase, children and adults will get sicker, grocery stores in rural areas will struggle to stay open, people in agriculture and the food industry will lose jobs, and state and local economies will suffer.”

The law also includes nearly $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid, a program that provides health coverage to eligible low-income individuals, including children in low-income families. Stein’s office estimates that 520,000 North Carolinians could lose their health insurance due to changes in Medicaid.

Read more

How are these cuts related to school meals?

Cuts to SNAP and Medicaid impact one of the fundamental ways that students access free school meals: direct certification.

School districts are required to conduct regular direct certification processes to automatically enroll students in free school meals based on their household’s participation in other programs — without collecting household applications. This involves matching student enrollment records with databases for SNAP, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR). North Carolina also allows for direct certification for free or reduced-price meals via Medicaid records.

While direct certification will continue, fewer students will be directly certified for free or reduced-price school meals as participation in SNAP and Medicaid declines.

Students will lose automatic access to free school meals and SUN Bucks

Students in households that lose access to SNAP or Medicaid will lose their automatic access to free or reduced-price school meals and SUN Bucks, a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) program that provides $120 per eligible child in grocery benefits that can be used in the summer months when schools are out.

Instead, families will have to submit applications to remain eligible for free school meals. After previously receiving free school meals automatically, some families may be unaware that they need to complete an application. Others may face barriers in submitting applications, such as limited English proficiency or challenges providing a record of their income.

A return to applications also requires school nutrition departments to dedicate significant staff time and resources to collecting paperwork, conducting income verification, entering data, and following up with families. A 2019 study commissioned by the USDA found that many school food authorities reported being “overwhelmed” during the early part of the school year due to their focus on collecting and processing school meal applications.

“In North Carolina, more than 850,000 students qualify for free school meals because their families participate in SNAP. If those benefits are lost or restricted, families will be forced to navigate complex applications and income verification processes just to access school meals,” said Tamara Baker, project and communications director at Carolina Hunger Initiative, in a statement. “The result? Children fall through the cracks.”

Fewer schools will operate under the Community Eligibility Provision, reducing access to free school meals

The Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) allows eligible schools to serve all students free breakfast and lunch without collecting applications. This provision is increasingly popular nationwide — in the 2024-25 school year, just over 80% of eligible North Carolina schools adopted the provision, providing free school meals to all students at 1,895 schools across the state.

CEP is also directly tied to SNAP and Medicaid participation. That’s because CEP eligibility and reimbursements are calculated using the Identified Student Percentage (ISP), a formula based on the number of students directly certified for free meals, such as by participating in SNAP or Medicaid.

With fewer families receiving SNAP or Medicaid, fewer students will be directly certified for free school meals, causing ISPs to decline. This has two primary effects:

- Some schools may lose their CEP eligibility if their ISP falls below the required 25% threshold. While the extent to which schools will lose their eligibility is not yet known, WRAL reported that Wake County Public Schools projects four schools are at risk of losing eligibility for CEP.

- Other schools that are still eligible for CEP may no longer be able to afford to operate the program. That’s because the ISP also determines the amount of federal reimbursements a school receives. As ISPs and federal reimbursements decline, it may be too expensive for a school or district to serve free school meals to all students, causing them to opt out of CEP.

As schools transition off of CEP, they’ll return to collecting applications to determine eligibility for free and reduced-price meals, reducing access to free school meals.

“School districts right now are … thinking about, ‘If this happens, and we lose … 20% of our ISP, and that’s going to impact our reimbursements — are we going to be able to sustain this program?’ And unfortunately, I think the answer is going to be no,” said Tara Thomas, senior government affairs manager for the American Association of School Administrators, in a webinar. “That means an entire school is going back to the free and reduced-price model, and they’re losing all of the benefits that we know come from healthy school meals for all.”

Other federal cuts will make it more difficult to source local food

In March, the USDA canceled $660 million for the Local Food for Schools Cooperative Agreement Program (LFS). Started in 2021, the program provided funding to states to purchase local foods for use in schools, helping farmers sell more of their products to schools and expanding local and regional food markets.

More than 40 states, including North Carolina, signed agreements to participate in LFS in previous years. In October 2022, the USDA awarded $5.6 million in LFS funds to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA&CS). If the program had not been canceled, North Carolina was set to receive an additional $18.9 million over the next three years to purchase local food for schools — including $12.4 million for K-12 schools and $6.5 million for child care facilities.

In an undated executive summary to the USDA, NCDA&CS wrote that “procuring needed items for school lunches has been a significant challenge due to supply chain issues” and “building partnerships with local suppliers is another excellent benefit to this program as it reduces operating cost and the expense of deliveries at a time when fuel costs are reaching record highs.” Without this funding, it will be even more difficult for schools to purchase local food, which is often more expensive than products available through large national distributors.

In the face of reduced federal funding, NCDA&CS continues to operate the NC Farm to School Program, which helps schools purchase North Carolina-grown crops during 22 weeks of the school year, including strawberries, apples, sweet potatoes, collards, and more. There are also state-level efforts to increase funding for local food purchases. House Bill 774, titled “School Breakfast for All,” includes a $5 million farm-to-school provision that would help schools incorporate locally sourced products into their breakfast programs.

“As lawmakers continue their work on a full budget, we hope they will include a farm-to-school and technical assistance provision, which would support North Carolina’s crucial agricultural industry, including the potential sourcing of locally grown fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy, and proteins for school meals,” said Abby Emanuelson, executive director of the North Carolina Alliance for Health, which leads the state’s School Meals for All NC coalition.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

North Carolina students who qualify for reduced-price meals will continue to receive them for free

In North Carolina, students who qualify for reduced-price meals will continue to receive them for free rather than owing co-pays. In 2011, a state law made school breakfast free for students who qualified for reduced-price meals, and in 2023, the legislature allocated an initial $9 million over two years to make school lunch free for students who qualified for reduced-price meals.

In North Carolina’s 2025 mini-budget, the legislature maintained this coverage, directing school districts to provide free breakfast and lunch to students who qualify for reduced-price meals. The bill also directs the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) to use funds appropriated to the State Aid for Public Schools Fund to cover this cost “if funds from alternate sources are insufficient.”

In July, the USDA announced 2025-26 income eligibility guidelines for free and reduced-price meals. Children in households with incomes at or below 130% of the poverty level are eligible for free school meals, while those in households with incomes between 130% and 185% of the poverty level are eligible for reduced-price meals. For a household of four, earning less than $59,478 annually qualifies for reduced-price meals, and earning less than $41,795 annually qualifies for free meals.

DPI has a list of frequently asked questions about eligibility for free and reduced-price meals available here.

Other issues we’re watching

Efforts to secure free school meals for all students

Nine states — California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Vermont — have passed permanent legislation that provides free school meals to all students. Dozens of other states, including North Carolina, have introduced bills that would do the same. Advocates cite numerous benefits of free school meals for all, including ensuring access to meals that can support students’ learning and health, reducing stigma in the cafeteria, eliminating school meal debt, and more.

In April, House Bill 774, which would provide free breakfast to all public school students in North Carolina, was filed with bipartisan support and referred to the House K-12 Education Committee. Another bill, House Bill 713, would provide both free breakfast and lunch to public school students, but this bill has only Democratic sponsors. However, both bills failed to make the May deadline for crossover, leaving them with little chance of becoming law this session.

The nonpartisan School Meals for All NC coalition advocates for all North Carolina public school students to have access to breakfast and lunch at no cost to their families. The coalition is co-led by the North Carolina Alliance for Health, The Center for Black Health & Equity, Carolina Hunger Initiative, and A Better Chance, A Better Community.

Read more

Financial sustainability of school meal programs

In a national survey of school nutrition directors conducted by the School Nutrition Association (SNA) in fall 2024, 92.1% of respondents reported concern for the financial sustainability of their school meal programs in three years. The survey found that food costs, labor costs, and equipment costs were the top three challenges for school meal programs, and the southeast region — which includes North Carolina — reported significant challenges with these costs at statistically significant levels higher than the national response.

Child nutrition departments operate financially independently of school districts as self-sustaining, nonprofit enterprises. The primary source of revenue for these departments are federal reimbursements, which are roughly $4.60 for each free school lunch and $2.46 for each free school breakfast, with lower reimbursements for reduced-price or paid meals. Child nutrition departments must use their revenues to cover every cost it takes to serve school meals — including food, supplies, labor, equipment, and other overhead costs.

This often results in tight budgets, and financial pressures have intensified in recent years as the cost of these inputs outpaces annual increases in federal reimbursements. In SNA’s fall 2024 survey, only 20.5% of respondents said that federal reimbursement rates are sufficient to cover the cost of producing a lunch, a decline from SNA’s 2018 survey when more than half of directors cited the lunch reimbursement rate as sufficient.

Implementation of new school nutrition standards

In 2024, the USDA issued updated school nutrition standards to better align school meals with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans for 2020-25. These updates include the first-ever limits on added sugars in school meals and additional restrictions on sodium.

Updates are being phased in gradually through the 2027-28 school year. On July 1, 2025, the first regulation on added sugars took effect, with new product-based limits for added sugars in breakfast cereals, yogurt, and flavored milk. Beginning July 1, 2027, added sugars can make up no more than 10% of weekly calories, and there will be new sodium limits on breakfast (10% reduction) and lunch (15% reduction).

In SNA’s fall 2024 survey of school nutrition directors, respondents expressed high levels of concern about meeting the requirements that will go into effect in 2027, with almost 79% reporting serious concern about the new sodium limits and roughly 65% reporting serious concern about the 10% weekly limit on calories from added sugars. To meet these new requirements, 82% of programs in the southeast region reported an “extreme need” for increased funding, which was 12.6% higher than the rate of programs nationwide reporting extreme need for increased funding.

As EdNC works to follow these topics and other emerging issues in school meals, please reach out to Analisa Archer with any insights you might have.

Recommended reading