Editor’s note: This article is part of a series on the intersections of community colleges and child care. Other articles in the series are available here.

Students at Cape Fear Community College (CFCC) in Wilmington can drop off their children for up to four hours while they attend class, work on assignments, or study for tests.

“It made me excited to go back to school because I didn’t have to worry about my children,” said Morgan Barto, a student parent at CFCC whose two young children attend the drop-in program.

The service is funded entirely by private donations from individuals and grants from the New Hanover Community Endowment and Live Oak Bank. That funding keeps drop-in child care free for students like Barto, who said her children wouldn’t have access to early care and learning if the program came with a price tag.

EdNC visited CFCC to learn why they started the program, how it’s funded, the logistics of its operation, and what advice the team has for other community colleges considering making drop-in care available to their own students.

Why drop-in child care

Mary Ellen Naylor, CFCC’s dean of health and human services, was working on her doctorate degree in educational leadership at UNC-Wilmington when she came to understand the challenge of being a student parent.

She was doing a research project, conducting focus groups with single moms who were also students. Naylor said one of the issues that consistently came up as a barrier for these student parents was child care.

“It kind of resonated with me because at the time that I was going back to school, I had four kids,” Naylor said. “I was working full time and my husband was working full time, so I had resources for child care, but these students didn’t.”

According to CFCC’s most recent student financial wellness survey, 28% of students identified as parents.

CFCC already had a licensed child care center — the Bonnie Sanders Burney Child Development Center — where families pay tuition or use state subsidies to cover the cost of full-time child care. But for parents who would benefit from part-time child care, there wasn’t an on-campus option.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Naylor was in a meeting with CFCC’s Foundation Board. While they discussed the needs of students, she brought up the fact that lack of child care is a common reason students leave school before completing their programs.

Naylor said the foundation’s director mentioned that a donor had recently reached out about providing funding for child care. That was the origin of the college’s drop-in child care program.

“For years now we’ve been trying to look at things we hear from students are barriers to retention, and child care is one of the ones that keeps coming up,” said Jim Morton, president of CFCC. “Why not take it on and figure out how we can fix it, or attempt to fix it?”

Both Morton and Naylor said the Board of Trustees supported the endeavor from the very beginning, so the biggest challenge was finding the right space.

They looked into the possibility of simply adding drop-in care as an option at their licensed child care center, but there were several barriers to doing that.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Because students would be coming and going throughout the day, with different numbers at different dates and times, they realized they would not be able to maintain the level of staffing required to meet the state’s standards for student-teacher ratios in a full-time licensed child care setting.

Another challenge is that they wanted drop-in care to serve a wide age range of students — from 6 months to 12 years old. As Naylor explained, “Our Child Development Center is not set up to be able to take beyond that 4- or 5-year-old child.”

They determined they would need to find a site outside of their existing center. That’s part of why three years passed between the origin of the idea and making it a reality for student parents.

“It took us a while to identify a space,” Naylor said. “It took some time to get the application reviewed and approved for the state, and then to start looking at the logistics… The fact that the initial conversations were happening during COVID probably slowed us down more than anything.”

Funding drop-in child care

Funding started with a commitment from a private donor to give $10,000 per year for 10 years, exclusively for the purpose of supporting child care for students.

Knowing they had that seed of support is what empowered the team at CFCC to pursue offering drop-in child care — but they knew they’d need more funding to make it happen.

The game changer was a $250,000 grant from the New Hanover Community Endowment, a $1.3 billion fund established in 2020 after the sale of New Hanover Regional Medical Center to Novant Health. CFCC received that grant in 2023 and again in 2024.

That was followed by a $30,000 grant per year for two years from Live Oak Bank.

Naylor said in the first year, the total cost of running the drop-in program was about $176,000. That included preparing the site, hiring and paying the staff, and all additional materials for the program. The original classroom was located on the second floor of a campus building, which meant they could only enroll students who were reliable walkers — those ages 2 to 12. The space was also small, limiting them to 20 students.

In the second year, the total cost was about $157,000. They moved to a larger, first-floor site and added more staff, but they didn’t have as many new materials to purchase. That space — a large, single classroom set up with different “stations” for students — now accommodates up to 40 students and includes those as young as 6 months.

The current staff includes a full-time director with a salary of about $49,000, a full-time lead teacher with a salary of about $33,000, and four part-time teachers, each paid $15 per hour. Staff members have the opportunity to attend the same health and safety trainings that are required for teachers at the licensed child care center. Staff members are state employees with access to corresponding benefits.

According to the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, the median wage for North Carolina’s early childhood education workforce in 2022 — the most recent year for which data is available — was $12.31 per hour, and the living wage for a single adult was $15.82. The Bureau of Labor Statistics lists the average hourly wage for North Carolina’s child care workers in 2024 as $14.20.

Naylor said labor is the main expense for the drop-in care program, which is typical for all forms of early care and learning.

How drop-in child care works

The program accepted its first students in July 2023. Naylor said doing a “soft launch” during the slower summer months gave them a chance to learn a little about what worked well and what needed to be adjusted before the traditional school year.

Morton said one of the biggest challenges they had in starting drop-in care was finding a location, but that’s a problem they’re actively solving.

The permanent home of the drop-in site will be right next door to the Bonnie Sanders Burney Child Development Center. The 2,550-square-foot space is being specifically designed for drop-in care, and will also include a 3,000-square-foot outdoor learning environment. There will be a bathroom outfitted for both children and adults, plus a kitchen area with a sink and a custodial closet with a floor drain.

Like its predecessors, the space will be a single classroom with different areas for different activities, but this one will also have a more enclosed quiet section designed for infants. CFCC expects it to be ready in 2026.

Both the Bonnie Sanders Burney Child Development Center and the drop-in program use Brightwheel, a child care management software application for parents, teachers, and administrators. Naylor said the service costs the college $179 per month.

Student parents looking for drop-in care complete a form on CFCC’s drop-in care website, which includes a space to upload their class schedule to prove they’re currently enrolled at CFCC. The form also asks for basic information about their child, including name, age, medical information, and pick-up and drop-off permissions.

After submitting the required information, they receive an invitation to join Brightwheel. From that point on, they use the app to register for the drop-in slots, which open up each Sunday for the following week. Students select the dates and times that work best for their schedules within the 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. operating hours of the program.

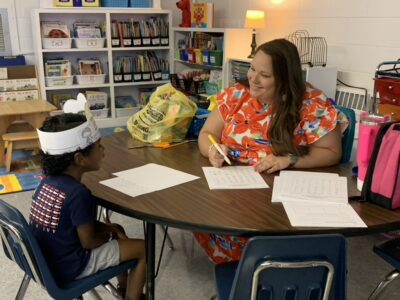

The program appears to be meeting the college’s goal of recruiting and retaining students like Morgan Barto.

Barto graduated high school in 2017, and she was considering going back to school earlier this year when she saw an ad pop up on the CFCC website for drop-in child care.

“I looked more into it and I was like, it’s free? Is this right? Is this actually real?” Barto said. She was in such disbelief that she called the program’s director to confirm.

For most of the last decade, Barto and her husband moved around the country based on his military service as a Marine. Now that he’s medically retired and they’ve resettled in Jacksonville, she’s taking the prerequisite courses for CFCC’s medical sonography program while working part time.

Because the couple is not from North Carolina, they don’t have family or a network of friends to help them care for their two children, 4-year-old Cyrus and 1.5-year-old Leslie. Drop-in care has filled that gap.

“Their first day care experience has been really great,” Barto said.

She said she’s noticed her son’s sharing and caring skills have improved in the two months since he’s been attending drop-in care, and that he’s making new friends. Her daughter has become less shy and more interested in meeting new people.

Barto benefits too. Not only is she able to attend classes, but she’s able to complete much of her homework and studying while her children are at drop-in care.

“I feel like it’s helped me become a better student because I can really focus on my schoolwork,” Barto said.

In addition to expanding educational opportunities for Barto and her children, drop-in care also benefits Barto’s husband by freeing him up from his stay-at-home dad role to give him the time and space he needs as he figures out his post-military career.

And it’s only possible for Barto’s family because it’s free.

Advice for other colleges

For other community colleges considering offering drop-in care to their student parents, Morton and Naylor shared some lessons they learned along the way.

“I would say we probably had a leg up because we have our early childhood education program, and we have the Child Development Center, so we were kind of familiar with which hoops you have to jump through,” Morton said.

The two biggest pain points in getting the program off the ground were finding space and hiring staff. Those are also two of the main issues they’re still trying to navigate.

The drop-in program’s current location was an improvement over the first, but space is at a premium on campus, and everyone is eager for the program to move into its permanent home next to the licensed child care center next year.

And while they feel like they’ve gotten into a “groove” now with consistent staffing, as Naylor put it, turnover is always a challenge in child care. Some of their part-time teachers are also students, who will likely move on to new jobs after graduation.

Another element they’re still trying to figure out is long-term funding. The grants they’ve received in the first few years have been crucial to getting the program up and running, but to keep the program going will require additional investment.

Morton said he thinks of this service as just another form of student support — much like counseling and advising — that can help recruit and retain students, so he’s committed to making it work.

Naylor said CFCC continues to think of ways to go “above and beyond” what is required for drop-in child care when it comes to quality.

“You really want it to be a little bit more than just babysitting,” Naylor said. “It’s not going to be your licensed child care center, but you want to make sure that it’s developmentally appropriate.”

Naylor said there are real benefits to this approach to drop-in care that go beyond doing what’s right for young learners.

“Because if the children look forward to going, it makes it easier for the students to go to class, because they’re not worrying about their child,” Naylor said.

More on best practices

They’ve seen greater uptake among students and greater buy-in across campus and the community as awareness about the program has grown.

“I think that probably from when we first started talking about it, that we didn’t realize the full need and the full impact that it would have for our students and for the college,” Naylor said.

Morton had this advice to offer his fellow community college presidents:

You’re here to serve a community, and to educate and train them so they can have a livable wage and a higher standard of living… Child care is really a big challenge and, next to financial need, that was always one of the higher needs… There are so many issues and other reasons for students to drop out, and so when we find them, we try to pick them off where we can.

For colleges considering drop-in care, Naylor said this:

I would definitely not let not having the ideal spot deter you from starting, because it is a starting point, and that space will let you kind of learn exactly what best fits your population of students… if you have a space that you can just get it up and going, you’ll learn so much from that.

As a beneficiary of CFCC’s free drop-in child care, Morgan Barto had her own advice to offer community colleges:

I think they should consider it because it could give parents that are looking to go back into school the opportunity to go to school and to continue their education without having to worry about the stress of a babysitter, or putting their kids into day care and the financial strain of that.

Editor’s note: The price of Cape Fear Community College’s subscription to Brightwheel has been updated.

Recommended reading