The mood is light in West Craven High School’s halls. Students are talking about weekend plans, laughing and joking with each other. Meanwhile, they’re busy working on something that would be somber if it didn’t occur so frequently: preparing for a hurricane.

“It doesn’t really feel that weird,” said student body president Michael Brown as he walked around campus during campus cleanup and preparation. “It feels like there’s been a hurricane every year, so we’re used to it. It’s like a routine.”

Craven County Schools were the last to dismiss in eastern North Carolina, with every surrounding county except Jones cancelling classes for Wednesday. Jones County dismissed at 11:30 a.m. By noon, West Craven students and teachers were wrapping up their hurricane preparations for the school before dismissing at 12:30 p.m.

Over the last several days, Principal Tabari Wallace and his team created a spreadsheet detailing all preparations required for each room. The spreadsheet was based on questions the schools needed to answer for FEMA after Hurricane Florence hit last year. Wallace said the school is learning how to be better prepared ahead of these storms.

“We didn’t have all these processes in place before Florence,” Wallace said.

On Tuesday, school leaders rode around on a golf cart to assess next steps and took “before” pictures in case they are needed for claims after the storm. Working into Wednesday morning, teachers and administrators started securing the building. Meanwhile, for days, the students had been asking what they could do.

“The kids love to help,” Wallace said. “They were asking when it was time for action so they could prepare their school for the impending storm.”

By third period on Wednesday — around 9:30 a.m. — students got the call. Assistant Principal Montrell Lee broadcast a message throughout the school reminding them: “Students, this is your school. So please help the teachers out.”

Students didn’t need the reminder. By that time, many had been working for hours.

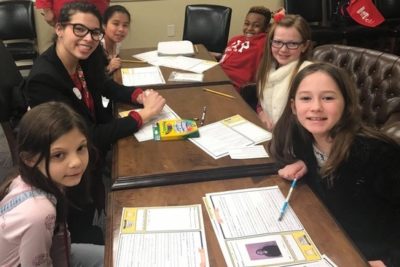

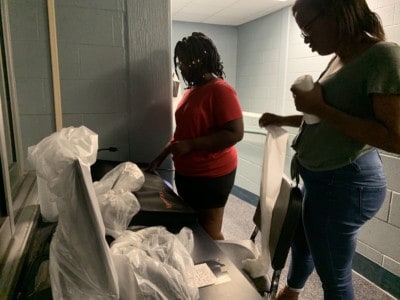

Students carried instruments from the band room to the auditorium stage and covered them with tarps. In the auditorium’s control room, three students busily unplugged all electrical equipment and covered them with plastic trash bags. In the computer lab, students were shutting down computers, unplugging keyboards and bagging everything.

In the culinary arts room, students were moving items onto high shelves and emptying refrigerators. Teacher Shannique Brown started giving food away yesterday.

“We can’t keep the food in here,” she said, drawing on lessons from Florence. “Last year, we came back and the power was gone and it smelled so bad. It took several days to get it out.”

The high school has a robust agriculture education program, with goats, pigs, chickens, and rabbits housed on campus. Students worked to secure the building while instructor Caroline Tart worked to find homes for the animals. One student is taking the goat home to shelter on her family’s farm. Other students are taking small animals, like rabbits, home. Tart will take the pig. And, she lives down the road, so she’ll check on the chickens, who will stay behind.

“They have a survival instinct,” she said. “We have the routine down now. I think I’ve been here six years and we’ve had [a storm] three of those years. So it just becomes a normal thing. I was thinking this morning that maybe we need to go to school during the summer and take these months off.”

As preparations — and the half school day — wound down, the students didn’t appear phased by Dorian’s approach. Some played basketball in the gym while others spoke with friends or finished storm preparations. Most were in the cafeteria area eating lunch, sounding upbeat.

Around them, however, were reminders that it was not a normal day. Classrooms looked empty from the desks down — with bare floors and chairs stacked on top of desks. Higher shelves and desks were packed with computers and classroom supplies.

Teachers have been talking to students about how to prepare at home, and they’ve been keeping them busy with prep work at the school. But Wallace said teachers have also been paying attention to the students’ emotions — because behind the buoyant dispositions might lie more concern than kids are willing to reveal.

“You got to watch kids because they kind of change,” Wallace said. “There’s some swings from excitement to anxiety. Everybody around them and all of the adults in their lives are anxious and they’re going to be a mirror of what they see.”

Recommended reading