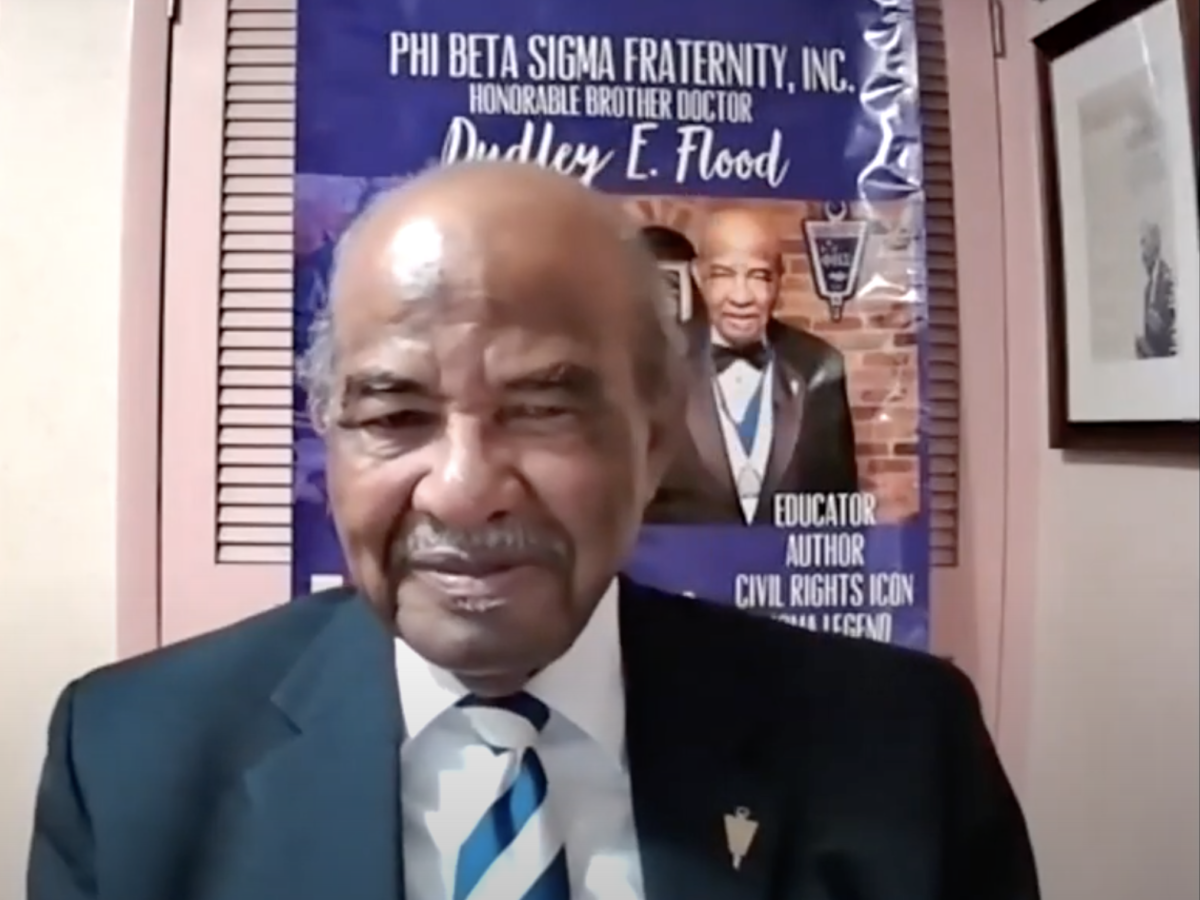

Dudley Flood has held many titles. In 1955, he became a teacher. In the years that followed, he’s gone by coach, principal, and state consultant. But these days, it’s titles of praise that are heaped on him.

District Judge David Baker calls Flood “an icon, a legend, a visionary, and a trailblazer in the field of education. And beyond.”

Baker spoke last week at a virtual ceremony honoring Flood with the 2020 Friday Medal from the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation. Three weeks earlier, the Public School Forum established the Dr. Dudley Flood Center for Educational Equity and Opportunity.

Flood, 88, has been a little uneasy with the praise. He’s proud of his life’s work, which notably includes leading the state’s efforts to desegregate schools. But it’s not something he finds particularly praiseworthy.

“It’s gratifying in a strange kind of way, because you almost feel guilty,” Flood said Friday in a telephone interview with EdNC. “You just feel like what you’ve done is ordinary. It’s what people ought to do.”

A ‘well-deserved honor’

Flood’s career has been well-documented. He grew up in Winton on the banks of the Chowan River and learned to love teaching from his own teachers.

One of them was his mother, who went to a normal school, a school that trained people to teach. Flood’s mother never taught at a school, but with nine children she had a classroom in her home.

One of the lessons she passed on to her son was the empowering nature of education.

“What I found is when people knew better, they do better,” Flood said. “And that’s why I guess being a teacher was the greatest weapon that you could have, although you needed to be fairly knowledgeable and really, really approachable. And not very defensive about having a position. We’re here to discover a position.”

After he built a career in the schools, the Department of Public Instruction tapped Flood as one of three to lead desegregation efforts. Flood traveled the state from 1969 to 1973 to build consensus around the idea of integrating schools.

The stories about his efforts are legend, including a heated gathering in Hyde County when everyone from students, parents and teachers to the Black Panthers and Ku Klux Klan showed up.

Flood used a paddle ball — green on one side, red on the other — to set a constructive tone. He held the red side to the gathering, telling them the ball was green. The crowd remained perplexed until he rotated the ball for them to see.

“If I’m willing to come around here and see how it looks to you, and if you’re willing to come around here and see how it looks to me, we can start to get somewhere,” he said.

Not done yet

North Carolina desegregated its public schools by 1974. But integration, Flood said, remains elusive. That’s why he’s still working.

“I didn’t get into education for a tour of duty,” Flood said while accepting the Friday Medal. “I got into education for the duration.”

Flood speaks often of the Supreme Court’s two landmark decisions on school segregation in the mid-1950s. In Brown v. Board of Education, the court ruled that segregated schools could not be equal. In Brown II came the mandate that states move with deliberate speed to dismantle segregation, and remove the vestiges of that system.

Yet, six and half decades later, the vestiges remain. Racial inequity is embedded in nearly every, if not every, aspect of the education system. Data show disparate opportunities and outcomes for students of color, and student experience backs up the data.

Integration and an equitable way forward are what Flood hopes to see.

“I don’t feel that it’s done,” he said. “As matter of fact, I didn’t feel that it would be done when we were doing that. Keep in mind, my job by definition was desegregation. Now, since learning is concomitant, I found you can teach two things at the same time. While teaching to desegregate, I spent every minute teaching how you integrate. When I left, I’m not aware of anybody having done the latter. There may be some, but I’ve been in hundreds of settings in which that didn’t happen.”

The work is harder today

Flood sees a changed dynamic in policy making. Today, he says, too many people look primarily at how a rule will affect them rather than how it will affect society, or a community, or a school.

When policy makers and constituents are more concerned with their image or their finances, the implications of policy can have harmful effects — or allow harmful policies to linger.

“We didn’t run into much of that because those vested interests were not generally things of which you’d be that proud,” he said. “When I’d give you an opportunity to share with me what your stake in this was, it would almost never be, ‘I’m just a blatant racist.’ It would never be that. It would be almost always, you know, ‘I don’t see any evidence that this will work better.’ OK, we can work with that. I can get you some evidence.”

But personal vested interests today are veiled by arguments that don’t always invite discussions involving evidence, he said.

Nevertheless, he remains optimistic about the future of dismantling inequities in schools. He just hopes those doing the work today heed some lessons from those who did the work in the past.

Using proven methods from his experience

Chief among those lessons, he says, is to invite conversation — trying first to understand others’ points of view.

“I think it’s not just that we don’t have the courage, but I don’t know that we have the unity of purpose,” Flood said.

That unity over something needing to change is fractured today, Flood said, with a society that is deeply polarized.

When he was criss-crossing the state to discuss integration, he said he never came across any logical person who said there were no problems with the status quo. Today, he says, he knows people he considers rational who don’t even believe the pandemic is real.

“I don’t know that I understand the nature of some of the polarization that appears to be before us now,” Flood said. “So the time was easier in which to make some change when you didn’t have the frozen adamancy of polar positions.”

Flood says he believes, now more than ever, that it’s important that leaders not obsess over agreement. Two people don’t have to agree on a solution to try it.

“It has to be mutually acceptable. Not agreeable, acceptable,” he said. “Because there was never anything that we work with that we expected to get 100% concurrence on.”

Blunt advice for those joining in the work

With people polarized around beliefs, ideals, and even fact, Flood says, it takes a certain kind of leadership and a certain kind of deportment to work toward social justice.

That’s particularly true in conversations about removing the vestiges of segregation.

“You don’t get there by calling names or categorizing people, labeling people, and blaming people,” Flood said. “You’re just not going to integrate by doing that. What you have to do is find areas of commonality. … And when you find those areas of commonality, you build that to be a means bringing consensus to other areas that may not be so common.”

It’s easier to say than to do, Flood concedes, in work that can be emotionally triggering. But while he has the right to feel his emotions, Flood said, he never believed he had the right to fling them at others.

“You view your emotions as private, not public,” he said. “And when you’re in a public setting, if you go in there with the perspective that I’m here to do the most good that I can for the people who are here, not for me, you can come home and kick your cat. But you can’t do that and be effective in public.”

Flood said anyone doing social justice work, and particularly racial justice work, should check in with their ability to set emotions aside — because this work isn’t for everyone. But he believes you can do more damage by demanding and yelling if you’re not careful.

“The reason you can’t is that people don’t always believe what you say, but they believe how you made them feel,” he said. “They remember that. And the less competent the person is, the more cautious you have to be about how you make them feel. You can be 100% right, but if I feel that you’re talking down to me, I don’t hear you.”