Editor’s note: Interviews for this article were originally conducted in Spanish and translated to English by Anya Petrone Slepyan and Julia Tilton.

On a Friday evening in Emma, North Carolina, an unincorporated community west of Asheville, noise echoes across the Porvenir Community Center. Young children play in one room, laughing and shouting in Spanish and English. In the next room over, around 15 adults and children talk and sing in a different language — Hñähñu, an Indigenous language from the Mezquital Valley of Central Mexico.

Families sit together, leaning over textbooks and taking notes as the teacher, Abel González Bueno, writes example sentences on the whiteboard. At the end of the class, González leads his students in a traditional folk song. He says that music can be a great teacher, especially for his adult students who grew up speaking Hñähñu.

“I hear this song and I remember when my grandmother would whistle it. So it transports (the students) in a way,” he told the Daily Yonder. “And I think that it’s also emotional, because they might have been in this country for 20 years without hearing anything like this.”

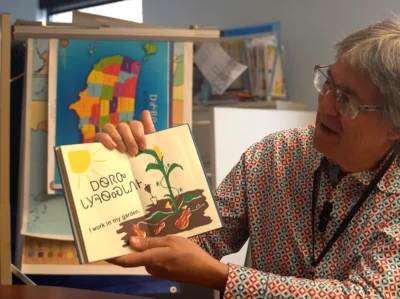

González is the director and co-founder of Ma Hñäkihu, an organization focused on the revitalization and preservation of the Hñähñu language and culture in the Asheville area. They offer after-school classes for children, as well as joint classes for children and adults on Friday nights.

González estimates that there are as many as 100 families in the area who are Hñähñu speakers, or whose recent ancestors spoke the language. But he worries that for many, this linguistic and cultural knowledge is being lost. That’s where Ma Hñäkihu comes in.

“We’ve seen people who are completely disconnected from their own language, their roots, their culture,” González said. “(Hñähñu) speakers are disappearing, and all their wisdom is disappearing with them. So I believe we have an urgent need to revitalize the Hñähñu language.”

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Bringing Hñähñu to the United States

Hñähñu is the most widely spoken Otomí language, and is most concentrated in the Mezquital Valley in the state of Hidalgo in Central Mexico. Although Otomí is itself recognized as one of the 68 national languages of Mexico, it actually consists of nine different linguistic varieties, or dialects. Some of these dialects are so distinct that speakers of one can’t understand the speakers of others, according to Mexico’s National Institute of Indigenous Languages.

The majority of Hñähñu speakers live in rural Mexico, where Indigenous cultures and languages are better preserved, according to González. The Otomí languages as a whole have around 300,000 speakers in Mexico, according to the 2020 census. Though the raw number of speakers grew by 111,000 between the 1895 census and 2020 census, the share of Otomí speakers shrunk from 1.47% of the total population in 1895 to just 0.02% in 2020.

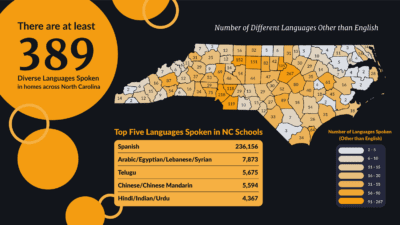

Hñähñu speakers who have immigrated to the United States face a different linguistic landscape. There are more than 1.1 million people of Latin American origin living in North Carolina, more than half of whom are of Mexican descent. This flow of immigration began in earnest in the 1990s, and included Otomí speakers who initially came to North Carolina to work seasonally in tobacco fields.

The U.S. is one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, with over 500 languages spoken, according to the Census Bureau. But despite this variety, linguists have historically considered the United States to be a “language graveyard” because of the speed at which English tends to replace immigrants’ native languages. Though first-generation immigrants generally retain their mother tongue, it is much rarer for their children or grandchildren to do so.

González hopes that Ma Hñäkihu can help the Asheville area’s Hñähñu speakers buck that trend by providing lessons for children alongside their parents.

“I think I need to do this work so that in the next generation, there’s at least one more person who speaks my native language. For young people, it’s about making this connection to a culture and language that is new, but is part of their lives,” he said.

Norma Corona grew up speaking Spanish, not Hñähñu. But she remembers spending time with her grandfather who only spoke Hñähñu, and learning a few words from him. Now, she is attending Ma Hñäkihu classes with her children in the hopes that they can reconnect with the language as a family.

“I really want to learn (Hñähñu) because it is important for my culture, and I also want my kids to learn it. So I feel that I have to learn some so that I can instill it in them and so they can know where they come from,” Corona said.

Related reads

Language, identity, and politics

Languages are cultural, but they can also be deeply political. In March of this year, President Donald Trump signed an executive order declaring English the official language of the United States for the first time in the country’s history.

This didn’t deter Ma Hñäkihu’s work. If anything, González said, it gave them an even greater sense of urgency.

Otomí and other Indigenous languages first received recognition as national languages in Mexico with the passage of the 2003 General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples. But there is still a long way to go to undo historical and contemporary prejudice against Mexico’s Indigenous languages and people. A significant barrier for adult Hñähñu speakers is overcoming feelings of shame associated with their language, according to González.

“This language marks us as Indigenous, and we felt shame when we spoke it. So there’s this fear of saying, ‘Yes, I’m a Hñähñu speaker, I speak my native tongue,’” he said. “We want this shame to go away. It’s a way of healing, perhaps, some of the pain of the past.”

González hopes that the community forming around Ma Hñäkihu’s classes and events will help his adult students reclaim pride in their culture, and appreciate the heritage left by their ancestors.

“I think it’s a way of honoring our ancestors who passed on this language, these customs, all this wisdom that my grandfather once had,” he said.

As part of their mission, the organizers of Ma Hñäkihu maintain ties with Hñähñu-speaking communities in Hidalgo, as well as build relationships with other Indigenous groups in North Carolina. González and others met with Cherokee speakers on the nearby Qualla Boundary to learn about their language revitalization efforts, which include a Cherokee-immersion elementary school as well as classes for adult learners. Ma Hñäkihu also hosts an annual multicultural festival which includes representatives from dozens of Indigenous cultures and languages.

González believes that revitalizing Hñähñu in his community goes beyond cultural and linguistic preservation. It’s also a question of personal freedom in the face of centuries of colonialism.

“I’ve seen the oppression we’ve faced, the colonization where we’ve done only what we’re told,” González said. “We want to give freedom to our own people, including to ourselves, to be who we really are.”

This article is part of Living Traditions, a multimedia project about folklife in central Appalachia. In this series, we bring you an assortment of stories about traditional cultural practices, both time-honored and emergent. Read more Living Traditions.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

Recommended reading