Share this story

- Last month, legislators filed for a bill that would exempt menstrual products from the state sales tax. Until then, students like Finley Townes are providing access to menstrual products in their own schools.

- Period poverty is defined as, “a lack of access to menstrual products, hygiene facilities, waste management, and education.” One @HarnettCoSchool student is tackling the issue in her district.

|

|

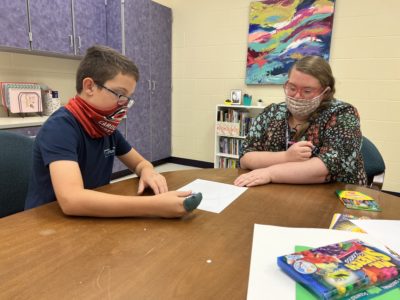

Each day after school, Finley Townes visits the eight women’s bathrooms in her school, where she restocks small bins that contain menstrual products. Townes is a ninth grader at Harnett Central High School. It typically takes her about 15-30 minutes at the end of each school day to visit each restroom on campus.

According to a national survey, one in four menstruating teens struggles to afford menstrual products — up from one in five students in 2019. More than four in five missed class or knew someone who missed class time because they did not have access to menstrual products.

Period poverty is defined as, “a lack of access to menstrual products, hygiene facilities, waste management, and education.”

According to the Alliance for Period Supplies, 17 states have passed legislation requiring schools to provide access to menstrual products. In North Carolina, students across the state are taking the issue of period poverty into their own hands.

Meeting a need

This spring, Townes ran for student council and made providing free menstrual products in all school bathrooms part of her platform. She said the idea was born out of her own personal experience.

“I kind of just got to school here and saw the need,” Townes said. “A lot of people I met in the bathrooms asked me for feminine products. And I thought that if they just had easy access to them, that it could help them out.”

Harnett Central High School provides menstrual products at its front office. However, Townes knew that some of her classmates felt embarrassed making the walk from the office to the bathroom. Providing products directly in the bathroom helps to eliminate this discomfort.

Townes had to seek approval from the Student Government Association and the school’s principal, Catherine Jones, to begin the process.

Townes left a donation box in the mailroom for school employees to donate. Initially, the supply of feminine products was maintained with faculty and staff donations along with Townes’ own contributions.

Jones said students’ reactions have been positive.

“Now, the girls seem to appreciate it. I have had some come up to me and tell me how much they appreciate it, and it’s helped them,” Jones said.

Relying on local community

When the supply began to decrease, Townes reached out to her community for donations. She emailed local organizations, teachers, and even feminine product companies to bring in more supplies.

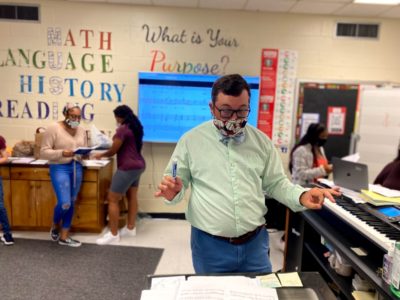

Johnsie Pilkington, a world history teacher at Harnett Central High School, made a post on her personal Facebook. Pilkington appealed to her friends, urging them to donate to Townes’ cause. She was overwhelmed by the outpouring of donations they received.

“I think that people in communities, I think they want to help. They want to help the schools. They want to help students when they can,” Pilkington said.

Pilkington even had former high school classmates reach out to provide supplies.

From local residents to larger organizations, Townes’ stock of feminine products has grown since she first started the project earlier this year. Local organizations, like the Bob Barker Company in Fuquay-Varina and the Fuquay Women’s Club, have donated to the cause.

Pilkington was impressed by Townes’ initiative to pursue this project.

“She did this all on her own,” Pilkington said.

Addressing period poverty in North Carolina

Last year’s state budget provided $250,000 in nonrecurring funds that allowed the Department of Public Instruction to award grants on a first-come, first-serve basis for school districts and charter schools to purchase feminine hygiene products.

DPI reached the funding limit less than one week after sharing the opportunity with schools across the state. Schools received funds ranging from $500 to $5,000. DPI received 134 applications for the grant program and was able to reward funds to 66 schools, according to a state report.

According to the report, “More than half of the grantees indicated that they either have Title I schools in their districts or that many of their students and families are living below the poverty line.”

Grant recipients stated that they would use the funds to purchase menstrual products, including tampons, pads, menstrual cups, reusable pads, and period underwear. Additionally, many recipients stated that the funds would be used for additional items like panty liners, feminine hygiene wipes, deodorant, soaps, puberty education products, and more.

Grantees wrote the funds allow schools to meet students’ basic needs.

“Having access to feminine products at school will reduce attention issues that arise as a result of students not having adequate feminine products and feeling ashamed to leave their home,” Gates County Schools stated in its request for funds. “Finally, access to feminine products will provide safety and comfort to students and increase academic success.”

Lillian Pinto is the reproductive health consultant for DPI. She says these funds allow school districts to support their students by giving them a comfortable environment to learn.

“The more we can do for students and families, to support them to ensure that they have the best opportunity to learn and grow and the best environment possible, I think that is what we hope to achieve,” Pinto said.

There are other initiatives in the state to expand access to feminine hygiene products. State lawmakers introduced the Menstrual Equity for All Act last month. If passed, it would increase funding for the DPI program to $500,000 in recurring funds and eliminate the state sales tax on menstrual products.

With legislation up in the air, students like Townes will continue making efforts to provide access to menstrual products in schools.

Townes said she wouldn’t have been able to build her surplus of supplies without community support. She encourages other students to reach out to their communities.

“Build community support. I think our faculty, teachers, principal, and everyone we reached out to have all been incredibly supportive,” Townes said. “I think without that, I wouldn’t have been able to do it.”