Student success has to do with more than academic instruction and performance. School support personnel provide much-needed services to address other factors of the “whole child” — physical, social, and behavioral health and wellbeing.

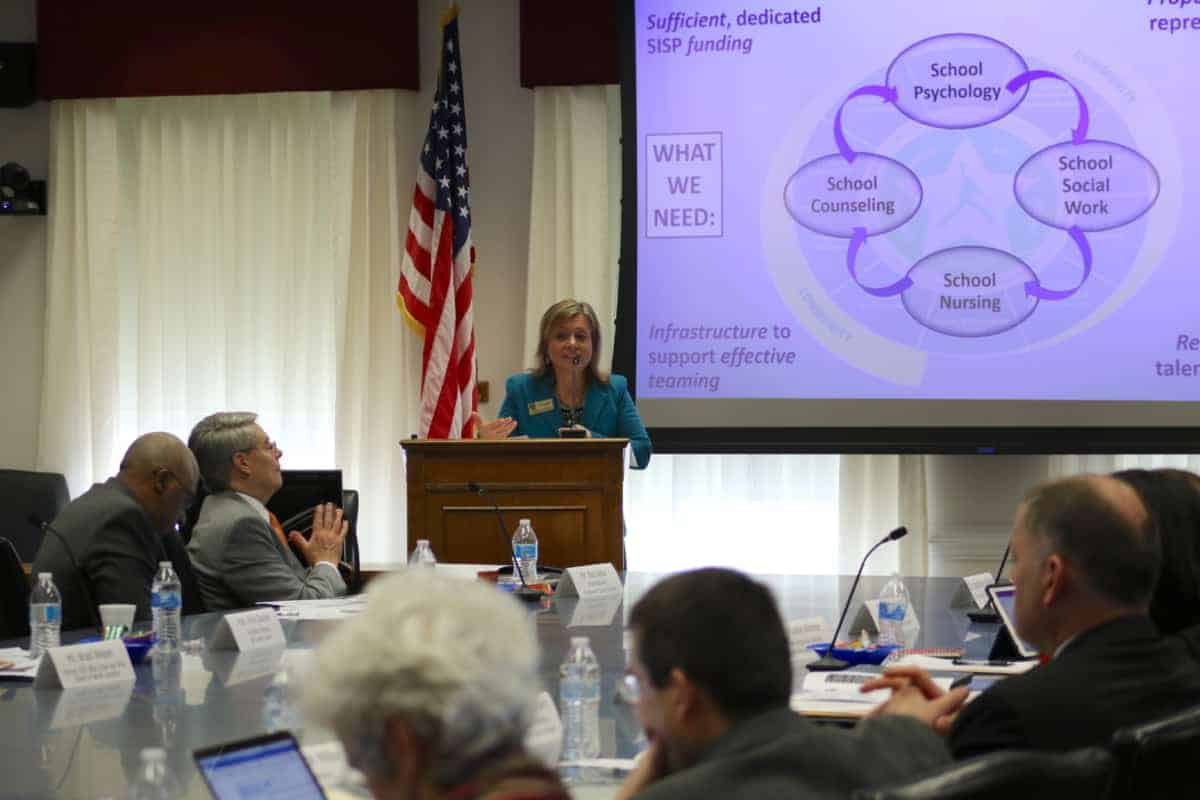

Yet in schools across North Carolina, these “specialized instructional support personnel” (SISP) are stretched thin. In presentations from school nurses, psychologists, social workers, and counselors, the Governor’s Access to Sound Basic Education heard Thursday of the barriers facing SISPs’ work.

North Carolina’s ratios are higher than nationally recommended ratios for each of those roles. And in counties with less resources and lower salaries for SISPs, the challenge of finding enough qualified individuals to fill the positions that are funded is constant.

The Governor’s commission is studying how the state can meet its constitutional duty of providing equal educational opportunity to all students, which the state Supreme Court ruled North Carolina is failing to uphold as part of the ongoing Leandro lawsuit. The case began in 1994 when families from five low-wealth counties sued the state, claiming their children were not receiving equal educational quality as students in wealthier districts.

Ann Nichols, a state health nurse consultant, explained how wealth disparities impact the level of support school personnel receive. For school nurses, she said less-affluent districts struggle to recruit those with higher levels of education and then struggle to retain nurses who are working and going to school at the same time.

“… A couple of the Leandro decision-related counties have this very issue,” Nichols said. “They are a revolving door, they have a hard time hiring somebody. They finally hire somebody but then that person doesn’t have enough support to make it through the educational process to get certified, so then they have to do something about moving on to somebody else, and it’s a constant thing.”

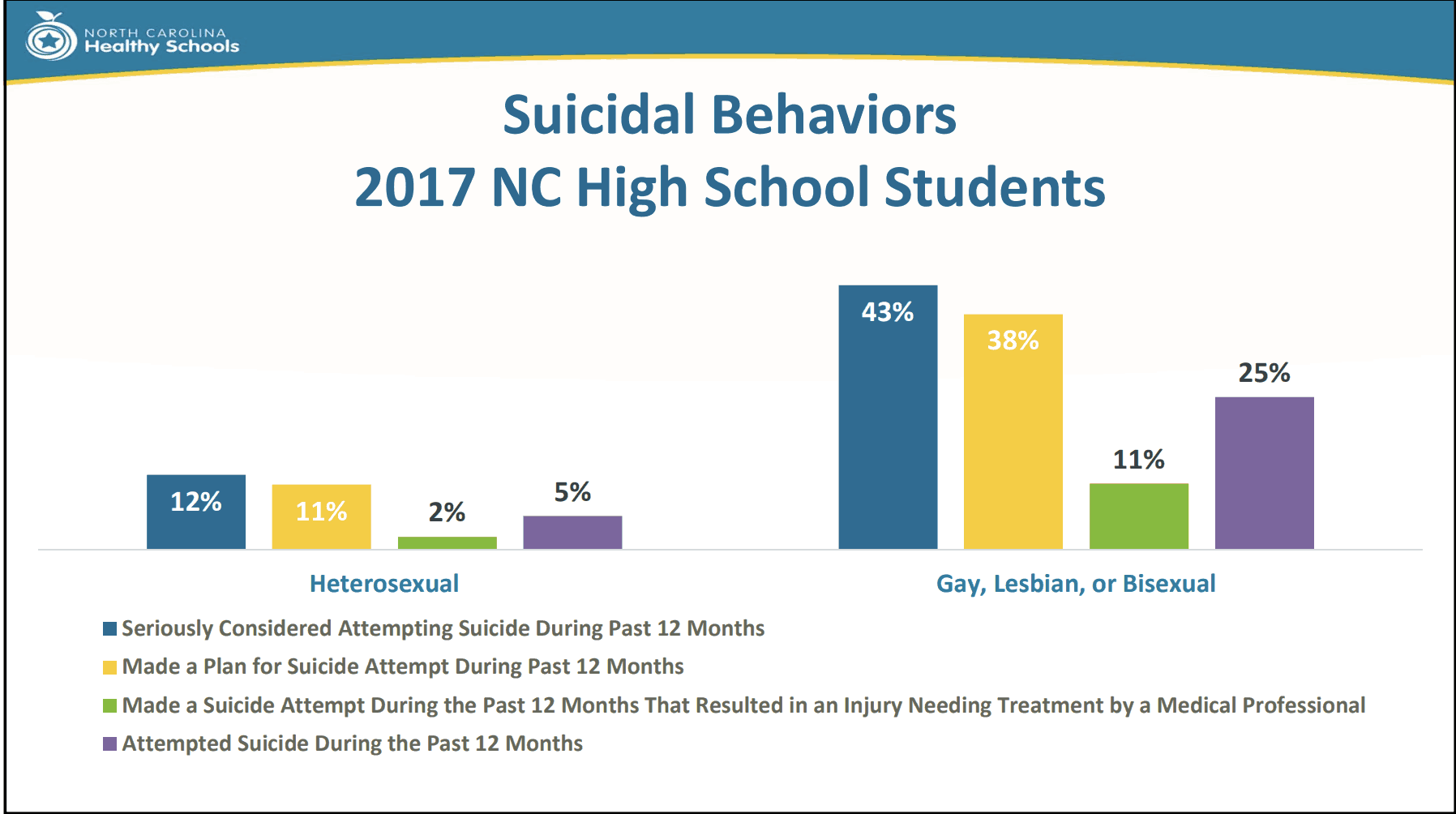

The need for student health support is real. Ellen Essick, the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) section chief of NC Healthy Schools, presented data to kick off the meeting from the annual Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), given to all the state’s middle and high school students. One datapoint stood out: 16 percent of high schoolers in 2017 “seriously considered attempting suicide in the last 12 months.” That’s up from 13 percent in 2007. When asked more nuanced questions, five percent of high school students said they had attempted suicide in the last 12 months. The right chart below breaks down the data for students who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, who are around four times more likely to display suicidal behaviors.

Essick said she often hears from districts who need more knowledge and tools on how to create safe environments for students.

“We have to look at a lot of education tools for school personnel who don’t understand why someone seems to be bullying or what is a safe environment,” she said. “It’s not that they don’t want to help students, a lot of times. As a matter of fact, I get quite a few calls that say, ‘Come and help us understand what’s the best way to support our students.'”

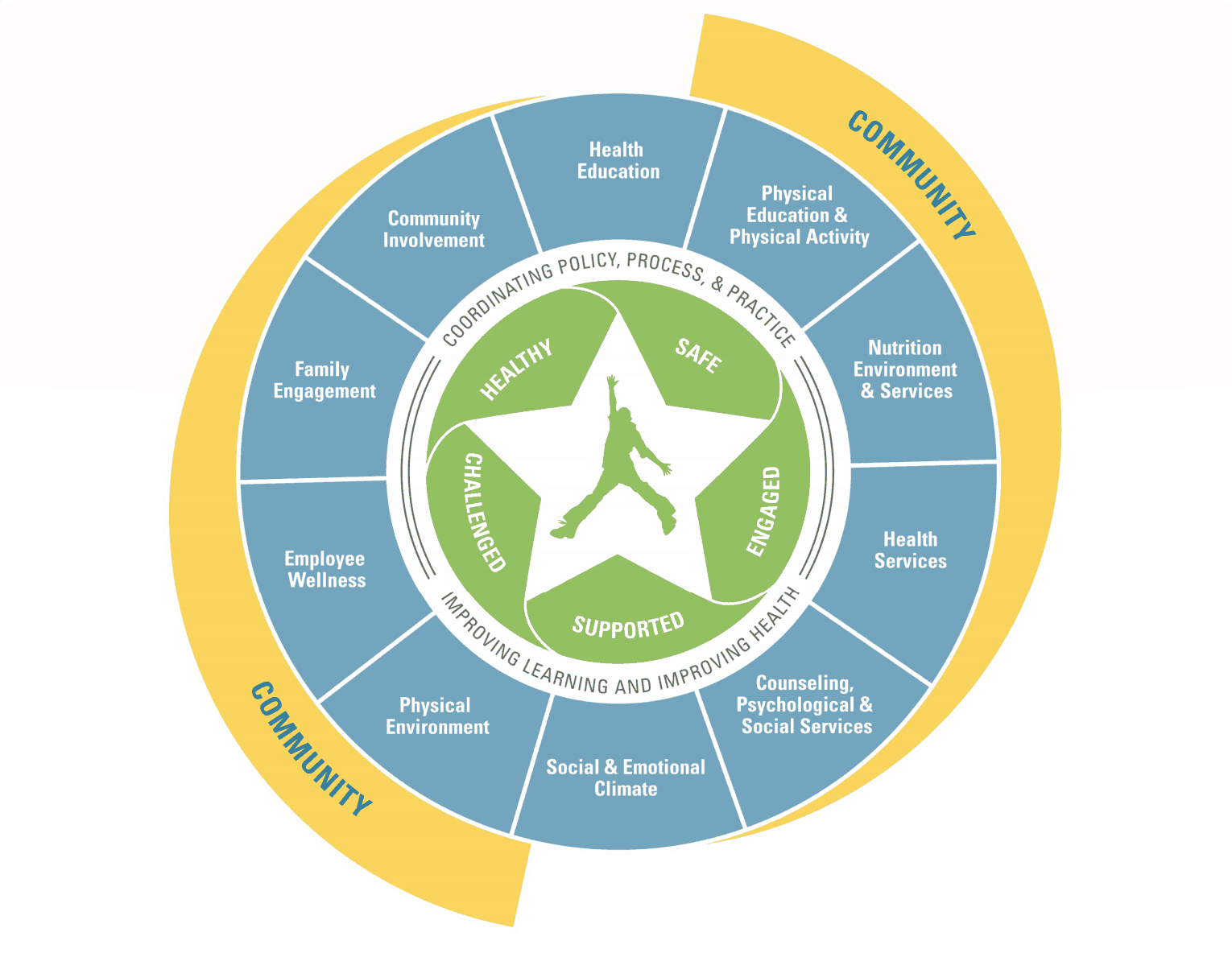

Since 2016, the State Board of Education has operated under a “whole school, whole community, whole child” approach, which comes from ASCD, a national education organization. The graphic below outlines this model, which Essick said “puts each student right in the center.”

The framework is one that all SISPs use to think of their roles in students’ lives.

“If you want a student to be healthy, safe, engaged, supported, challenged, then we’re going to have to look at all those factors that affect them,” Essick said. “Test scores are one thing, but we have to think about all of the things that happen behind those test scores.”

Leaders from Cabarrus County Schools provided one example of a district working to prioritize the physical and psychological well-being of students. They shared the SISP model they’ve been developing over recent years, an aligned and coordinated systemic structure. There are SISP teams at each school, along with a district-level SISP team that supports personnel at the school level. They have required more and better training and professional development for their support personnel. And they’ve implemented an evidence-based threat assessment process for crisis situations.

The county’s Director of Student Services John Basilice described how having district-level capacity with experience in the specific SISP field is important when a school-level professional is in a critical situation.

“It’s not uncommon for me to get a call from a first-year school counselor who will say, ‘I have a suicidal student, I don’t know what to do,'” Basilice said. “And I’ll say to them, ‘Alright, great. Have you taken out your suicide protocol?’ …And boom, all of a sudden, their frustration starts to erode and they remember their training, and they’re in. So they have a resource available and they’re able to do it.”

Find their entire presentation here.

School counselors

School counselors must have master’s degrees to gain DPI licensure and have 15 different preparation programs across the state to choose from. They provide different levels of support and intervention based on students’ varying needs, from crisis counseling to teacher classroom behavior support to career awareness and planning.

“Gone are the days of the guidance counselor that we knew,” said Cynthia Floyd, a state consultant for school counseling as she presented to the commission. “If you see a school counselor cringe when you say ‘guidance counselor,’ it’s because there is a difference. The old guidance counselor, the troubled kids got referred to them, and they helped kids with college applications. They definitely didn’t have a 48 to 60 hour master’s program.”

The nationally recommended ratio for school counselors is 1:250. North Carolina’s average school counselor ratio is 1:367. Floyd said the main barrier to reducing that ratio is funding. Though she did not provide specific numbers, she said she is confident a pipeline exists to fill positions if they were funded to meet the ratio.

Floyd said counselors are expected to be comprehensive in their strategies. That means impacting not just a handful of kids with the highest needs, but analyzing what the entire student population needs and making changes to support those needs through classroom visits, small group sessions, and one-on-one meetings.

“I don’t mean they’re available for referrals,” she said. “They are expected to impact every child in the school.”

Best counseling practices expect professionals to be preventative in their approach, Floyd said. That often looks like teaching conflict management skills before a problem arises and academic support before a child gets too far behind. Floyd said counselors use attendance and behavioral data to drive where they focus.

Floyd said many counselors struggle to do their job well because they are bogged down with administrative tasks. She said school administrators do not receive proper training to acknowledge SISPs’ importance and support them. One of her recommendations is making sure that training, which is part of State Board policy, is implemented in principal preparation programs.

“When you’ve got a million things on a school administrator’s plate, they’re trying to make that whole school day function well, and they don’t have enough people to do it,” Floyd said, adding that funding for more administrative positions is needed in many schools.

“Sometimes it does come out of that necessity that [principals] are trying to find someone who’s not tied to a classroom schedule to help them do those things,” she said. “The problem that comes with that is if they’re doing those things, they’re not doing group counseling for kids, or individual counseling, or classroom lessons on conflict resolution.”

Find Floyd’s entire presentation here.

School nurses

School nurses are registered nurses (RN) and must complete a specialized school nursing certification within three years of being hired by a school. To receive that certification, the nurse must have at least a bachelor’s degree. They are responsible for case loads and health care delivery of students. Less than half (41 percent) of school nurses in North Carolina serve just one school — others serve up to six schools at once. Twenty-two percent of school nurses serve three or more schools.

The nationally recommended school nurse ratio is one per school, or about 750 students. North Carolina’s school nurse ratio ranges from 1:313 to 1:2,724. A General Assembly Program Evaluation Division study in 2017 found the need for school nursing has expanded in recent years and their roles and responsibilities are more complex than ever.

Nichols said the turnover rate for school nurses is significantly lower than other RN positions at 13 percent. Many school nurses love the flexibility of the work, she said.

“There are many highly-qualified and experienced school nurses who are operating to their full scope of practice capacity and well serving students who need that support and educational access,” she said. “But they are often employed in our more resource-rich counties who have access to a bigger pool of qualified candidates. Because of competition for those nurses, salaries for those districts are also generally better.”

She said newer nurses with less experience and lower levels of education can struggle in the position. Nichols continued: “But in other counties, the pool consists of the more-limited associate degree nurse who comes with less exposure to community and populated-based practice principles, and must gain that knowledge through experience and working on a baccalaureate degree. Unfortunately, in a county where the salary is already not competitive with other nurse employers, the funding of that degree also falls to the nurse who may struggle to finish that process.”

Find Nichols’s entire presentation here.

School psychologists

School psychologists in North Carolina are licensed by DPI and, to receive that licensure, must complete a six-year school psychology program that is approved by the state and score a certain level on a state test. They deliver academic and behavioral health services to students. Like other SISP positions statewide, there is a large difference between the nationally recommended ratio of 1:500-700 students and the state’s ratio: 1:2,083 students.

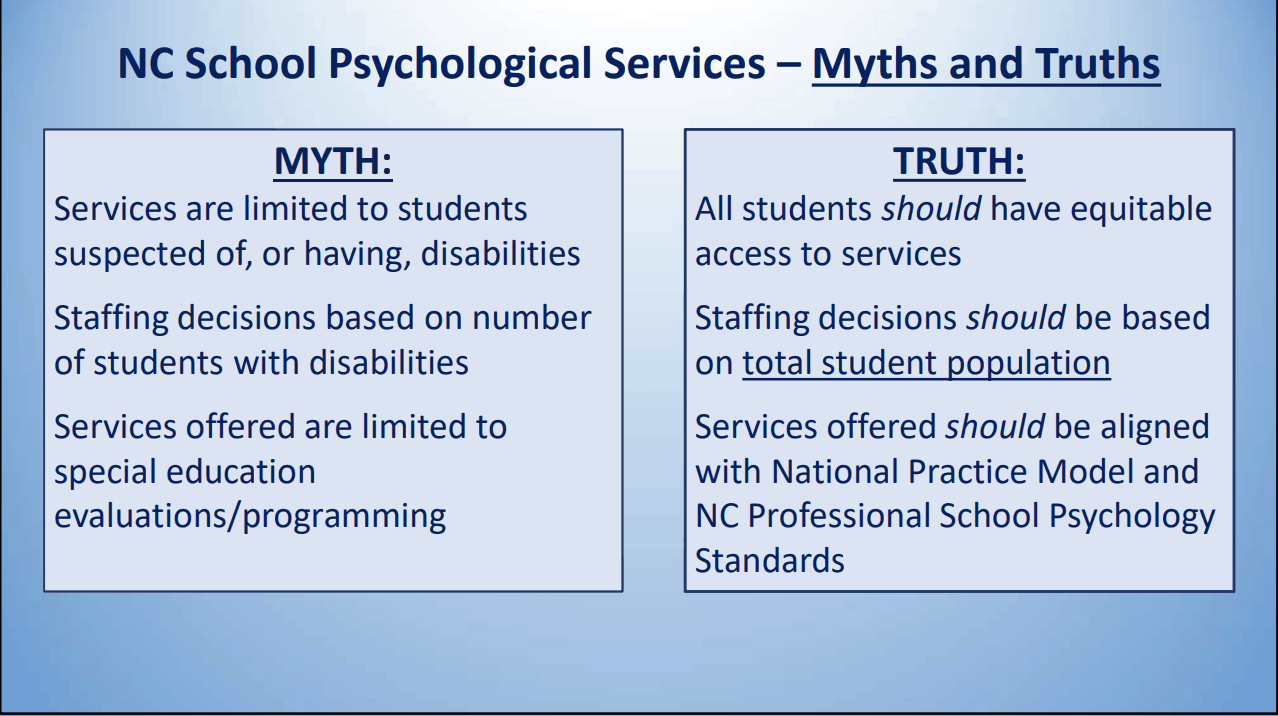

Lynn Makor, a state consultant for school psychology and traumatic brain injury, busted some myths about school psychology at the commission meeting, like who psychologists are supposed to serve, how they are funded, and the scope of their work. From her presentation:

Makor said there is a lack of structure in schools that allow SISPs to work together effectively.

“Like other content-level expert areas, like our literacy folks, or our grade-level teams, they have structures in place that are built in to their system that allow them to work as an effective unit for the greater good of that specialized area that they’re working towards.”

Makor emphasized that even in a model that has too few positions funded, there were 75 school psychologist vacancies statewide last year.

“We can’t forget about our pipeline problems, and we do have them with school psychology in our state. We have five stellar programs in our state. That’s it.” Makor later added: “We don’t have the training programs in our state to support filling the gaps.”

Find Makor’s entire presentation here.

School social workers

The commission heard from Elizabeth Munson, a Wake County social worker who, throughout her career, has served 12 schools at one time, seven schools, two schools, and, finally, just one school. Her experience reflected the other SISP presentations: too much to do with not enough support or time.

Munson said when only the most pressing issues can be completed, attendance is placed as a priority for social workers.

“When a school social worker has many schools, the things that we’re able to do, well they’re not as many, and we have to first comply with that compulsory attendance law,” she said. “And absences and truancy are just the symptom of so many other things that are going on.”

The nationally recommended school social worker ratio is 1:250, and North Carolina’s average ratio is 1:1,427. School social workers usually either have a bachelor’s or master’s degree in social work, though some schools employ Licensed Clinical Social Workers. DPI also issues licenses for school social workers and accepts graduates from six universities across the state.

School social workers support the social and emotional needs of students and engage families to address underlying problems that may interfere with a student’s educational experience. They often navigate health, judicial, and social services to connect students and families with the supports they need.

Munson stressed that she needs other SISPs to do her work effectively. She said her major concerns are the lack of a state consultant from DPI to which social workers can represent their needs and challenges and who can collect statewide data related to social work, the lack of funding for more positions to serve more students and families, and the lack of differentiated pay for social workers with master’s degrees.

Find Munson’s entire presentation here.

Below is an overview from DPI’s NC Healthy Schools on the roles and responsibilities of different SISP positions, as well as the requirements for each to work in North Carolina’s schools.

Recommended reading