Over the past decade, North Carolina’s students have experienced increasing mental health challenges. Data from the 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey showed that 39% of high school students reported feeling sad or hopeless, and the 2025 NC Child Health Report Card found that over 50% of children ages 3 to 17 faced difficulties accessing mental health treatment they needed.

“North Carolina faces a youth mental health crisis,” said Dr. Ellen Essick, section chief at NC Healthy Schools within the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI), in a press release.

Educators who work with students every day agree.

“I feel like the landscape of our students has been changing, so we have just a higher level of mental health needs,” said Jeannie Kerr, director of Project AWARE at Nash County Public Schools (NCPS).

“There has been an increase in mental health needs,” said Cathy Waugh, SISP Coordinator and McKinney-Vento Liaison at Person County Schools. “I think you would get a similar answer from every district.”

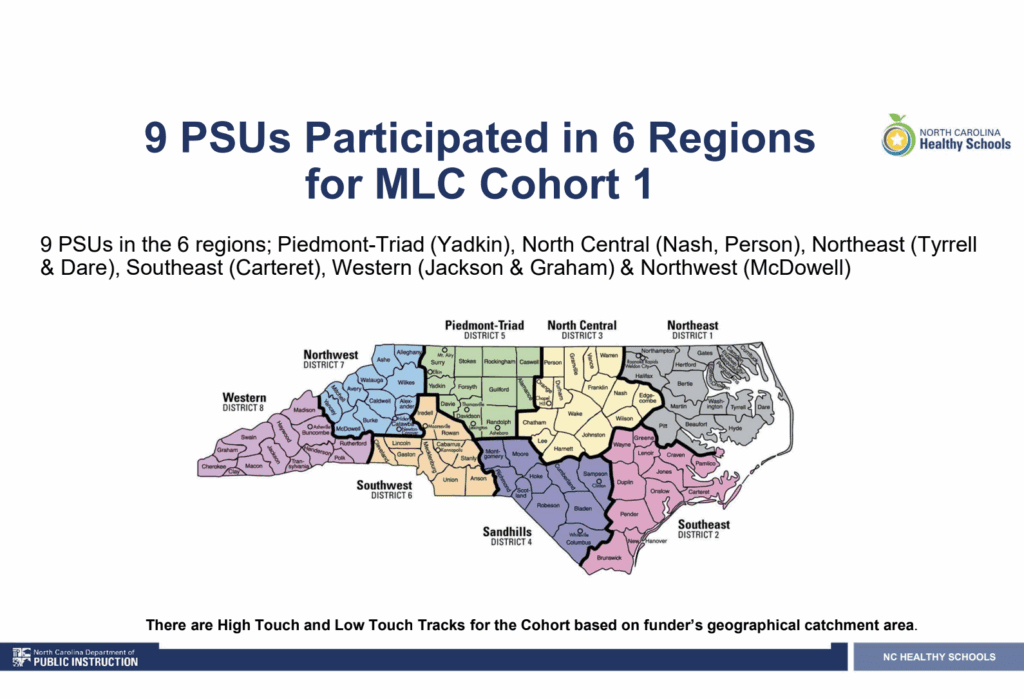

Kerr and Waugh have both participated in the Medicaid Learning Collaborative (MLC), a cohort of districts receiving free technical assistance to help them better understand how to bill Medicaid for school-based mental health services. In its second year, the MLC is now supporting 19 districts and charter schools across North Carolina and is run by the eastern North Carolina based nonprofit Rural Opportunity Institute (ROI).

Initial results from the first MLC cohort are promising, with districts reporting an increase in students receiving mental health support from the previous year and higher confidence completing school-based Medicaid processes. While experts told EdNC it will take multiple years to see the full impact, schools reported “major” impacts on student well-being and noted “anecdotal impact on student well-being, attendance, disciplinary incidents, and academic performance.”

Combined with work at the state level through the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS) to streamline policies and eliminate barriers for districts with school-based Medicaid billing, both ROI and district leaders hope the end result is more students having access to mental health services in schools.

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

HOPE: Where it all began

In 2022, Quarry Williams was the coordinator of the Honor Opportunity Purpose Excellence (HOPE) alternative learning program at Edgecombe County Public Schools (ECPS). Working with students who had been expelled from traditional high schools, Williams saw a dire need for mental health services but wanted to find a solution that was more sustainable than grant funding that would eventually go away.

“What happens with the student when those funds leave?” Williams asked. “The student still has the need. I feel like it is much worse if you get the help that you need and then all of a sudden it goes away. Especially with students that have trauma, that’s another barrier for them — like, this person just left me.”

At the time, Williams was part of ROI’s Resilient Leaders Initiative, a nine-month program for local leaders to identify a complex problem and work with a coach to design a solution. Williams was paired with Dr. Heidi Austin, director of Project AWARE at DPI, and along with support from ROI and ECPS administrators, Williams set up a pilot program to bill Medicaid for student mental health services at HOPE — something few, if any, North Carolina schools were doing at the time.

It worked. In just one semester, HOPE provided 120 counseling sessions to 21 students. Suspensions across all HOPE students dropped by 28% compared to the previous semester, and disciplinary actions fell by 38%.

“What I like about this is it was something innovative, something never done before,” Williams said. “I’m quite sure people had fears of what might happen because it’s never been done before, but they supported this vision. And now you’re seeing it in living color and seeing the possibilities of what can happen.”

From pilot to statewide model

For decades, schools have billed Medicaid for services for students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). In 2014, federal Medicaid policy changed to allow schools to receive Medicaid reimbursement for “covered health services delivered to all students enrolled in Medicaid.”

In 2019, North Carolina became one of 16 states at the time to expand school-based Medicaid to cover services provided to any Medicaid-enrolled student who has an IEP, Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP), Individual Health Plan (IHP), Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP), or 504 plan. Students are six times more likely to access mental health support when services are available on campus, according to Essick, and the 2019 expansion made that kind of support possible by widening the pool of reimbursable services.

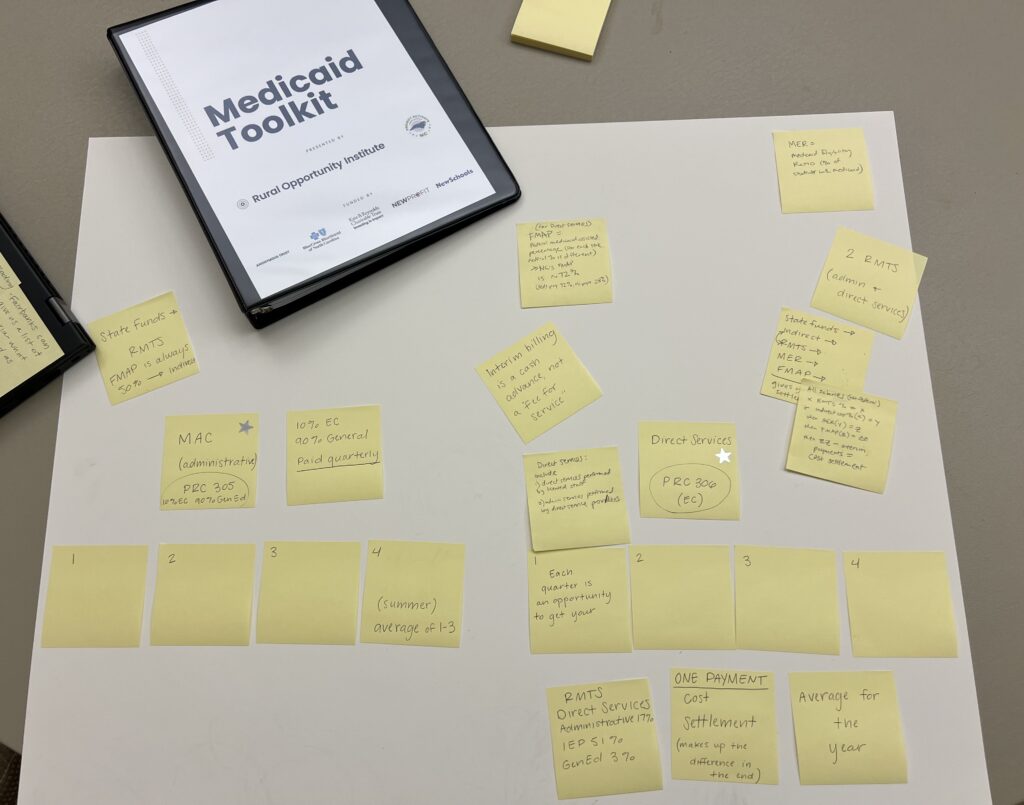

Fast forward to the HOPE pilot program in 2022, ROI realized that the processes Williams developed needed to be documented and shared statewide. They partnered with DPI and DHHS to create the North Carolina Medicaid Toolkit, written by national Medicaid expert Sarah Broome, who learned firsthand how difficult school-based Medicaid billing is after running a school in Louisiana.

The toolkit walks district and school leaders through the complicated and necessary steps to maximize Medicaid reimbursement for school-based health services.

While the toolkit is a powerful and a necessary first step, ROI realized that districts did not have the time or capacity to work through a 100-page document without hands-on support.

“It is an overwhelming document,” Broome said. “You can’t get it any more simple than this — this program is really complicated — but people get really frightened by the size of it and they also need an opportunity to ask questions.”

This led to the creation of the Medicaid Learning Collaborative (MLC). ROI received funding from the Camber Foundation to launch the first cohort with nine districts. Spanning the 2024-25 school year, the collaborative offered monthly virtual sessions, individualized coaching with Broome, and opportunities for districts to learn from one another.

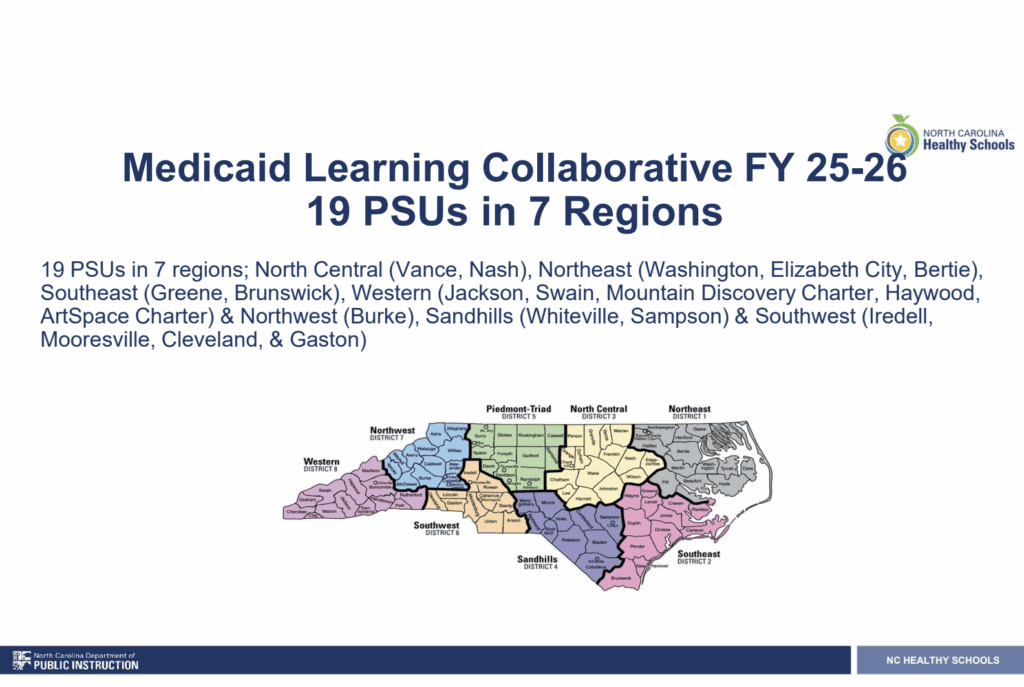

Now in its second cohort, the MLC includes 19 public school units (17 districts and two charter schools) across seven regions of North Carolina. Districts in western North Carolina have joined in higher numbers this year, ROI staff noted.

Participants in the collaborative say that the MLC has increased their understanding of school-based Medicaid reimbursement and has led to more students accessing services.

‘I didn’t even know how much I didn’t know’

EdNC spoke to four district leaders in Nash, Person, and Jackson counties who participated in the first cohort of the collaborative. Both Nash and Jackson returned to join the second cohort after realizing they wanted more of their staff to participate and gain the expertise and insights provided by the collaborative.

All four leaders emphasized the importance of the collaborative in expanding their knowledge of how school-based Medicaid reimbursement works, especially the importance of the Random Moment Time Study (RMTS).

“Nothing about the school Medicaid program works the way that medical insurance works in your personal life,” said Broome. “The language does not make sense to schools, and there is a lot of fear and anxiety about doing it wrong.”

According to Healthy Students, Promising Futures, “RMTS consists of a statewide sample of providers delivering direct and administrative services to determine the percentage of time spent delivering services or conducting outreach and administrative activities associated with the school-based Medicaid program.” RMTS is a key component of the formula the federal government uses to determine how much schools receive in Medicaid reimbursement.

“We all came from community mental health or private practice or other areas where it is a fee-for-service model,” said Meagan Crews, director of mental health at Jackson County Public Schools. “And so we just assumed that Medicaid is a fee-for-service model in schools as well, and so I think that was a huge aha moment in the collaborative.”

Person County Schools is not yet billing Medicaid for mental health services, but Waugh said the collaborative changed their understanding of how school-based Medicaid reimbursement works.

“The biggest change is our district as a whole and our team that we work together here with have a better understanding of the Medicaid billing process,” said Waugh. “It’s helped us to grow as a district and have a clearer understanding so that we can maximize the services. … If we do choose to move to billing for the mental health services directly, then we have knowledge of how to do it.”

Nash County Public Schools (NCPS) had already been billing Medicaid for services, including Occupational Therapy (OT), Physical Therapy (PT), and speech language. However, billing for mental health services, especially for students without IEPs or 504s, was new territory.

“When I first started this, I was thinking, ‘I’ve been doing this for so long, I may learn a few things out of it,’” said Christy Grant, executive director for student support services and exceptional children at NCPS. “But what I learned from this was very different. I thought I knew Medicaid… but the things they taught us, I didn’t even know how much I didn’t know.”

“What was really important for us,” Kerr, director of Project AWARE at NCPS, said, “was seeing how we could provide services to students who didn’t have a 504 or an IEP. All students need access to mental health support, and now we can provide the same high-quality support for general ed students.”

For Crews and her team in Jackson County, what they learned through the collaborative resulted in them completely changing their referral process.

“After participating in this collaborative and having these aha moments of how we were creating unnecessary hardship for our school teams, for our families, it was midyear last year, I think, over the Christmas break, when we just revamped it and removed all those barriers, and we saw the number of students receiving services increased significantly,” Crews said.

District leaders highlighted the importance of both the one-on-one coaching with Broome and the network they developed with the other districts through their participation in the collaborative.

“The relationship building was great,” Waugh said. “I can text other districts now and ask, ‘How are you handling this?’ even if it has nothing to do with Medicaid, just mental health. And having access to Sarah, having the opportunity to talk to someone who is an expert, that is pretty awesome for rural districts.”

Each district was tasked with developing their own Medicaid toolkit, and the ability to meet with Broome one-on-one to go through their policies and cost reports was “impressive,” Grant said.

“To have that level of technical assistance, that’s how we truly learned and we’re able to really have that level of understanding,” she said.

Other districts shared similar experiences in qualitative surveys from the first cohort. Participants reported increased confidence in navigating Medicaid processes, especially in responding to the Random Moment Time Study, and more students receiving mental health support.

Updating NC’s Medicaid plan and dealing with the uncertainty surrounding federal Medicaid cuts

In 2024, NC DHHS received a $2.5 million grant from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to expand school-based health care in North Carolina. One of the goals of this grant, according to Austin, is to update the state’s Medicaid plan to make it easier for districts to get reimbursed from Medicaid for school-based mental health services. She also said she hopes the grant will lead to a permanent state position for Medicaid technical assistance for districts, since right now DPI does not have a full-time equivalent position for technical assistance.

One of the most important goals in updating the state’s Medicaid plan, according to Austin and Broome, is to expand what counts as a plan of care.

“The policy change that we’re working on right now is to expand that list of plans so that the last one on there is any other written plan of care,” Broome said. “So once the policy change goes into effect, you know if the (licensed clinical social worker) on staff does a clinical assessment and determines that this student has an anxiety disorder, based on clinical findings, we are going to treat this anxiety disorder. So I make a written plan of care to treat the anxiety disorder, and now I am providing services to that student to treat that anxiety disorder that will be billable hopefully next school year.”

If changes to North Carolina’s Medicaid plan are approved by CMS, district leaders said the training they’ve received from the collaborative has positioned them to take advantage of the increased flexibility and expand services to more students.

As the state is working to make it easier for districts to get reimbursed for school-based services, Broome said she is hearing a lot of uncertainty and misinformation around how federal Medicaid cuts from the 2025 budget reconciliation bill are going to impact schools. While these cuts could certainly influence overall Medicaid enrollment, Broome said the bill does not directly impact school-based Medicaid.

“H.R.1 (the 2025 budget reconciliation bill) is not directly cutting the school-based Medicaid program,” Broome said. “Even in North Carolina, even where you saw rate cuts already happen, those rate cuts did not affect the (local education agency) fee schedule, and I feel like I am almost at the point of going school to school saying, ‘Do not fire your staff. You do not need to fire your staff. Please keep your health care staff.’”

The future of the Medicaid Learning Collaborative

As to what’s next for the Medicaid Learning Collaborative, ROI said they do not currently have funding to extend the collaborative past this school year, although they are actively looking for it. Longer term, ROI staff described a vision where districts would build their own internal expertise and no longer need the cohort-based learning collaborative.

“Our dream is that we will not need a learning cohort anymore,” said La’Shanda Person, ROI’s Innovation Program Manager. “We want this to be something schools just know how to do.”

For districts looking to learn more about school-based Medicaid reimbursement, district leaders participating in the MLC recommend starting with the Medicaid Toolkit and reaching out to those districts who have participated in the MLC.

“Find a district that’s already doing it and try to meet with them,” said Crews. “We support a couple of our surrounding districts … We meet with them often and talk with them about how we got started, so that they can kind of get a jumpstart. Because there are things that we have figured out along the way that we would like to save our friends from having to learn.”

Finally, everyone EdNC spoke to emphasized that school-based Medicaid is just one piece of a larger system to support student mental health in schools. Austin emphasized the many other ways schools are supporting their students’ mental well-being from a multi-tiered system of support to Project AWARE to bullying prevention and character education.

“Medicaid is a part of an ecosystem,” said Broome. “It is not a single solution.”

Austin, Broome, and ROI are all hopeful that the lessons learned from the Medicaid Learning Collaborative can play a role in improving one part of the ecosystem of care for North Carolina’s students — a part that doesn’t disappear when grant money runs out.

Recommended reading