Mikki Sager is living proof that some people run on an extra gear. Last year alone she estimated she racked up some 70,000-odd miles just in rental cars doing her work as director of Resourceful Communities at the Conservation Fund. All of those miles have been on behalf of communities across North Carolina, and other parts of the South, which for too long have been marginalized and left out of the economic boons of the “new South.”

Sager has a seemingly encyclopedic knowledge of the back roads of the state, a deep network of everyday heroes doing remarkable work on behalf of their community, and she exudes the kind of energy that seems to come from those who work on behalf of others.

A few weeks ago Sager called and suggested I join her for a day traveling across Eastern North Carolina. I jumped at the opportunity, which is how I found myself standing out in the rain on a dreary Monday morning in an empty parking lot waiting for a sign of Sager in one of her trusty rental cars.

On a dreary Monday morning, I very much wanted to be at my desk catching up on emails instead of standing in the fog, but as soon as Sager showed up I realized how fortunate I was to be in her company for the day. As we headed out of Raleigh toward Henderson, Sager began to fill us in on the details of the folks that we were visiting first, and her warm introduction actually understated how amazing Artis and Henry Crews of the Green Rural Redevelopment Organization would turn out to be.

Henderson is a small town that has been left behind for some time, with the Great Recession only hammering their hopes further. As we pulled down the street leading to the offices of the nonprofit, we passed several homes that either were abandoned, or looked as if they should be.

We found our first stop at a small green house in front of a rain drenched garden. The neighborhood was quiet, foggy, and wet. Yet as soon as we parked, sunshine came out in the form of Artis Crews. Artis, the co-founder of the organization, bounded out of the door and passed out hugs all around, offered us coffee and sweet rolls as soon as we walked in, and proceeded to have us rolling with laughter immediately as she told the story of the formation of the nonprofit and all of the associated organizations. As she rattled off all that they had accomplished in a year and a half, we sat there stunned at the energy that had allowed a small garden to become a co-operative led by women, produce sold through Farmer Foodshare and at the Henderson farmers market, programming with local youth, several for-profit businesses, and even a member of the group being elected to City Council.

Artis laughed at our surprised faces as she delivered the quote of the day. “Honey, I’m 70-years old. I can’t slow down. That is coming soon enough.”

The day continued on to the Franklinton Center at Bricks, which was a former slave plantation that became one of the first accredited schools for African Americans in the South before becoming a hub for social justice rooted in religious faith before turning into a community hub today. The Franklinton Center is led by Vivian Lucas who manages a true community center, including a swimming pool with swim lessons, spaces that can be rented by a range of community groups, and a large garden, with only two other full-time staff members.

Before we arrived Sager said we would feel the history of the place in our bones. We were all moved by a site that commemorates the lives of those who were enslaved at Franklinton. Lucas told us that stories passed down through history included the possibility that the location was used to “break troublesome slaves,” which made it likely that men and women had died during that horrible time in Southern history.

Standing at that site as Lucas spoke of plans to make the place more entrepreneurial, with a beautiful backdrop despite the fog and misting rain, I could not help but consider the full arc of history. A history of progress, even as we have so far to go, which I was reminded of as we looked out at railroad tracks that divided Edgecombe and Nash Counties with Halifax County in the distance. Counties that have made progress, but still have contentious issues of race, poverty, and history weighing on them all.

Our final stop of the day was the Conetoe Family Life Center, which EdNC staff have visited numerous times since our launch earlier this year.

Conetoe’s story began with the vision of Reverend Richard Joyner who was tired of presiding over the funerals of young people who had died of preventable diseases. The vision became a garden, a summer program for youth, and now a full fledged organization that is transforming lives.

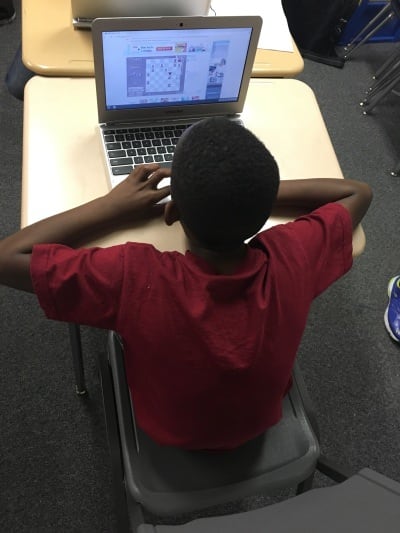

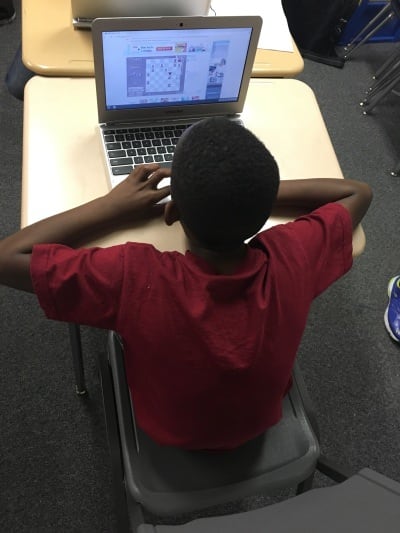

We pulled into the parking lot at the Conetoe Family Life Center at dusk. Yet the darkness outside was immediately surpassed by the energy and light inside of the prefabricated building that hosted the offices of the program, a seed room for the farm, and a dozen-plus children who were doing homework, learning how to play chess, and receiving mentoring from volunteers from the community.

It was clear that Conetoe is growing up. They are moving from a vision to a real, functioning program that is transforming lives beyond nutrition. They are not just building health, they are building the whole child, and in the process they are building the entire community.

Toward the end of our visit, Richard Joyner stormed through the doors. He encouraged the kids, checked in on staff, and caught Sager up on the activities in the area. I asked Joyner about becoming a CNN Hero for his work and he simply laughed. It is clear he was proud of the accomplishment for what it meant for Conetoe, yet he remains rooted in humility. “Look I’m up before sunrise on a tractor, I go work a full day, and then I come back to my community to try and make a difference.”

The biggest lesson from the day was that each of these communities, each of the leaders that we met, are rooted in humble beginnings, yet in their own way they are each working to provide hope to their broader community. And it might be that hope is the most important ingredient for the future of their community and the children who represent the future.