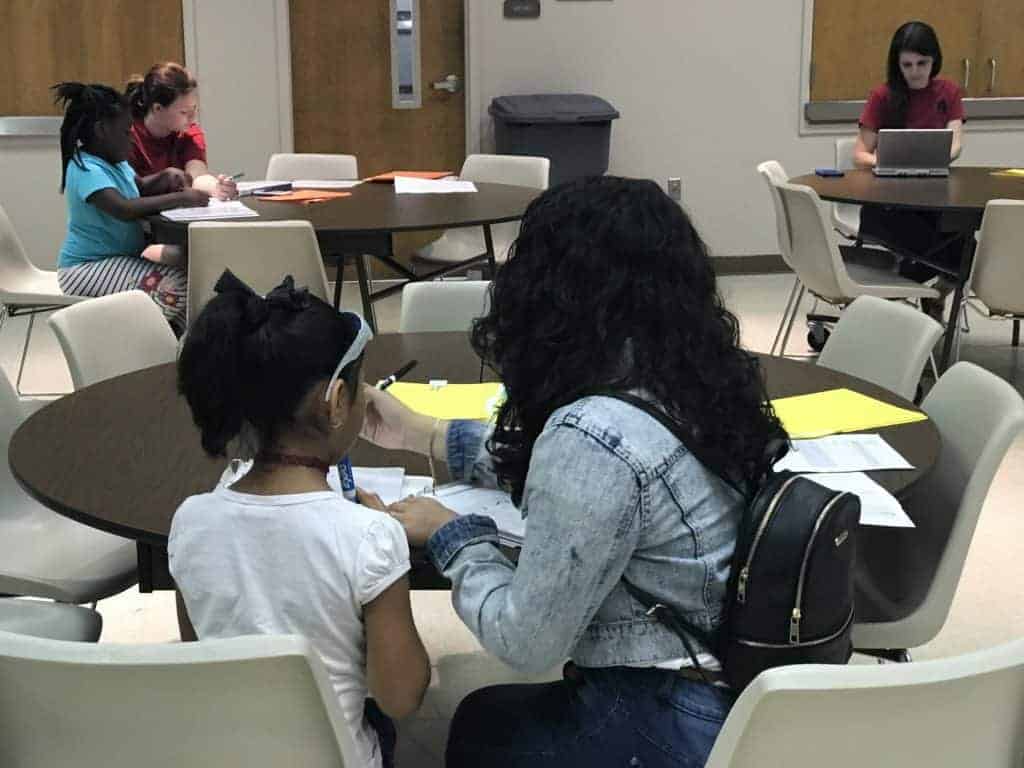

Round tables are clustered together at the back of a church fellowship hall in east Charlotte. At each table, a high school student in a red t-shirt huddles over a three-ring binder. Brightly colored folders are scattered across the surface. Seated next to each teenager is a student from Idlewild Elementary School, a Title I campus just down the road, ready to start a 15-minute reading exercise.

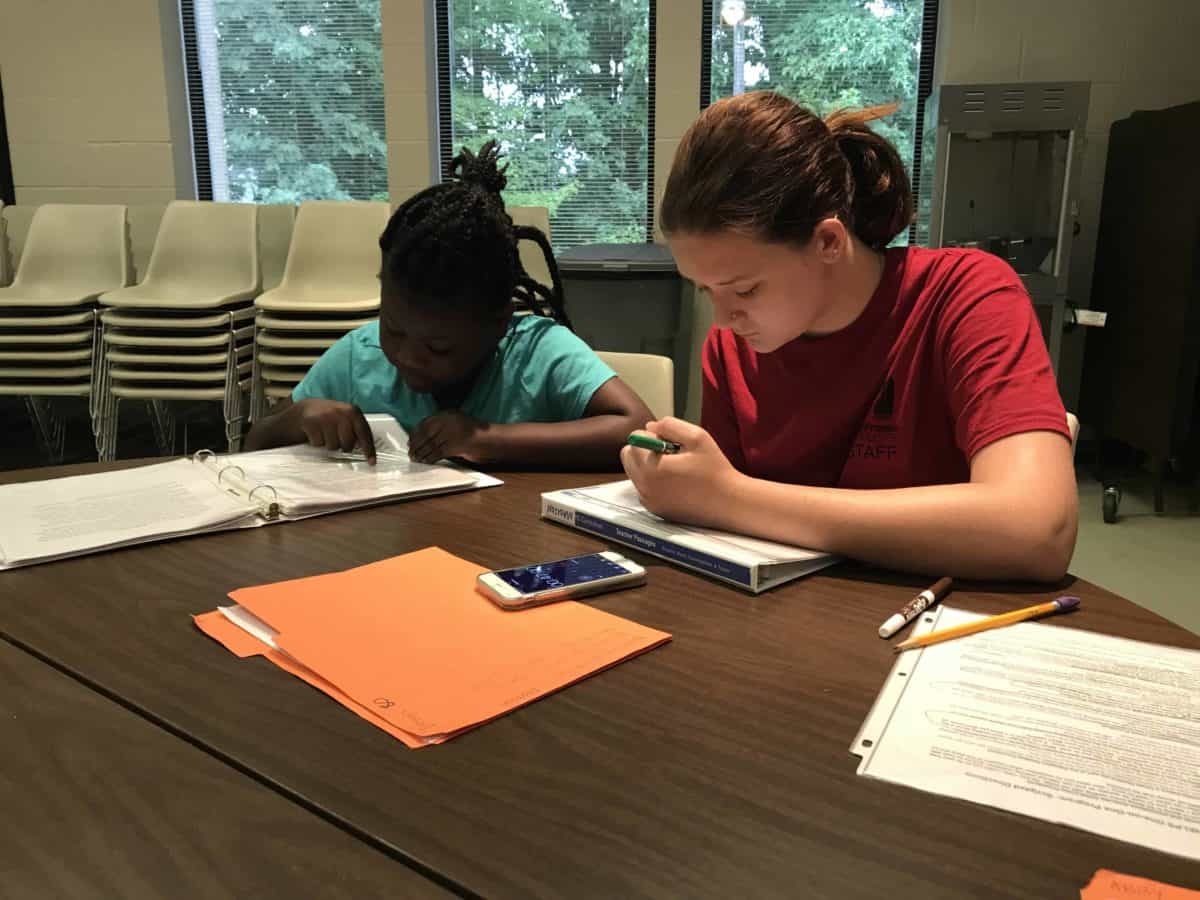

At one table, Desiya, an African-American girl with braids and an eager grin, starts to read a passage about exotic animals. She works her way through the words, stumbling here and there. Madison Taylor, a rising 11th-grader at Independence High School, carefully tracks Desiya’s performance on a separate sheet of paper, marking words that the young girl struggles to say.

“We just have four more to go,” Desiya says. “But I know this one.”

She stumbles over “three-hundred.”

“Can you say this word again?” Taylor asks as she points to it.

“Three-hundred,” Desiya says hesitantly.

“Three-hundred.”

“Three-hundred,” Desiya repeats—this time with authority.

Similar exchanges happen at the other tables—all part of the HELPS reading program during UrbanPromise Charlotte’s summer camp.

Focusing on fluency

The HELPS (Helping Early Literacy with Practice Strategies) program was founded by John Begeny, Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at NC State University, after recognizing the need for an evidence-based literacy program focused on fluency.

“There’s really not a lot out there to help teachers figure out what to do for reading fluency,” Begeny stated. “We know that with comprehension, vocabulary, phonics, and phonemic awareness, fluency is oftentimes neglected in the classroom.”

Munro Richardson, Executive Director of Read Charlotte, agrees: “People often refer to fluency as the forgotten literacy skill.”

Begeny spent years reviewing effective practices to increase reading fluency. He developed an approach that combines evidence-based practices with implementation science to create an effective, easy-to-implement program. Designed to be used just three times a week for 10-12 minutes per session, the one-on-one program fits easily in the school day.

During each session, the teacher (or tutor, volunteer, parent, etc.) models reading aloud from ability-appropriate passages and then listens and records as the student reads aloud the passage several times, correcting any errors and giving feedback and praise (see video below).

Begeny and Executive Director Elizabeth Levene stressed how important it is to couple evidence-based practices with a focus on implementation when developing programs for schools.

“The research to practice piece is crucial if we want to effectively and efficiently help students improve academically. The feasibility piece has to be there or it’s not going to happen,” Levene said.

“There are a lot of programs out there that are well-intended and have research supporting them, but there’s a wall between the really great program and the student. It can be anything from the time it takes, the type of person, or the level of training that person has to go through.”

“In a way there’s nothing super brilliant about any of it,” Begeny added. “It’s really thinking about the systems and figuring out the implementation science piece of it. How can we make it so that the front staff in the main office can do it, or a volunteer or speech pathologist, in a way that very easily all of those educators can be involved.”

Spreading HELPS across the globe

In addition to making it easy to implement, Begeny decided to make the HELPS program completely free for teachers to use.

“With my interest and focus on educational equity,” Begeny said, “I wanted to figure out a mechanism of making programs like HELPS and anything else we find to be effective truly free. Rather than buying it from a publishing company, you’ve got all the teachers manuals and training videos and all the materials you would need that you can download and print absolutely free.”

Begeny’s focus on implementation feasibility combined with making the program free to use has paid off. Because Begeny and Levene want to encourage as many educators to use the program as possible, they require hardly any reporting upfront from teachers. The downside is they can only estimate how many teachers are using it worldwide.

“I’ve guesstimated anywhere from 60,000 to 100,000 teachers [use the program], and that’s not just in the U.S.,” Begeny stated. “It would be fair to say that the program has probably come in contact with 100,000 kids.”

Seeing the results

When Munro Richardson first learned about HELPS, he was skeptical. However, as he reviewed the research and learned more about the program, he became convinced.

“I went to a training in October. I dragged my wife with me on a Saturday. I walked away really convinced that there was something here.”

According to Richardson, HELPS is ten times more effective than the average literacy intervention. In early 2016, his team did a review of the most promising literacy interventions. They surveyed 30 different databases and concluded that the typical intervention would lead to improved outcomes for three of every 100 students.

“We used that as a benchmark and said we want to see better than that,” Richardson said. “By comparison, for HELPS we would expect to see 35 out of 100 kids improved.”

When asked why he thinks the program has been so successful, Richardson said it’s a combination of three things: the research that went into developing it, Begeny’s dedication to educational equity, and its simplicity:

“The difference is John took the time to figure out what works. He wasn’t just trying to publish a research paper and move on. The second thing is because John was so serious about educational equity, he wasn’t trying to create something that he could sell to someone. He was trying to create something that could actually help children learn to read…[Finally], it is elegant in its simplicity. There are a lot of reading programs where if you look at what they’re trying to do, they are trying to address multiple skills at once. HELPS is focusing on one skill — fluency.”

Turning students into confident readers and leaders

Terri Buda taught for 16 years as her second career, seven in Texas and nine in Scotland County, North Carolina. For the last four years, she used the HELPS program in her second- and third-grade classrooms.

“I had never experienced growth like I did when I used HELPS in second grade,” she said. “When you have third-grade teachers who are fighting over the kids from your room, you know you’ve done something well.”

Part of what makes HELPS so successful, she believes, is that it boosts the students’ self-confidence.

“I think part of it is that the program really focuses on what kids can do as opposed to what they can’t do. I think it gives them a big boost in self-confidence, which low readers don’t normally have.”

After each session, the students visually chart their progress, setting a goal for their next session. After visiting UrbanPromise this summer, Richardson said he was surprised at how excited the kids are to do the program.

“Kids showed up at their next HELPS session excited and wanting to see if they can read more words per minute than they did last time. That was unexpected.”

“A lot of these kids are not on grade level, so they’re not getting many of those exciting moments at school,” said Christine Keitt, the literacy facilitator at the east Charlotte UrbanPromise site and a former CMS teacher.

At UrbanPromise, there are advantages for the tutors, too.

“They’ve really stepped up and taken ownership of the role. It’s really exciting for the kid and for the high schooler to see ‘Oh, what I’m doing is actually making a difference,’” Keitt said. “We’re trying to empower kids to become leaders in their communities.”

That’s one of the reasons Jairo Caicedo, a rising 11th-grader at Independence High School, decided to apply to be a literacy lead. “My leadership level at that time wasn’t as good as I wanted it to be,” he said in between sessions with students.

“Every time they improve, the kids get excited, they jump out of their seats, they get a little cheer on,” he said. That reaction—and the knowledge that he played a role in their success—has improved Caicedo’s own self-confidence. “My leadership level has gone dramatically up,” he said.

Other literacy leaders have a more personal connection to literacy instruction.

“Growing up, I struggled with reading,” said Erika Cruz-Bonilla, a rising 12th-grader at East Mecklenburg High School. “You have a fourth-grader and they’re reading at a first grade level, and they begin to feel ashamed of that. Kids start teasing them.”

“I remember how that felt.”

Cruz-Bonilla, who started CMS in the English as a Second Language program, now leads the HELPS high school team. She said her own experience created the passion to help other kids who struggle with reading.

“I know how hard it can be to not be reading on level, and how you start feeling that shame,” she said. “Sometimes you think that they don’t notice, but they do. They really do know that they’re not on level, so they’re always pushing themselves.”

Even after a few weeks of the program, she’s noticed a difference in the students she serves.

“I have kids who were at a second grade level and now they’re at a fourth grade level,” Cruz-Bonilla says. “It warms up your heart.”