The Republican-controlled General Assembly has overridden eight of Democratic Gov. Josh Stein’s 15 vetoes since taking office in January. The power to override the veto allows Republicans to reshape public policy, placing a spotlight on the rules and procedures behind the state’s veto power.

Republicans have a veto-proof majority — or a supermajority — in the Senate. While Republicans in the House lost their supermajority by one vote, House Speaker Destin Hall says the GOP operates as if it has a supermajority, calling it a “working supermajority for all intents and purposes” just after the November 2024 elections — dependent on just one Democrat joining Republicans to override the governor’s veto.

Those overrides are impacting education issues, including guns for private school staff and school vouchers.

Though Republicans have successfully overridden most of Stein’s vetoes so far, shows of unity from the N.C. Legislative Black Caucus suggest the GOP might have a harder time trying to override vetoes on three anti-DEI bills.

The history of the veto in North Carolina

In 1996, North Carolina became the last state in the nation to give its governor the veto power. The power came through a constitutional amendment approved by 75% of North Carolina voters.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

But before the measure made its way onto the ballot, state legislators had to pass Senate Bill 3 in 1995. That legislation was authored by none other than then-state senator Roy Cooper — who would go on to become governor and the current Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate.

Veto power for the governor was a key issue for then Republican Gov. Jim Martin. Cooper garnered widespread bipartisan support for his bill through a few compromise measures, including lower override thresholds, according to a report by The Assembly.

At the time, the arguments for the veto included:

Veto power was needed in order to make the governor a full partner in the legislative process;

Veto power could serve as a check against passage of legislation which has been rushed through the General Assembly without full deliberation or which is not in the public interest;

It could be used to negate unconstitutional legislation;

It could restore a proper balance of power between the executive and legislative branches; and

It had worked well in practice at the federal level and in all other states.

— The N.C. Center for Public Policy Research

The low-override threshold has given Republicans the opportunity to strike down the governor’s vetoes eight times this year — with more expected to come when legislators return to Raleigh in September. Here is how veto power has played out historically since 1997.

How does veto power work in North Carolina?

A veto is defined by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) as “1) the power vested in a chief executive to disapprove the enactment of measures passed by a legislature, or 2) the message that usually is sent to the legislative assembly by the executive officer, stating the refusal to sign a bill into law and the reasons therefor.”

In short, a veto allows the governor to reject measures passed by the state legislature.

The NCSL lists four types of vetoes:

- Regular veto | The power to reject a full bill passed by a legislature.

- Amendatory veto | The authority to return a bill to the legislature with recommendations for changes.

- Reduction veto | The ability to reduce the amount of spending on a bill’s specific line item without rejecting the full amount.

- Line-item veto | The power to reject specific provisions within a bill, while approving the rest of it.

North Carolina’s governor doesn’t have all those powers, though. The constitutional amendment gave the governor one of the weakest veto powers in the nation.

The governor has no line-item veto power and holds no authority over redistricting, constitutional amendments, resolutions passed by the General Assembly, or bills that apply to 15 or fewer counties.

Another veto type is the pocket veto — when the executive power, simply put, does nothing. In these cases, the president or a governor declines to sign a bill into law within a certain time frame, thus killing the bill. According to the NCSL, at least 11 state governors have such power.

But in North Carolina, the opposite is true.

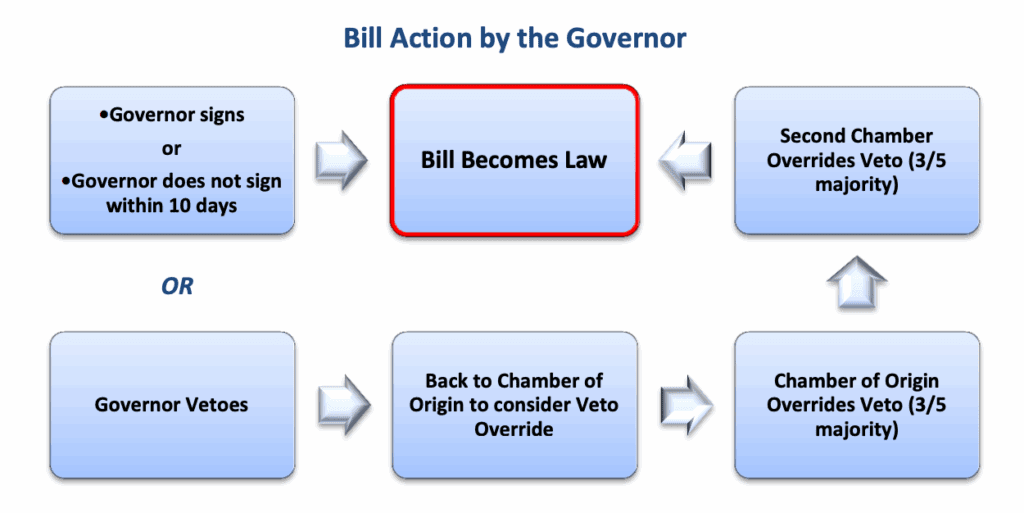

When the legislature is in session, the governor has 10 days to sign or veto the bill. If the governor doesn’t do either, the bill becomes law without his signature. If the legislature has adjourned indefinitely or for more than 30 days, the governor gets 30 days to make a decision from the day the adjournment begins. If the governor doesn’t take action during those 30 days, the bill becomes law.

The legislature can schedule a vote to override a veto at any point during that year’s legislative session.

Related reads

How do veto overrides work?

Beyond those limits to the veto power, overriding the governor’s veto is also easier than in other states.

In 36 states, overriding a governor’s veto requires a two-thirds vote from the legislature. Six require a simple majority vote. In Alaska, the state’s chambers gather as a unicameral body for a joint session, and two-thirds must vote to override. Seven states require a three-fifths vote. (These thresholds sometimes differ depending on the type of bill according to the NCSL.)

North Carolina is one of the country’s seven states requiring a three-fifths vote.

Once the governor issues a veto, the bill returns to the chamber where it originated. If three-fifths vote to override the veto, the bill goes to the second chamber. If three-fifths of the second chamber override the veto, the bill becomes law.

Running the numbers

Since veto overrides require three-fifths of both chambers, assuming all members are in attendance to vote, an override requires 72 representatives and 30 senators.

Following the November 2024 election, the state House of Representatives has 71 Republicans and 49 Democrats. The state Senate has 30 Republicans and 20 Democrats.

With these numbers, Republicans have a veto-proof majority — or a supermajority — in the Senate, and are one vote shy of a supermajority in the House.

The legislature had the same split after the 2022 elections. However, when Rep. Tricia Cotham, R-Mecklenburg, left the Democratic Party to join state Republicans in the spring of 2023, she gave her new party the 72 seats needed for a supermajority. The move impacted the power of then-Gov. Cooper, whose vetoes were consistently overridden after Cotham’s switch.

2025 overrides

Since taking office in January, Stein has vetoed 15 bills. In late July and August, Republicans were able to override eight of Stein’s vetoes with the support of defecting Democrats.

Among those bills, which have since become law, are three education-related pieces of legislation: House Bill 805, Senate Bill 254, House Bill 193. Stein also vetoed House Bill 87, which would enroll North Carolina in a federal school choice program, but lawmakers have not yet overridden that veto.

House Bill 805

House Bill 805 began as a measure requiring pornographic websites to obtain consent, giving individuals depicted in explicit photos or videos the right to have the material taken down. But in the Senate, lawmakers expanded the bill far beyond its original scope. The final version of the law allows lawsuits against medical providers involved in gender transitions and requires transgender people’s birth certificates to attach the original certificate with their sex at birth.

The bill also instructs schools to create a “searchable web-based catalog” of all available library books. Parents or guardians will then be allowed to identify books that their child shall not be allowed to check out from the library.

Republicans were able to override Stein’s veto thanks to the support of Rep. Nasif Majeed, D-Mecklenburg, the single Democrat who joined their ranks for the vote.

“I’ll put it in a blanket situation: There were some moral issues in there that I had some sentiments, some deep sentiments about it. So that’s why I support it,” Majeed told NC Newsroom in an interview.

Senate Bill 254

Senate Bill 254 amends charter school laws. The law restricts the State Board of Education’s authority over these schools and requires that all rules or policies impacting them be approved first by the Charter Schools Review Board.

In his veto, Stein described the bill as “an unconstitutional infringement on the authority of the State Board of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction,” which would weaken charter schools’ accountability.

A statement from the State Board Chair Eric Davis and State Superintendent Mo Green described the leaders’ concern over the bill’s provisions.

“Charter schools are public schools. Several provisions in Senate Bill 254 unconstitutionally propose to transfer core responsibilities of oversight, accountability and rulemaking for charter schools from the North Carolina State Board of Education (SBE) and North Carolina Superintendent of Public Instruction … to a non-constitutional body, the CSRB,” the statement read.

In a statement issued after the vote to override Stein’s veto, Dave Machado, executive director of the North Carolina Coalition for Charter Schools, thanked the legislators who voted in favor of the override.

“Public charter schools succeed because of their flexibility and autonomy. Senate Bill 254 protects that flexibility and autonomy by empowering a body of charter school experts, insulated from political maneuverings, at the front line of regulation and oversight,” Machado said.

Eight Democrats voted in favor of the original bill and three approved the override of Stein’s veto.

Read more

House Bill 193

House Bill 193 includes a provision allowing private school administrators to authorize trained volunteers and staff to carry concealed weapons on school property.

Stein’s veto said the bill would make children less safe. He said guns should be kept out of schools unless they are in the possession of law enforcement. His statement also mentioned an incident at Faith Christian Academy in Goldsboro in February of last year, when an elementary school student found an employee’s gun that had been left in a bathroom.

Rep. Shelly Willingham, D-Edgecombe, joined Republicans to override Stein’s veto. In an interview with WUNC, he said private schools are “small enough that staff could safely have weapons to protect their students.”

Willingham has sided with Republicans to override six of Stein’s vetoes. An August report from WRAL said he intends to help them override at least one veto on another piece of education legislation, House Bill 87.

House Bill 87

House Bill 87 would opt North Carolina into the federal school voucher program in President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans’ federal budget bill.

The legislation allows “any taxpayer to receive a federal tax credit equal to the amount of their charitable contributions to qualifying scholarship granting organizations, up to $1,700” starting in 2027.

Scholarship granting organizations are nonprofits who fund and oversee the distribution of scholarships for K-12 students. That can include scholarships for private school tuition, virtually creating a tax credit for individuals funding private school vouchers.

“Cutting public education funding by billions of dollars while providing billions in tax giveaways to wealthy parents already sending their kids to private schools is the wrong choice,” Stein said in his veto.

Still, Stein said he would eventually commit the state to the federal program, using the funds to support the state’s public schools.

“Once the federal government issues sound guidance, I intend to opt North Carolina in so we can invest in the public school students most in need of after school programs, tutoring, and other resources,” Stein wrote in his veto message. “Therefore, HB 87 is unnecessary, and I veto it.”

Read more

Other vetoes

In addition to these three education bills, Republicans have overridden Stein’s vetoes on five other bills:

- Senate Bill 416, Personal Privacy Protection Act;

- Senate Bill 266, The Power Bill Reduction Act;

- House Bill 402, Limit Rules With Substantial Financial Costs;

- House Bill 318, The Criminal Illegal Alien Enforcement Act; and

- House Bill 549, Clarify Powers of State Auditor.

The vetoed bills that Republicans have not yet overridden include Senate Bill 50, Freedom to Carry NC; Senate Bill 153, North Carolina Border Protection Act; and House Bill 96, Expedited Removal of Unauthorized Persons; as well as three anti-DEI bills.

Anti-DEI bills

Willingham’s comments in favor of overriding Stein’s veto have put him — and state Democrats — under scrutiny. When asked about the party’s unity, North Carolina Democratic Party Chair Anderson Clayton told WRAL that voters had given Stein the veto power.

“Any legislator who chooses to deny that power is betraying the will of the people. We will be watching,” Clayton told WRAL.

The three anti-DEI bills — House Bill 171, Senate Bill 227, and Senate Bill 558 — address diversity, equity, and inclusion in state government and education institutions.

The Senate already voted to override Stein’s veto on Senate Bill 227 and Senate Bill 558; the bills must now move to the House for a vote to override. Legislators have not yet voted to override House Bill 171.

However, all 41 members of the Black Caucus agreed to uphold the vetoes, according to a statement released on Aug. 26. Among these members are frequent Democratic swing voters — including Willingham and Majeed, who already sided with Republicans to override at least one of Stein’s vetoes.

“If enacted, these bills would tear down the programs and policies that help create equitable opportunities in schools, workplaces and state agencies,” the statement said. “They would send a message to every Black North Carolinian and community of color that their voices, experiences and futures do not matter.”

The General Assembly is scheduled to reconvene from Sept. 22-25, according to its July adjournment resolution.

Recommended reading